Part 3 of Civic Theology: How the Bible Shaped America’s Founding and Freedom

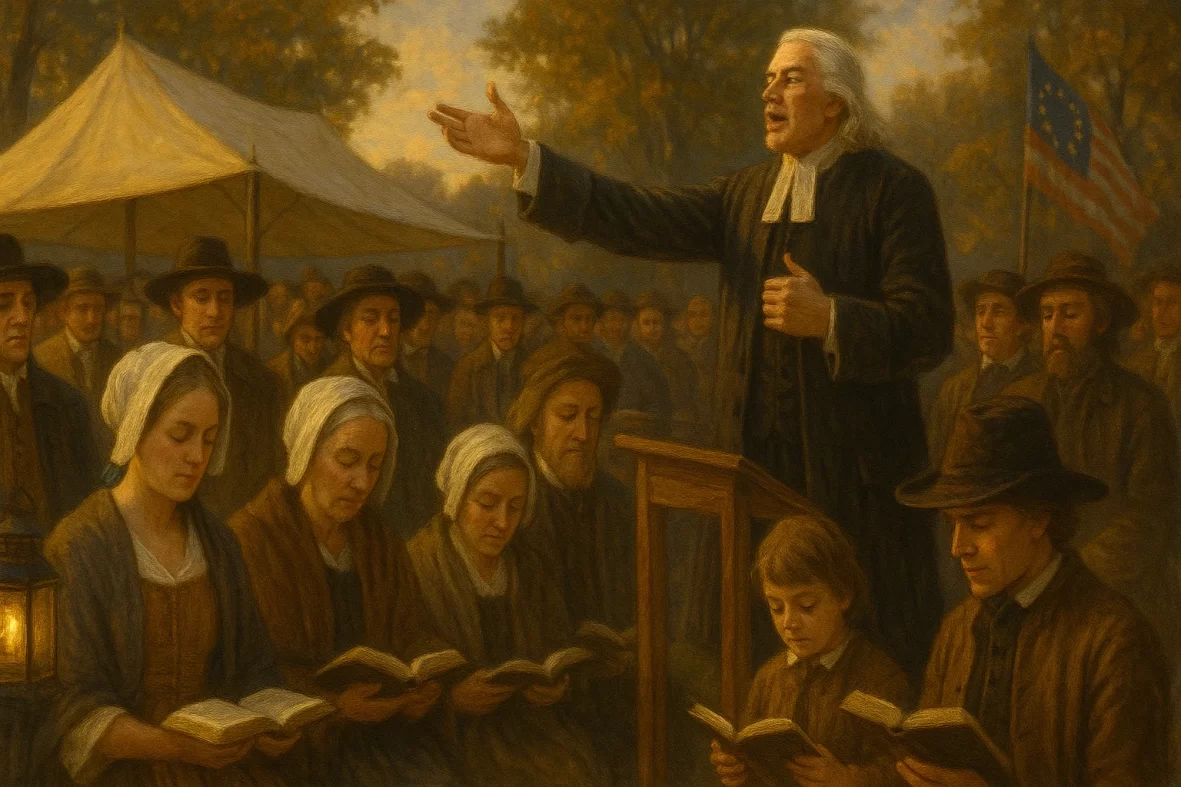

In the mid-1700s and again in the early 1800s, the American colonies and young nation were swept by waves of intense religious revival. These Great Awakenings emphasized personal conversion and a direct encounter with God (Acts 2:17–21; John 3:3), rekindling a fervor that had lain dormant. Preachers like Jonathan Edwards in New England and George Whitefield who crisscrossed the colonies insisted that individuals must be “born again” to see God’s kingdom (John 3:3) . This focus on spiritual rebirth – not church rituals or family ties – challenged old hierarchies in church and society. As one historian notes, Awakening leaders stressed that “God did not work exclusively through kings or bishops, but through the people themselves,” instilling in ordinary men and women a new sense of personal authority and conscience . In this way, the revivals had civic as well as spiritual consequences: they nurtured ideas of equality and freedom that later blended with the American ethos of self-government.

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting of Jesus and Nicodemus illustrates the Awakening theme of being “born again” (John 3:3). Early American revivalists seized on this Scripture to emphasize that each person must experience an inner spiritual birth – a conviction that led many to claim a direct, personal relationship with God and reject mere outward religion.

The First Great Awakening: 1730s–1740s

The First Great Awakening (c. 1730–1740) began amid a broader Enlightenment culture. As secular rationalism and comfort lulled many colonists into complacency, itinerant preachers arose with an urgent message of sin and salvation . Jonathan Edwards, a Puritan minister in Northampton, Massachusetts, thundered that God was “angry” with sinners and that only the elect would be saved. In his famous sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, Edwards reminded listeners of the necessity of total dependence on God’s grace. He often interpreted local hardships as divine warnings: for example, when drought hit Northampton in 1736, Edwards told the farmers that their own “corruption in our hearts” had angered God, and only true repentance and charity would “remove those judgments” . This idea drew directly on Puritan covenant theology (cf. John Winthrop’s 1630 charge that New England must obey God’s covenant or face His wrath ). It helped awaken a sense that communal well-being depended on moral faithfulness.

A central emphasis of the Awakening was individual conversion. Edwards and others taught that without a dramatic inner change one could not really “see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3) . Correspondingly, converts began referring to themselves as “New Lights” who had been regenerated by the Holy Spirit . These New Lights insisted that salvation came through faith alone, not by church membership or good deeds. This revolutionary gospel leveling – the idea that each person must decide to follow Christ – implicitly undermined the old social order. As one historian explains, because revivalists taught that God “acted through the heart and commitment of each individual, [the believer] need not look beyond himself for any source of authority” . In practice this meant that churches and even governments seemed secondary to the authority of one’s own conscience.

Two towering figures – Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield – gave the First Awakening its momentum. Edwards stayed primarily in New England, meticulously recording hundreds of conversions, but Whitefield traveled throughout the colonies (and England), preaching outdoors to any crowd that could gather. In one remarkable year Whitefield covered some 5,000 miles and delivered over 350 sermons . He drew multitudes everywhere – from taverns to forest glades – including women, slaves, and Native Americans, astonishing contemporaries with his charisma . Even skeptics like Benjamin Franklin were captivated by Whitefield’s passion. Their combined efforts sent revival fever through Massachusetts, Connecticut, Virginia, and beyond. By the late 1740s, colonial churches were transformed: many who had been dormant became fervent believers, and new denominations (Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians) rapidly multiplied . The Great Awakening thus helped knit the colonies together in a shared spiritual experience and instilled American Protestantism with a deep evangelical zeal.

Awakening Theology:

Freedom of Conscience and Covenant

Theologically, the Awakening reemphasized classic Puritan convictions while adapting to new contexts. The Puritans had long taught a “covenant of grace” – that God promised salvation to those who truly repented – and they also believed their own society was in a covenant with God (as Winthrop’s “city on a hill” metaphor expressed ). Edwards and Whitefield inherited this mindset. They insisted that the Holy Spirit sovereignly chose who would be “born again” (echoing Romans 8:28–30), but they poured this doctrine into preaching that fiercely urged individual response. The result was compatibilism: even as God was sovereign, people were morally responsible. Finney later summed it up: “Unbelief was a ‘will not,’ instead of a ‘cannot’” – people freely rejecting the Spirit, not doomed by fate . In practical terms, the Awakening’s teaching on freedom of will gave believers a taste of spiritual liberty. Galatians 5:1 (“For freedom Christ has set us free, stand firm therefore…”) rang true in revival meetings: to be “free in Christ” meant no longer enslaved to sin or to hollow rituals. Likewise, Acts 2:17–21 (the Joel prophecy that God would pour out His Spirit on all people “in the last days”) was seized upon by many preachers. They viewed their era as the fulfillment of Joel’s promise, a divine warrant for powerful conversion experiences. In short, revival theology promoted soul liberty: each person stood free and responsible before God, a concept that foreshadowed later American ideals of conscience and equality.

Edwards took this further with his vision of a national covenant. He believed that just as ancient Israel was bound by covenant, so New Englanders were a “peculiar people” under divine judgment or blessing . He saw good harvests and prosperity as signs of God’s mercy, and calamities (plagues, wars) as warnings to repent. In Edwards’s view, only a mass conversion could cleanse society. He called passionately for a genuine awakening – a spiritual renewal to “restore [the nation’s] virtue” – so that liberty and property could be enjoyed in peace . He argued that political freedom alone was fragile: “Madison and Jefferson are right” to protect civil rights, but “without freedom for religion… political and economic freedom… will erode the social order” . In other words, a republic needed a virtuous, awakened church to survive. Thus, Edwards (drawing on the same national-covenant tradition as Winthrop) linked revival with America’s destiny – believing that God had commissioned the new nation to be a model of righteousness.

The Second Great Awakening:

1800s Revival and Reform

After the Revolution, a Second Great Awakening (c. 1790–1840) spread revival over an even broader canvas. Western migrants, city dwellers, and new immigrants sought meaning in tumultuous times. Camp meetings – large outdoor rallies of prayer and preaching – epitomized this era. One famous example was Cane Ridge, Kentucky (1801), where for a week thousands gathered under tents and trees. “Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian preachers all delivered passionate sermons… exhorting the crowds to strive for their own salvation,” often preaching from open-air pulpits (even tree stumps) . The emotional response was astonishing: attendees “cried, jumped, spoke in tongues, or even fainted” under the fervent preaching . Revivalism in this period truly “captured the democratizing spirit of the American Revolution” . Frontier preachers welcomed people of all backgrounds into the faith; women began speaking at meetings; and itinerant circuit-riders (especially Methodists) required nothing more than conversion and a “call” to preach. In effect, orthodox Calvinist training gave way to a more egalitarian clergy: a cotton mill worker who experienced conversion could almost overnight become a circuit preacher alongside aristocratic ministers .

Charles Finney (1792–1875) became the Second Awakening’s best-known minister in the Northeast. A former lawyer turned revivalist, Finney brought radical innovations: he famously introduced the “anxious bench” and urged women to pray publicly – controversial measures at the time . Theologically, Finney departed from old Calvinism by denying that people have an inherited sinful nature. Instead, he taught that the sinner has a choice – he is “the author of the change” in conversion . For Finney, individual will and moral effort were key: humans could indeed choose to accept Christ, and revival could be won by faithfulness and prayer. This emphasis on human agency dovetailed with political democracy. The egalitarian message that “all souls are equal in salvation” resonated with Americans who had fought monarchy. In fact, second-Awakening preachers preached a new spiritual egalitarianism – that anyone could be saved – just as new-state constitutions were proclaiming equal rights for white men .

The Second Awakening also explicitly linked faith and social reform. Finney and his colleagues saw the Gospel as a force to remake society. “One historian said that [Finney] unleashed a mighty impulse to social reform by insisting that new converts make their lives count for the Kingdom of God” . At Finney’s Oberlin College and beyond, revivalism became intertwined with abolitionism, temperance, and education. Students refused to accept slaveholders as elders; Oberlin became a hub for anti-slavery activity and even a stop on the Underground Railroad . Finney himself “preached against slavery and fought for abolition and cared deeply about African-American civil rights” . He linked churches to abolitionist societies, believing that true religion must confront the sin of slavery. In short, the “Second Awakening” gave evangelical religion a postmillennial optimism – the belief that Christians could build a just society on earth – and this vision propelled major democratic impulses. The revivals taught that if Christians would actively pursue liberty and justice, they were partnering with God’s own mission (compare Acts 2:17–21).

Revival Theology and America’s Covenant Calling

Taken together, the Great Awakenings helped forge a uniquely American outlook on freedom and faith. Revivals underscored individual “liberty of conscience”: each person stood accountable directly to God (Galatians 5:1). At the same time, revivalists often saw the nation as under divine covenant. Americans believed their liberty was not merely a human achievement but a trust from God. The Awakening preachers taught that God had entrusted this “experiment in self-government” to believers who would uphold moral laws. In this sense, revival theology fed a sense of national mission. Many early Americans felt called to build a “city on a hill” that served God, and revivals confirmed that conviction. The conflagration of faith and freedom encouraged democracy: as spiritually awakened individuals claimed equal standing in the church, so they felt entitled to political equality. The First and Second Awakenings thus poured spiritual fuel on America’s covenantal vision of freedom.

In reflecting on the Great Awakenings, we see how revival and liberty intertwine. The revivals reminded Americans that true liberty is not just doing as one pleases, but living righteously before God. Jesus’ words, “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:32), became alive in America’s history: those “born again” (John 3:3) were set free from sin and, in turn, became champions of justice. Across the awakenings, churches no longer served overlords but the people, and Americans more broadly began to cherish the idea that conscience cannot be coerced. In this way, revival theology became part of America’s DNA. As one historian observes, “the Great Awakening added its measure of opposition [to hierarchy], the old institutions began to crumble” . In the end, God’s providence through revival gave rise to a liberty mindset grounded in a holy cause – a legacy that would spur abolitionists and inform the nation’s covenantal sense of destiny.

Reflective Questions

- How did the revivalist emphasis on personal rebirth (John 3:3) challenge established authority in both church and state?

- In what ways did the Great Awakenings contribute to American ideals like equality and democracy?

- Considering the covenantal theology of the Awakening era, what duties do believers have toward the nation today?

These questions invite us to ponder how America’s faith heritage – shaped by the First and Second Awakenings – can guide our understanding of liberty and responsibility now.

Conclusion

The Great Awakening revivals show that spiritual revival and civic freedom often go hand in hand. When God’s people experienced fresh convictions, new senses of mission and conscience flourished. The Awakening’s gospel that each soul matters before God helped inspire a culture where every person demanded moral and political rights. Conversely, the liberty born from the American revolution created open soil for revival – no state church stood in the way of these ferocious outpourings of faith. In the end, the First and Second Great Awakenings remind us that America’s story has always been woven with both the promise of religious liberty and the call to godly living. Just as the early revivalists believed that true freedom required a heart turned toward God, so America’s enduring covenantal promise depends on the moral vitality of its citizens (Gal. 5:1; Acts 2:17–21).

Part 4 Preview: In the next installment of this series we will examine how the principles of religious revival and liberty developed in the 19th century, as revivalist fervor fueled new reform movements and tested the nation’s commitment to freedom of conscience.

References

Gullotta, D. N. (2016, August 30). The Great Awakening and the American Revolution. Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved from https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/08/great-awakening-american-revolution

Locke, J., & Wright, B. (Eds.). (2018). The American Yawp (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.americanyawp.com (See Ch. 10: Religion and Reform)

McDermott, G. R. (2018). Jonathan Edwards on property, liberty, and the national covenant. Journal of Markets & Morality, 21(2), 259–270.

Christian History Magazine (n.d.). Charles Grandison Finney: Father of American Revivalism. Christian History Institute. Retrieved from https://christianhistoryinstitute.org (See sections on Oberlin and abolition)

Holy Bible: Legacy Standard Bible. (2021). (2nd ed.). Legacy Standard. (Original work published 1782)

Want to explore further?

Dig Deeper into Civic Theology