Why rare law-enforcement actions feel unprecedented—and how history helps us understand them

Why This Moment Feels So Disorienting

One of the most valuable things I learned as a recent graduate of the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University was not a policy position or a partisan framework, but a discipline of thinking. Again and again, we were trained to slow down, to separate emotion from analysis, to distinguish facts from reactions, and to classify problems before trying to solve them. The rule was simple, but demanding: logic before emotion, evidence before instinct.

That habit matters most in moments like this.

When events feel shocking or unprecedented, the pressure to react is immediate. Headlines race ahead of context. Commentary outpaces comprehension. Moral judgments form before basic categories are established. In those moments, public discourse tends to polarize quickly, not because people are malicious, but because emotion fills the vacuum left by understanding.

The recent events surrounding Venezuela and the capture of Nicolás Maduro have landed squarely in that kind of moment. The coverage has been intense, often breathless, and frequently framed as something without parallel. For many readers, the sheer force of the headlines creates a sense that the normal rules of law, history, and precedent have been suspended, replaced by raw power or political impulse.

This article is not written to defend any person, administration, or policy. It is not an argument about guilt or innocence, nor an endorsement of charges that will ultimately be weighed in court. Those questions matter, but they are not the first questions.

The first question is simpler and more foundational: what kind of event is this?

That question is often skipped in public conversation, but it is the one history insists we ask. Classification precedes evaluation. Understanding must come before judgment. Without that order, even well-intended analysis becomes distorted.

What follows is an attempt to apply that discipline of thinking to a confusing and emotionally charged moment. We will lay out what actually happened using careful terminology. We will examine whether this event fits within a recognizable historical pattern, drawing on primary legal and historical sources rather than contemporary commentary. And we will look honestly at where mainstream media coverage tends to break down when rare but recurring patterns reappear.

This is not an exercise in minimizing the seriousness of what has occurred. Rare events are often serious precisely because they are rare. But rarity is not the same thing as novelty, and shock is not the same thing as historical uniqueness. History is full of moments that felt unprecedented in real time and familiar in retrospect.

A biblical worldview reinforces this posture of restraint and clarity. Scripture consistently warns against answering before understanding and against bearing false witness through haste or exaggeration. Wisdom, both in personal life and public life, begins with careful hearing, patient reasoning, and truth told plainly.

In that spirit, the goal here is modest but important: not to settle the debate, but to steady it. To move from reaction to reasoning. To let history do what it does best when we allow it to speak: remind us that even in moments of disruption, patterns still exist, and discernment still matters.

Only once we understand the category of event we are dealing with can we begin to discuss its consequences responsibly.

What Actually Happened

A Factual Timeline, Without Commentary

Before examining historical patterns or media framing, it is necessary to establish a shared factual baseline. Confusion often enters public debate not because facts are unavailable, but because they are presented out of sequence, blended with interpretation, or described using imprecise language. This section is intentionally narrow. It focuses on what happened, how it happened, and the legal terminology involved, without evaluating motives, legitimacy, or outcomes.

Pre-existing criminal charges

Years before the events now dominating headlines, the United States Department of Justice filed criminal indictments in federal court against Nicolás Maduro and several senior Venezuelan officials. These indictments alleged violations of U.S. criminal law, including drug trafficking–related offenses. The charges were unsealed publicly and remained active. No new emergency charges were created at the moment of capture. The legal posture was established in advance.

From a procedural standpoint, this matters. In U.S. criminal law, an indictment signals that a grand jury has found probable cause to believe crimes were committed and that the accused should be brought before the court. It does not establish guilt, but it does establish jurisdictional intent.

Fugitive status under U.S. law

Because the indictments remained unresolved and the accused individuals were outside U.S. custody, they were classified by U.S. authorities as wanted persons. In domestic legal terms, this status is often described as “fugitive,” meaning an individual under active indictment who has not submitted to the court’s jurisdiction.

It is important to note what this designation does and does not mean. It is a term of domestic law, not international law. It does not confer authority to operate inside another sovereign state. It simply describes the procedural posture of a case within the U.S. legal system.

The absence of extradition

Extradition is the standard mechanism by which one state requests that another state arrest and surrender an individual for prosecution. It requires a treaty framework and the consent of the territorial state. In this case, extradition was not a viable pathway. There was no cooperative extradition process in operation between the United States and Venezuela that could realistically produce a transfer of custody.

This point is critical for classification. The absence of extradition does not justify any particular action on its own, but historically it has been a necessary precondition in cases where capture rather than surrender occurs.

Capture versus extradition

What followed was not an extradition. No Venezuelan court ordered a surrender. No executive authority within Venezuela transferred custody through legal process. Instead, U.S. authorities obtained physical custody directly and transported the accused individuals into U.S. control.

From a terminology standpoint, this distinction matters. Extradition is a consensual, treaty-based transfer between states. What occurred here is more accurately described as capture or seizure, followed by transfer to civilian custody. These terms are used in both domestic case law and historical precedent to describe situations where custody is obtained without host-state consent.

Transfer to civilian courts

Following the capture, the accused were transferred into the U.S. criminal justice system. They were placed in federal custody to face existing charges in civilian court. No military tribunal was invoked. No ad hoc judicial mechanism was created. The procedural destination was the same one contemplated when the indictments were first filed: a federal courtroom.

This sequence is consistent with prior cases where capture-for-prosecution has occurred. The endpoint is not indefinite detention or political negotiation, but adjudication through ordinary criminal process.

What this section does not conclude

This timeline does not answer whether the capture was lawful under international law. It does not assess the strength or weakness of the charges. It does not defend or condemn the policy decisions that led to the operation. Those questions are important, but they belong to later stages of analysis.

What this section establishes is the procedural shape of the event. There were existing charges. Extradition was unavailable. Custody was obtained through capture rather than surrender. The accused were transferred into civilian courts for prosecution.

Only once those facts are clear can we responsibly ask the next question: whether this sequence fits within a broader historical pattern, or whether it represents something genuinely new.

The Legal Confusion

International Law and Domestic Jurisdiction Are Not the Same Thing

Much of the confusion surrounding this event stems from a category error. Public discussion often treats international law and domestic criminal law as if they operate on the same plane and produce the same outcomes. They do not. They answer different questions, govern different relationships, and provide different remedies.

Until that distinction is made clear, almost every downstream argument becomes tangled.

What international law actually governs

International law primarily regulates the conduct of states toward one another. Its core concern is sovereignty: who has authority over territory, airspace, borders, and the use of force. Under the framework established by the United Nations Charter, states are generally prohibited from exercising law-enforcement powers inside another sovereign state without consent.

From that standpoint, unilateral capture on foreign soil raises serious international law questions. Those questions are real, and they are not trivial. They concern potential violations of sovereignty, the prohibition on the use of force, and the proper remedies available between states.

What international law does not do is automatically determine the validity of criminal proceedings inside a domestic court once a defendant is physically present.

This distinction is often missed in public commentary.

What domestic criminal law governs

Domestic criminal law governs a different relationship entirely: the relationship between a court and a defendant. In the United States, federal courts ask a narrow set of questions when determining whether a case may proceed:

- Does the court have subject-matter jurisdiction over the charged offenses?

- Is there a valid indictment?

- Is the defendant physically present before the court?

Historically, U.S. courts have answered those questions without inquiring into the diplomatic or international legality of how the defendant arrived in custody. This principle is long-standing and well documented.

The separation of capture and jurisdiction

U.S. case law has repeatedly affirmed that the manner of a defendant’s capture does not, by itself, deprive a court of jurisdiction. This principle is commonly associated with a line of cases beginning with Ker v. Illinois (1886) and reaffirmed in Frisbie v. Collins (1952). The doctrine was most directly tested in the modern era in United States v. Alvarez-Machain (1992), where the Supreme Court held that a defendant abducted from a foreign country could still be tried in U.S. court.

The Court’s reasoning was not that international law concerns were irrelevant. Rather, it held that such concerns address state responsibility and diplomatic remedies, not the court’s authority to adjudicate a criminal case. Those issues are handled through political and diplomatic channels, not through dismissal of charges.

This distinction is critical. International law may judge an action wrongful. Domestic courts may still proceed. Both things can be true at the same time.

Why this distinction matters for classification

When media coverage implies that an alleged violation of international law automatically invalidates prosecution, it sets expectations that history does not support. In prior cases where capture-for-prosecution occurred, international objections were raised, debated, and sometimes formally recorded. None of those objections resulted in courts relinquishing jurisdiction over defendants already in custody.

This does not mean international law is meaningless. It means it operates in a different arena, with different tools and timelines.

Failing to separate these categories leads to a distorted understanding of what is likely to happen next. Observers expect reversals that rarely occur, or they assume that prosecution itself proves legitimacy of the capture. History supports neither conclusion.

Head-of-state status and immunity

Complicating matters further is the question of head-of-state immunity. International law generally recognizes personal immunity for sitting heads of state from foreign criminal jurisdiction. That doctrine, however, governs whether a court may exercise jurisdiction, not whether a state possesses unilateral authority to capture.

In practice, capturing states often deny that the individual qualifies for immunity under their recognition policies, while other states disagree. Those disputes are typically resolved after custody is obtained, not before. Again, this does not eliminate controversy, but it reflects how these cases have historically unfolded.

Why clarity here is essential

Without this legal separation, the public conversation collapses into false binaries: either the capture was lawful and prosecution is valid, or the capture was unlawful and prosecution must collapse. History shows that reality is more complex.

International law addresses relations between states. Domestic criminal law addresses adjudication of crimes. Conflating the two produces confusion, not clarity.

With this distinction in place, we can now ask the next question more responsibly: whether the sequence of indictment, failed extradition, capture, and prosecution fits within a recognizable historical pattern.

That is where history becomes indispensable.

The Historical Pattern

Rare, Narrow, and Repeating

Once the legal categories are clarified, the next question becomes unavoidable: has this sequence of events happened before?

The answer is yes—but rarely, narrowly, and under specific conditions. History does not present a large collection of comparable cases. Instead, it offers a small cluster spread across decades, each treated as exceptional in its own time, yet sharing a remarkably similar structure when examined closely.

This is not a pattern of routine law enforcement. It is a pattern of last resort.

The recurring structure

Across the historical record, cases that resemble the current situation tend to share six core features:

- Formal criminal charges precede capture Indictments or arrest warrants are issued well in advance. The capture does not create the case; it executes an existing one.

- Extradition is unavailable or refused Either no functioning extradition treaty exists, or the territorial state refuses cooperation.

- The individual is treated as a fugitive under domestic law This classification reflects unresolved charges and absence from the court’s jurisdiction.

- Custody is obtained by capture, not surrender Physical control is taken without a formal transfer by the host state.

- The stated end point is civilian prosecution The individual is brought before ordinary criminal courts, not held indefinitely or resolved through diplomacy alone.

- International objections follow, but custody remains Sovereignty protests and legal objections arise, but they do not result in the return of the defendant.

This structure does not appear often, but when it does, it appears with striking consistency.

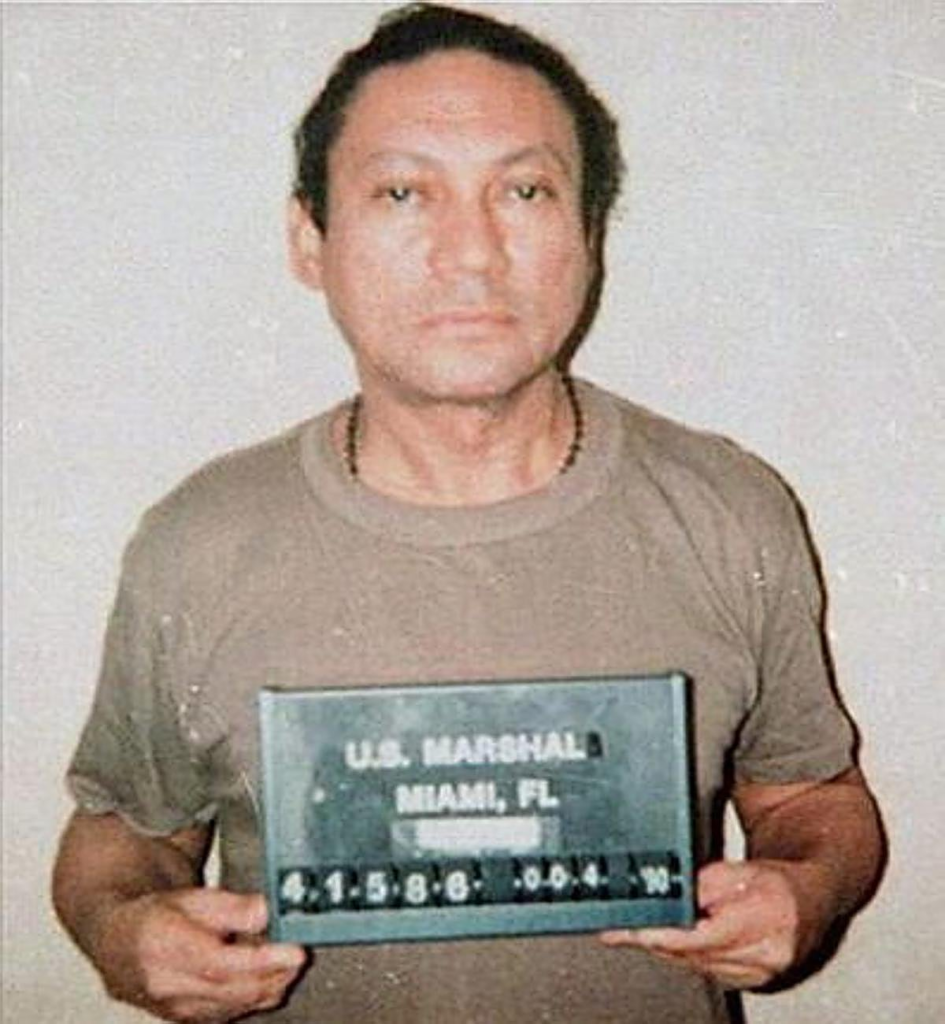

Manuel Noriega (1989)

The closest modern parallel remains Manuel Noriega, the de facto leader of Panama in the late 1980s.

Noriega was indicted in U.S. federal court on drug trafficking charges before U.S. military action took place. Extradition was not a realistic option. During the U.S. invasion of Panama, Noriega was captured and transferred to the United States, where he was tried in civilian court and convicted.

International objections were immediate. The United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion. Sovereignty violations were widely alleged. None of these actions resulted in the dismissal of charges or Noriega’s return. The criminal case proceeded independently of the diplomatic fallout.

From a structural standpoint, every major element of the pattern is present.

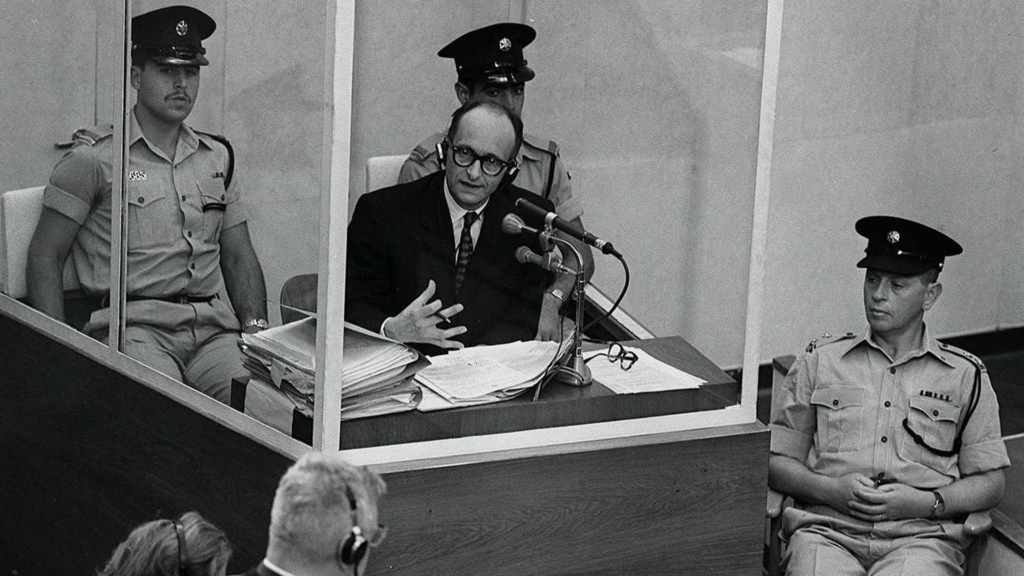

Adolf Eichmann (1960)

An earlier and more widely known case is Adolf Eichmann, captured by Israeli agents in Argentina.

Eichmann had been charged under Israeli law for crimes committed during the Holocaust. Argentina did not consent to his removal. He was captured, transported to Israel, tried in civilian court, and convicted.

The international response followed a familiar trajectory. Argentina protested the violation of its sovereignty. The matter was raised at the United Nations. Israel acknowledged the breach but did not return Eichmann. The criminal proceedings continued.

This case illustrates a key historical reality: international law disputes over capture do not necessarily undo domestic prosecution once custody is established.

United States v. Alvarez-Machain (1990–1992)

The case of Humberto Álvarez-Machain is structurally different in scale but crucial in legal precedent.

Álvarez-Machain was indicted in the United States for his alleged role in the killing of a U.S. DEA agent. Mexico refused extradition. He was abducted and brought to the United States to stand trial.

The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which held that the manner of capture did not deprive U.S. courts of jurisdiction. The Court explicitly separated international law concerns from domestic criminal adjudication.

This case is often cited not because of who Álvarez-Machain was, but because it clarifies how courts handle capture-for-prosecution scenarios.

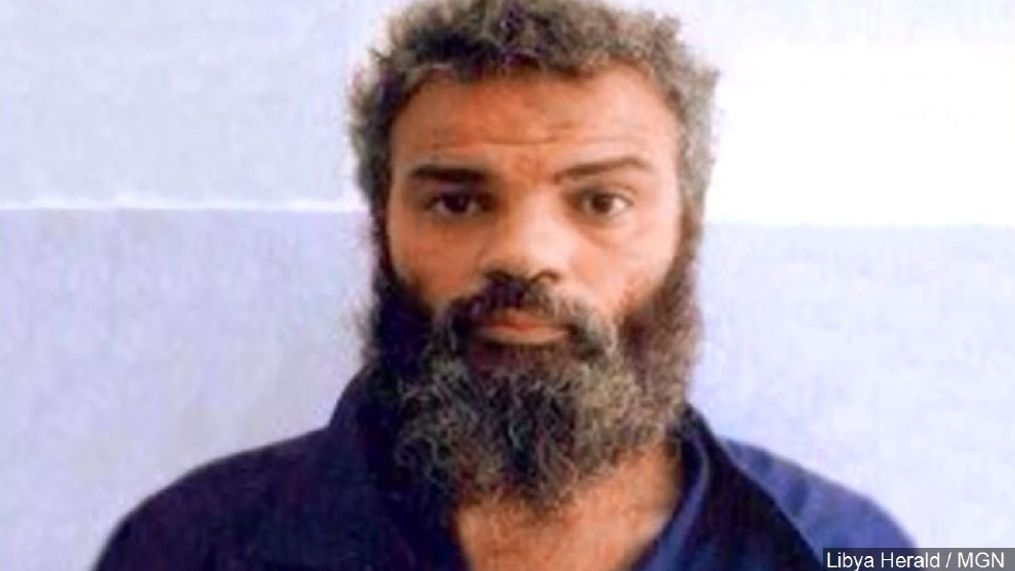

Ahmed Abu Khattala (2014)

A more recent example is Ahmed Abu Khattala, accused of involvement in the Benghazi attacks.

Khattala was indicted in U.S. court and captured by U.S. forces in Libya, where no functioning extradition process existed. He was transferred to the United States, tried in civilian court, and convicted on some charges.

Once again, international law concerns were raised, but custody and prosecution were not reversed.

What the pattern does—and does not—prove

These cases do not prove that capture is lawful under international law. They do not prove that charges are just or outcomes correct. They do not establish a general right for states to seize individuals abroad.

What they demonstrate is narrower and more precise: when certain conditions converge—pre-existing charges, failed extradition, fugitive status, and capture-for-prosecution—states have, on rare occasions, acted outside normal extradition channels and proceeded to trial despite international objections.

History does not normalize this pattern. It documents it.

And that distinction matters.

With the pattern established, the next step is to address an understandable objection: each of these cases occurred in very different political and historical contexts. The question, then, is whether those differences invalidate the pattern or merely shape its consequences.

That is where we turn next.

Each Case Is Unique

Why Uniqueness Shapes Consequences, Not Categories

At this point, a common objection naturally arises: Yes, similar things have happened before—but this case is different. The countries are different. The political stakes are different. The global context is different. All of that is true.

The mistake is assuming that difference in circumstance automatically dissolves similarity in structure.

History routinely distinguishes between category and consequence. Categories are defined by process. Consequences are shaped by context. Confusing the two leads to analytical error.

Uniqueness is real—and expected

No two historical events are identical. Panama in 1989 was not Argentina in 1960. Libya in 2014 was not Mexico in 1990. Venezuela today is not any of them. Each case unfolded within its own geopolitical environment, under its own pressures, with its own downstream effects.

These differences matter deeply when evaluating:

- Diplomatic fallout

- Regional instability

- Economic consequences

- Long-term legitimacy

But those differences have never been the criteria by which courts or historians determine whether an event belongs to a recognizable class.

How history actually classifies events

When historians and legal scholars classify events, they ask a narrower set of questions:

- Were there pre-existing charges?

- Was extradition unavailable?

- How was custody obtained?

- What legal process followed?

- How did international objections interact with domestic proceedings?

These are structural questions. They do not disappear because the state involved is larger, wealthier, or more geopolitically significant.

Panama’s size did not make Noriega’s capture legally unique. Israel’s moral standing after the Holocaust did not change the jurisdictional questions raised by Eichmann’s abduction. Libya’s instability did not redefine the legal posture of Abu Khattala’s prosecution.

In each case, context influenced reaction, not classification.

Scale affects impact, not structure

Much of the current confusion stems from treating scale as a legal differentiator. Venezuela is a major oil-producing nation. Its alliances are global. Its internal collapse carries regional consequences. None of that is trivial.

But scale does not determine whether an event fits a pattern. It determines how loudly the pattern reverberates.

History shows that when capture-for-prosecution occurs in small states, the consequences are limited. When it occurs in larger or more connected states, the consequences are amplified. The structure, however, remains the same.

Failing to distinguish these layers leads to overstatement. Observers assume that because the impact is larger, the category must be different. That assumption does not hold up under historical scrutiny.

Why this distinction matters

If uniqueness alone were enough to invalidate historical comparison, history itself would become unusable. Every event would be unprecedented by definition. Patterns would never exist, only moments.

But history works precisely because it recognizes that patterns persist even when circumstances change. That recognition does not excuse actions or justify outcomes. It allows for understanding before judgment.

In this case, acknowledging uniqueness does not erase the historical pattern. It explains why reactions are more intense, why consequences may be broader, and why the stakes feel higher. It does not transform the event into something structurally new.

With that clarification in place, we can now address the final piece of the puzzle: why modern media coverage consistently struggles to recognize this distinction, and how that struggle shapes public perception.

That is where we turn next.

Where Mainstream Media Framing Breaks Down

Why Rare Patterns Are Treated as Unprecedented Crises

At this point, the disconnect between historical pattern and contemporary coverage becomes clearer. The issue is not that mainstream media lacks intelligence or access to information. It is that modern media systems are optimized for speed, emotion, and immediacy, while rare-but-recurring historical patterns require patience, comparison, and classification.

When those two realities collide, predictable framing failures emerge.

Novelty bias: treating rarity as newness

The first and most common breakdown is novelty bias. Because capture-for-prosecution events occur infrequently, they are treated as if they have no historical antecedents. Headlines lean heavily on words like “unprecedented,” “extraordinary,” or “without parallel,” not because those claims have been tested against history, but because the event falls outside recent memory.

History, however, does not operate on a twenty-four-hour news cycle. Events that recur once every few decades are still part of a pattern. The fact that most journalists and readers have not lived through a comparable case does not make the case historically unique.

When novelty bias takes hold, context collapses and reaction fills the gap.

Personalization over structure

A second breakdown occurs when structural events are narrated almost entirely through personalities. Coverage becomes centered on individual leaders, administrations, or political figures, rather than on legal posture and process.

This personalization creates a distorted lens. The story becomes about who acted, what they intended, or what kind of person they are, rather than about the procedural sequence that unfolded. History shows that the same structural logic has been applied to very different people across time, which suggests that personality is not the decisive variable.

When coverage cannot explain the event without naming the individuals involved, it has likely failed to identify the category.

Treating norms as enforcement mechanisms

Another recurring error is treating international norms as if they function like enforceable criminal statutes. Media framing often implies that because an action may violate international law, it cannot stand or must be reversed.

Historical precedent does not support that expectation. International law shapes diplomatic protest, reputational cost, and long-term state behavior. It does not routinely unwind domestic criminal proceedings once custody is established. Treating norms as automatic enforcement mechanisms leads audiences to expect outcomes that rarely occur.

This is not a defense of the system. It is a description of how it has functioned.

Omission of tested precedent

Mainstream coverage frequently references abstract principles while omitting concrete cases where those principles were tested. Sovereignty is discussed without Eichmann. Due process is discussed without Álvarez-Machain. Law enforcement overreach is discussed without Noriega.

The result is an inverted evidentiary hierarchy: theory is foregrounded, history is sidelined. Readers are given ideals without examples, which makes the present moment appear detached from the past.

This omission is not usually intentional. It is a consequence of space constraints, audience attention limits, and the assumption that precedent is background rather than evidence.

Moral evaluation before classification

Media coverage often moves quickly to moral judgment: Was this right? Was this dangerous? Was this abuse of power? These are legitimate questions. The problem is timing.

History teaches that moral evaluation without prior classification leads to unstable conclusions. Different categories of events carry different moral frameworks. A capture-for-prosecution event behaves differently than a regime-change war, even if both involve force and foreign territory.

When classification is skipped, moral language does the work of explanation, and nuance is lost.

Compressing process into spectacle

Another failure point is temporal compression. Multi-year legal processes are reduced to a single dramatic moment: the raid, the arrest, the transfer. When the process disappears, the action appears impulsive rather than procedural.

History shows that these cases are rarely spontaneous. They are the endpoint of long legal and diplomatic dead ends. Compressing that history into spectacle makes the event feel lawless even when it follows a recognizable sequence.

Confusing scale with category

Finally, coverage often assumes that because the country involved is large, oil-rich, or geopolitically significant, the legal category must be different. Scale matters. It affects consequences. It shapes international reaction. It raises stakes.

But scale does not determine classification. History categorizes events by how they unfold, not by how widely they reverberate.

When scale is mistaken for category, analysis drifts toward alarmism.

The cumulative effect

Taken together, these framing failures create a predictable outcome. The event is presented as unprecedented. The public is told that norms have collapsed. Emotional reactions dominate. Historical memory fades.

This does not mean concern is illegitimate. It means concern is being shaped by incomplete classification.

Understanding where media framing breaks down does not require rejecting journalism. It requires recognizing its limits, especially in moments where history moves slowly and headlines move fast.

With that diagnosis in place, one final clarification remains. Even when patterns are real and classification is accurate, there are important things history cannot tell us in advance. Recognizing those limits is part of intellectual honesty.

That is where we turn next.

What This Pattern Does Not Tell Us

The Necessary Limits of Historical Comparison

At this stage, it is important to slow the analysis down once more. Pattern recognition is a tool for understanding, not a shortcut to certainty. History can help classify events, but it cannot resolve every question those events raise.

Recognizing that this situation fits a rare historical pattern does not answer several important questions, and pretending otherwise would undermine the very discipline this article has tried to model.

First, the pattern does not determine guilt or innocence.

Historical comparison says nothing about whether the charges involved are valid, weak, overstated, or politically motivated. Courts exist precisely because evidence must be weighed carefully and publicly. History can clarify categories, but it cannot replace adjudication.

Second, the pattern does not render moral judgment.

Identifying precedent does not mean endorsing outcomes. History records what has happened, not what ought to have happened. Confusing description with approval is a common error, and one this article intentionally avoids.

Third, the pattern does not predict long-term consequences.

Each case unfolds differently after capture. Some lead to convictions, some to acquittals, some to diplomatic standoffs, and some to quiet normalization. History shows possible trajectories, not guaranteed ones.

Fourth, the pattern does not justify policy decisions.

Understanding that similar actions have occurred before does not automatically legitimize present choices. It simply establishes that those choices belong to an existing category rather than an invented one.

Finally, the pattern does not eliminate legitimate concern.

Rare events are often unsettling for good reason. Classification should steady analysis, not anesthetize conscience. The goal is clarity, not complacency.

Holding these limits in view protects the analysis from overreach. It reminds us that discernment requires both understanding and restraint.

A Biblical Worldview of Discernment, Power, and Restraint

Why Classification Comes Before Condemnation

A biblical worldview does not ask us to ignore power or excuse its misuse. Scripture is clear-eyed about authority, justice, and human fallibility. But it also insists on a particular posture when confronting complex and emotionally charged events.

That posture begins with listening before speaking and understanding before judging.

Proverbs warns that “the one who gives an answer before he hears—it is folly and shame to him.” That wisdom applies not only to personal relationships, but to public life. Reaction without understanding produces noise, not truth.

Scripture also recognizes that authority is real and consequential. Romans 13 describes governing authority as part of an ordered world, accountable to God and constrained by justice. That does not sanctify every action of the state, but it does require seriousness and care when evaluating state power.

Equally important is the biblical prohibition against bearing false witness. Exaggeration, panic, and careless framing distort reality just as surely as outright lies. When events are stripped of context or misclassified through haste, truth suffers.

A biblical worldview, then, does not demand that Christians defend governments or condemn them reflexively. It demands something quieter and harder: patience, intellectual honesty, and a refusal to let emotion outrun truth.

This article’s insistence on classification before condemnation is not merely academic. It is a moral discipline. It reflects a commitment to truthfulness in a moment when outrage is easier than understanding.

Conclusion

Learning to Think Before We React

Moments like this test more than political loyalties. They test our capacity for discernment.

When rare events occur, the pressure to declare them unprecedented is strong. Shock creates urgency, urgency creates reaction, and reaction often bypasses understanding. History, by contrast, moves slowly. It asks us to compare, to remember, and to resist the temptation to treat every disruption as a collapse of order.

What we have seen is not a common event. Capture-for-prosecution is rare, serious, and consequential. But rarity is not the same as novelty. History shows that when indictments exist, extradition fails, and fugitives remain beyond reach, states have—on rare occasions—acted outside normal channels and then absorbed the legal and diplomatic fallout.

Recognizing that pattern does not settle the debate. It steadies it.

The task of responsible citizenship, and faithful discipleship, is not to react fastest or speak loudest. It is to think clearly, tell the truth carefully, and judge rightly, in the proper order.

History helps us do that, if we are willing to listen.

And Scripture reminds us why it matters.

References

Primary Legal and Judicial Sources

Israeli Supreme Court. (1962). Attorney-General of the Government of Israel v. Adolf Eichmann (Criminal Appeal 336/61). State of Israel.

United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. (1992). United States v. Manuel Noriega, 746 F. Supp. 1506.

United States Supreme Court. (1886). Ker v. Illinois, 119 U.S. 436.

United States Supreme Court. (1952). Frisbie v. Collins, 342 U.S. 519.

United States Supreme Court. (1992). United States v. Alvarez-Machain, 504 U.S. 655.

United States District Court for the District of Columbia. (2017). United States v. Ahmed Abu Khattala, Criminal No. 14-141.

United States Government Sources

United States Department of Justice. (2020). United States v. Nicolás Maduro Moros et al.: Indictment. https://www.justice.gov

United States Department of State. (n.d.). Extradition treaties and agreements. https://www.state.gov

United States Department of Justice. (n.d.). Fugitive status and federal criminal procedure. https://www.justice.gov

International Law and Treaty Sources

United Nations. (1945). Charter of the United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter

United Nations General Assembly. (1960). Question of the violation of the sovereignty of a State (Resolution 138). https://digitallibrary.un.org

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (Various years). World drug reports. https://www.unodc.org

Historical and Scholarly Sources

Bass, G. J. (2000). Stay the hand of vengeance: The politics of war crimes tribunals. Princeton University Press.

Bassiouni, M. C. (2011). Introduction to international criminal law (2nd ed.). Martinus Nijhoff.

Cassese, A. (2005). International law (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Schabas, W. A. (2017). An introduction to the International Criminal Court (5th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Media Coverage

(These sources are cited to demonstrate framing and narrative tendencies, not as primary authorities.)

Cable News Network. (2026). Coverage of the capture of Nicolás Maduro. https://www.cnn.com

The New York Times. (2026). Reporting on Venezuela and U.S. legal actions. https://www.nytimes.com

The Guardian. (2026). Analysis of international law implications in Venezuela. https://www.theguardian.com

Reuters. (2026). Timeline and diplomatic reaction to U.S. actions in Venezuela. https://www.reuters.com

Biblical Sources

The Holy Bible, Legacy Standard Bible. (2021). Lockman Foundation.

Note on sources:

Primary legal documents, court rulings, and treaty texts are cited as authoritative sources for historical pattern and legal classification. Media sources are included solely as illustrative examples of contemporary framing and are not treated as primary evidence.