Part 1 of Civic Theology: How the Bible Shaped America’s Founding and Freedom

In a season of fierce political debate and cultural fracturing, many believers feel torn: should Christians retreat into spiritual bunkers (pietism) or seize state power (theocracy)? Civic theology offers a different path. It is the biblical vision that God cares about our cities, laws, and leaders – and calls His people to pray, vote, and serve the common good without demanding a Christian empire. Civic theology neither dreams of a church-controlled state nor shrugs off society. Instead, it urges Christians to live as salt and light, working “for the welfare of the city” (Jer. 29:7, ESV), while giving Caesar and God their due (Matt. 22:21) .

Civic theology is not theocracy, Christian nationalism, or pietism. To be clear:

- Not Theocracy: It does not call for clerics to rule by divine right or for civil law to become church law. In America, church and state are constitutionally separate (First Amendment) – believers support just laws without demanding an official state religion . We respect governmental authority (Rom. 13:1–7) but do not confuse patriotic duty with a mission to impose Christianity by force .

- Not Christian Nationalism: It is not a narrow nationalism that fuses patriotism with a single faith. Civic theology gladly prays for our nation’s well-being (Jer. 29:7) yet remembers that ultimate allegiance is to “Christ as Lord” (Col. 3:17). We celebrate America’s heritage without idolizing the flag – we are citizens of heaven first .

- Not Retreating Pietism: It does not ask Christians to “sit out” public life in monasteries or deny love of country. Our faith should overflow into how we vote, work, and love neighbors. As one midwestern pastor quips, “I can’t tell Washington what to do from my pew – but I can pray for it” . Civic theology lifts the gospel from pew to public square, engaging culture without being consumed by it.

Put simply, civic theology is the doctrine that Jesus cares how we live in the world He created. It answers the question, “How does Christ want Christians to act in the public arena?” It says our faith isn’t boxed into temples or home groups; it shapes our taxes, town councils, and how we treat the homeless. True civic theology says: “Our call is to be the best citizens we can be – honest, generous, truth-speaking – because God’s kingdom principles are true at every level of life” . It assumes God is sovereign over all (Dan. 4:17), including the authority figures we’re “subject to” (Rom. 13:1). This faith-filled engagement is a far cry from a cynical secular politics or a church takeover; it’s a middle way: obedient citizens, faithful ambassadors for Christ.

Biblical Foundations of Civic Theology

The Bible repeatedly shows that God cares about civil life and calls His people into it. For example, Jeremiah 29:7commands exiles in Babylon to “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you… and pray to the LORD on its behalf; for in its welfare you will have welfare.” This surprises some believers: even in exile, God told Israel to work for Babylon’s peace! The principle is clear for Christians: we don’t denounce our hometowns from afar, we love them (seek justice, peace, and prosperity) as part of our obedience .

Similarly, Romans 13:1–7 teaches respect for authority. Paul bluntly says, “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except from God” (Rom. 13:1) . This doesn’t mean blind obedience (tyrants abuse power), but that government itself is God’s common grace to restrain evil. Paul even orders taxes be paid and honors given, because rulers are God’s servants (Rom. 13:6–7) . Civic theology takes Romans 13 seriously: Christians obey laws, pray for rulers (1 Tim. 2:1–2), and recognize that God places leaders “for our good” (John 19:11).

Christ Himself modeled civic wisdom. When asked about taxes, Jesus said “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matt. 22:21) . He neither called for revolution (theocracy) nor abdicated all civic duty (pietism). Instead, He drew a line: pay taxes, vote, serve, but remember your ultimate King is God. And when Pilate tried to make Him a political threat, Jesus answered, “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36) – showing He won’t play party-politics for power. Civic theology honors that balance: it is worldly-minded enough to say “yes, vote and serve” but Godward-minded enough to say “yes, worship and pray.”

Even praise of a nation traces to Scripture. Psalm 33:12 exults, “Blessed is the nation whose God is the LORD, the people he chose for his own inheritance!” . This isn’t a KJV-only prooftext for nationalism, but it does show Scripture’s view that God’s blessing extends to political communities when they follow Him. Christians of all eras have taken this to heart: we thank God for our country’s freedoms, even as we grapple with its sins. Civic theology prays that our land might be blessed (Micah 6:8) – knowing that when a nation honors justice and righteousness, it flourishes under God’s favor .

From Old Testament judges to New Testament apostles, the Bible never whispers “God’s kingdom only” as an excuse to ignore society’s problems. On the contrary, God commands loving our neighbors by feeding the hungry, aiding the widow, shunning corruption – tasks that often involve civic engagement. Jeremiah’s commanding us to “pray for peace” and Paul’s urging “respect the emperor” teach that godliness includes public responsibility . In sum, Scripture grounds civic theology: we live in two kingdoms (see Acts 5:29 vs. Rom. 13:1) but under one God. We obey rulers (Matthew 22) and honor God (Psalm 33) in the same breath. This tension is the heart of civic faith.

Civic Theology in Contrast:

Not Theocracy, Not Nationalism, Not Pietism

To clarify what civic theology is, it helps to say what it is not. In short, civic theology rejects three common pitfalls:

- Theocracy (God’s Law by State Force): America’s founders abhorred a state church, so civic theology does too. We reject any attempt to force Scripture as civil law. Romans 13 tells Christians to obey existing authority, not to throw out secular law and install church rule. Jesus’ “Render to Caesar” means we pay taxes and serve, but we don’t chase clerical crowns . The Puritan colonists of New England sought godly governance (covenants, moral codes) – but even they debated how far civil magistrates should enforce church discipline. Civic theology follows Jesus’ lead: it ministers to the heart through civil society, but it keeps the Church and the State in their lanes. Government is an earthly stewardship (Gen. 9:6, Rom. 13), not the Bride of Christ, and we honor that boundary.

- Christian Nationalism (Idolatrous Patriotism): Christian nationalism claims a particular nation (the “godly” one) is chosen above others, with political leaders acting as God’s anointed agents. Civic theology balks at this. We love America, but we love justice more. Our citizenship is first in heaven (Phil. 3:20), not in any earthly capital. We serve our neighbors regardless of party, race, or even country, because the Great Commission is global. Yes, we thank God for liberty and recognize Christian heritage in our laws – but we don’t confuse Christian symbols for the gospel. If national pride swallows Jesus, then we’ve missed the point of Christ’s kingdom. Civic theology stands for human rights and moral truth no matter who holds power. It encourages voting and service, but guards against waving the flag more than the cross. As Tocqueville warned, religious fervor can be twisted into a civil “religion of the majority” – civic theology rejects that trap . We submit patriotic duties to God’s higher law (Acts 5:29).

- Detachment or Pietism (“Don’t Rock the Boat”): On the opposite end, some Christians say politics is “filthy” and we should stick to sermons and soup kitchens. That’s not biblical either. Civic theology says the gospel impels us into the world: speaking truth to power, showing mercy in the marketplace, working for injustice. If Christ is Lord of all life, His Lordship doesn’t stop at the sanctuary doors. Civic theology won’t tolerate Christians acting as moral hermits while evil flourishes (James 2:14-17). We do not “pass through on the other side” whenever our neighbors need justice or our country asks for service. We pray, of course – but we also vote, debate, and sometimes picket. John the Baptist told soldiers, “Do no extortion” (Luke 3:14); the New Testament includes instructions to rulers and tax collectors alike. Civic theology happily engages government, cultural institutions, and civic life as venues for Christian witness, believing God can use our influence for good.

In sum, civic theology is “All of life for Christ” extended to our public life. We do not bow to the state like patriots (Rom. 13), nor do we bow out and become spectators. We live faithfully in both realms: praying for leaders (1 Tim. 2:1–2) and urging them toward justice, as Jeremiah urged the exiles to work for Babylon’s peace . We honor God’s ordinances (parents, employers, voters) while giving Him glorious praise. This balance is the heart of civic faith – a refusal to split kingdom loyalties or shut God out of politics.

Historical Insights:

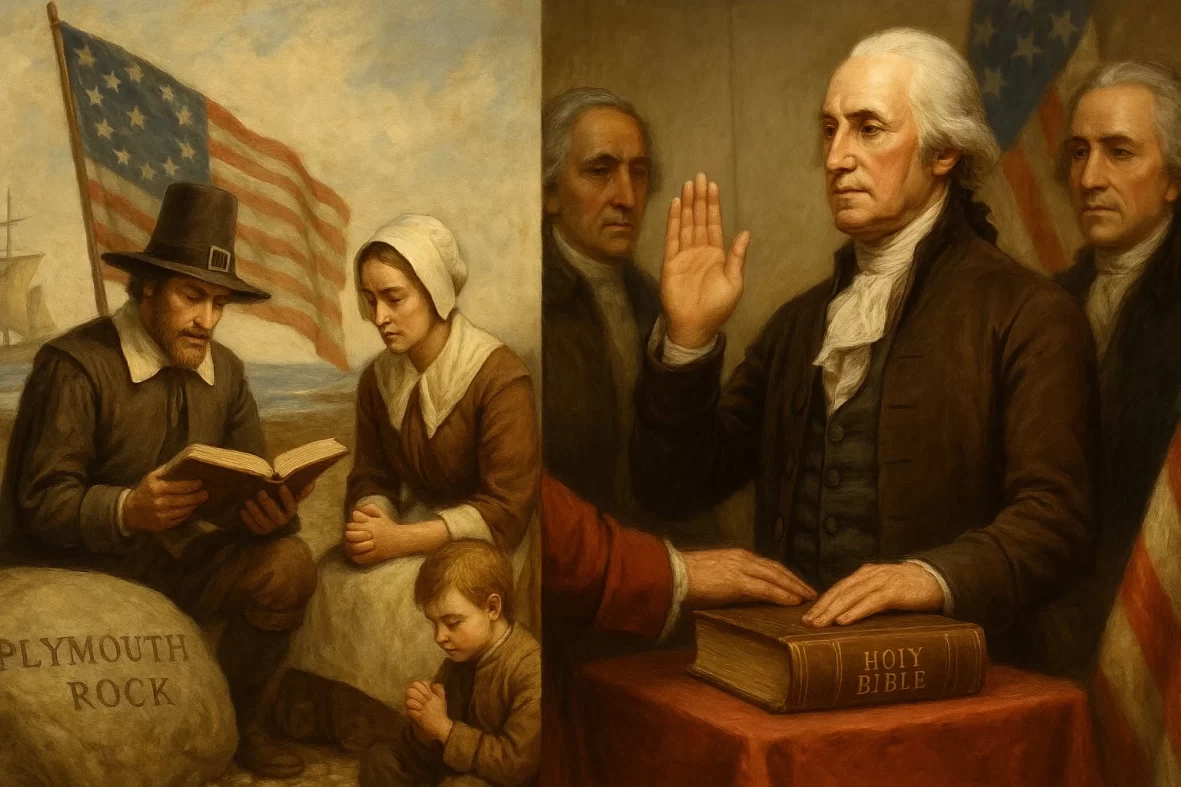

Puritans, Founders, and Tocqueville

Civic theology isn’t a modern invention; it has deep roots in American history. Long before 1776, Christian communities saw their civic life through biblical eyes. The Puritans of New England (1620s–1700s) famously spoke of a “covenant” with God in establishing a society. John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, described the colonists aboard the Arbella (1630) as having “entered into covenant with Him for this work… we have taken out a commission” . In other words, their new society was founded on a promise to obey God. Winthrop insisted the community “follow the counsel of Micah: to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with [God]” (Micah 6:8) . He even prophesied that Massachusetts would be “as a city upon a hill” – not in a nationalism sense, but meaning everyone would watch this little society to see if Christians could truly live out biblical justice and love .

Winthrop’s ideals – binding church and society together in a moral commonwealth – certainly veered close to theocracy. In practice, Puritan laws often reflected Old Testament sanctions (on Sabbath-breaking, blasphemy, etc.) . But they also innovated ideas of liberty: Winthrop contrasted natural liberty (doing whatever one wants) with civil liberty (the right to do what is just and good under God’s law) . Their lesson: freedom means obedience to God-given order, not license. The Pilgrims on the Mayflower likewise wrote that famous pact “in the name of God” to form a “civil body politic… for our better ordering and preservation” . These early Christians shaped America’s first constitution (the Mayflower Compact) around a biblical vision of covenant community.

By 1776, Americans had mixed religious influences: Puritan-covenant thinkers, Enlightenment philosophers, and evangelical revivals alike. The Founders generally rejected theocracies – they famously wrote “no religious Test” into the Constitution. But they strongly agreed on a point: religion undergirds republics. George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address echoes Puritan language: “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports” . He warned candidly, “national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle” only at the country’s peril . Adams, Jefferson, Madison – they all assumed that without faith, liberty would wither. As John Adams said, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Many early statesmen called Americans to prayer for the nation (e.g. Franklin asked God’s help at the Constitutional Convention ). Even Charles Carroll, the Catholic signer, believed “without morals a republic cannot subsist” and that attacking Christianity was undermining America’s foundations .

These founders formed what Tocqueville later called a “civil religion” – rituals and language that invoke God without preferring a single church. The Pledge of Allegiance (“Under God”), “In God We Trust” on money, and the 1787 Constitutional phrase “Providence” all reflect this. They frame America as blessed by God if she follows just principles, but never as a “Christian nation” in a theocratic sense. Civic theology today looks much like this: it honors America’s Christian heritage (Psalm 33:12) while upholding freedom of conscience (First Amendment).

By the 1830s Alexis de Tocqueville traveled our young nation and took note. He marveled that American democracy and Christianity marched hand-in-hand. He observed that Americans “bring their religion with them into public affairs” even as they avoid a formal state church . For Tocqueville, America’s Puritan roots had taught us the hard lesson that freedom needs faith: religion supplies the moral habits (truthfulness, self-sacrifice, love of neighbor) which democracy cannot enforce by law . He famously wrote that religion in America should be considered “the first” of our political institutions and that preserving it was essential to liberty . In short, our civic life was always meant to be religiously shaped, even if indirectly.

Tocqueville saw the paradox: democracy tends to make people self-centered and reliant on the majority, which can erode tradition and even faith . But Christian churches counterbalance this, teaching men that they are brothers under God. He concluded that if Americans gave up that religious balance, their free institutions could not last. Tocqueville’s insight still challenges us today: when morality drifts from Christian roots, civic trust erodes. Civic theology answers his warning by urging Christians to keep faith visible and active in the public square, not through slogans, but through habits of neighborly love and justice.

Civic Theology in Action:

Why It Matters Today

Civic theology is not just historical curiosity – it’s urgently relevant now. Our country is polarized, our culture debates moral issues, and many Christians wonder how to respond. Civic theology offers a framework: be in the world, not of it, engaging issues with biblical wisdom. It means voting prayerfully, serving in community boards with humility, and speaking truth with grace. It acknowledges both the good (freedom of religion, dignity of human life) and the bad (racism, violence, injustice) in our civic life. Because Jeremiah 29:7 taught us to work for city peace, we support schools, neighborhoods, police reforms, taxes for the needy, all while proclaiming God’s Word. Because Romans 13 taught obedience, we don’t applaud anarchy – but because Micah 6:8 calls justice, we boldly confront oppression.

Just as the early church navigated pagan Rome without ceding its faith, Christians in a plural democracy can hold fast to God’s unchanging truth while loving fellow citizens. “Civic theology” reminds us that owning a Bible goes with a citizen’s handbook: speak for the unborn, forgive 7×70, build bridges across divides. It rebukes idolizing politicians (no Caesar can save), and it also rebukes political quietism (your Caesar maybe can save lives). It’s the high calling to be faithful first, but not absent from public life.

Ultimately, civic theology trusts in God’s sovereignty over nations (Dan. 2:21): He “changes times and seasons” (Dan. 2:21) by raising up presidents or protests, and we pray into that. It means attending to Sunday worship and Monday’s city council with the same kingdom lens. As Psalm 33:12 promises, when a nation’s God truly is Lord over it, its people can hope for prosperity . Civic theology is simply living out that hope – in our churches, classrooms, and capitols – without fear or compromise.

In the words of an 18th-century preacher at a public election sermon: “To the kindly influence of Christianity we owe…the degree of civil freedom and happiness which mankind now enjoys… whenever the pillars of Christianity are overthrown, our government and blessings must fall with them.” Civic theology hears that warning and answers, “Then let us rebuild those pillars!” Not by conquest of the state, but by Christian witness in it.

This post is just the prologue. In the coming series “Civic Theology: How the Bible Shaped America’s Founding and Freedom,” we will dive into the founding documents, the lives of key leaders, and the laws they made – all through the lens of Scripture. We’ll see again and again how the Bible’s vision shaped our Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and public schools, and how it calls each generation to live faithfully as Americans. May the Lord bless our reading and our republic alike, as we seek the good of our cities in His name (Jer. 29:7; Rom. 13:1–7; Matt. 22:21; Ps. 33:12) .

References

Elazar, D. J. (n.d.). Covenant and the American founding. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved from https://dje.jcpa.org/articles/cov-amer.htm

Hall, M. D. (2020, October 23). Faithful citizenship: The founders on religion and the republic. Religion & Liberty, 30(4). Acton Institute. Retrieved from https://www.acton.org/religion-liberty/volume-30-number-4/faithful-citizenship-founders-religion-and-republic

Holloway, C. W. (2016, March 7). Tocqueville on Christianity and American Democracy. Heritage Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org/civil-society/report/tocqueville-christianity-and-american-democracy

Smith, S. M., Tucker, E. D., & Tucker, D. (2009). A model of Christian charity (John Winthrop, 1630). TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved from https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/a-model-of-christian-charity/

Winthrop, J. (1630). A model of Christian charity (boarding the Arbella, Dec. 11, 1630) . In S. M. Smith, E. D. Tucker, & D. Tucker (Eds.), Teaching American History. Retrieved from TeachingAmericanHistory.org (Original work published 1630)

Washington, G. (1796). Farewell Address . In M. D. Hall (Ed.), Religion & Liberty (pp. 2–7). Acton Institute. Retrieved from https://www.acton.org/sites/default/files/images/legacy/pub/pdf/farewell_address.pdf (Original address, Sept. 19, 1796)

Adams, J. (1798). Letter to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts. (Later cited in Hall, 2020) .

Bible. (n.d.). English Standard Version (ESV) (Jeremiah 29:7; Romans 13:1–7; Matthew 22:21; Psalm 33:12). Crossway Bibles. Retrieved from https://www.biblegateway.com (Scripture quotations are from the ESV).

Want to explore further?

Dig Deeper into Civic Theology