Part 9 of Civic Theology: How the Bible Shaped America’s Founding and Freedom

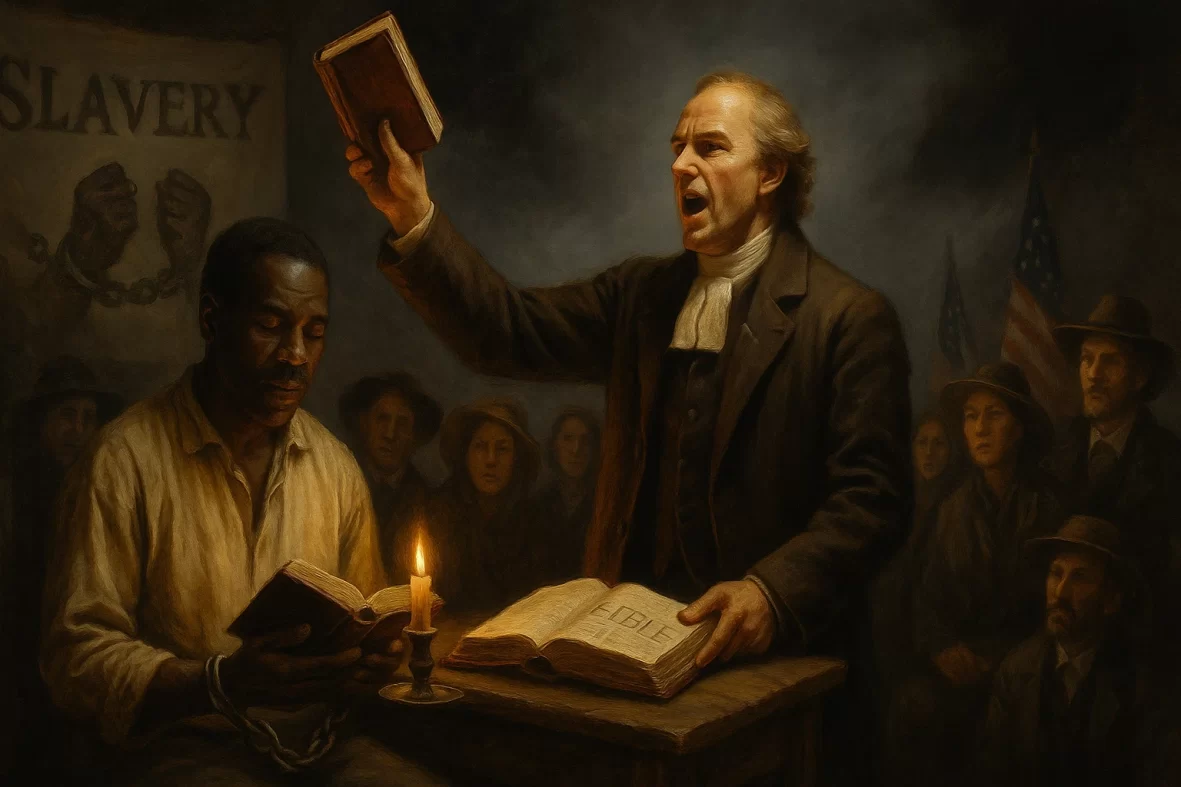

The Bible was weaponized by slaveholders in early America to defend a cruel status quo. Pro-slavery apologists pored over Scripture like Ephesians 6:5 (“Servants, obey your earthly masters…as to Christ” ) and old Testament household codes, claiming God ordained human bondage. They misread what was descriptive of ancient social realities as prescriptive commands. But this was a deeply distorted view. Biblical slavery laws often come with human-rights safeguards (e.g. annual rest for slaves, humane treatment, and ultimate release) and apply within a sinful culture, not outside it. (Note also that “servant” in Scripture was never a racial caste.) In fact, the prophets and the gospel often speak of God’s design for true freedom. The slaveholders’ “Christianity” was really a pretended piety by which they called brutality a Christian duty . As Bishop William Meade argued, suffering at the hands of a cruel master was simply payment for sin . Such arguments twist God’s word: they ignore that the Spirit-breathed Scriptures give a higher ethical law grounded in the image of God, love, and justice. All people bear God’s image (Gen 1:27), and the gospel calls all slaves to Christ not to acquiesce in oppression but to be free in Him.

Illustration: The open Bible in the church pew reminds us that all Scripture must be read in the light of Christ’s love. Early Americans often quoted Ephesians 6:5 and other texts to demand slave obedience , but this misread ignores the Bible’s overarching ethic. True biblical faith affirms that every person—slave or free—is created in God’s image and worthy of dignity (Gal. 3:28).

Pro-slavery Christians picked out isolated verses while ignoring the Bible’s grand narrative of liberation. In reality, the Old Testament is filled with the cry of the oppressed and God’s rescue. The God who commanded humane treatment of slaves (Ex. 21:16, 26–27), who brought the Israelites out of Egypt (Ex. 3:7–8), and who proclaims Himself “the Savior of the oppressed” (Isa. 58:6–7) cannot endorse the chattel slavery of his image-bearers. The gospels complete this picture: Jesus was sent “to proclaim liberty to the captives” (Luke 4:18) and he repeatedly defied the racial and status barriers of his day. The New Covenant known to Paul and the apostles is built on the great reversal that the last shall be first (Matt. 20:16) and that “in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free…for you are all one” (Gal. 3:28). When slaveholders used verses like “servants, obey your masters” as literal commands for race-based slavery, they ignored the context of mutual love and transformed power. St. Paul himself kept a runaway slave (Onesimus, Philemon 1–25) but never suggests slavery is a right; instead he recognizes that God’s gospel overturns every division.

The Higher Law of God: As Frederick Douglass observed, there is a world of difference between “the Christianity of this land” and “the Christianity of Christ.” In the appendix to his autobiography, Douglass wrote: “Between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference… I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding… Christianity of this land” . Douglass had witnessed that slaveholders claimed Jesus while trampling the weak. He saw that their “Christianity” denied the brotherhood of man and made God a respecter of persons. The Gospel of Christ, by contrast, “denies his fatherhood of the race, and tramples in the dust the great truth of the brotherhood of man,” he thundered . Indeed, Jesus calls us to a higher law than imperial obedience. When unjust masters demanded obedience as slaves (Ephesians 6:5), Jesus would turn it upside down by freeing believers from spiritual bondage (John 8:36) and by warning all Christians that true faith honors the image of God in every person. The Old Testament’s “curses” and New Testament household codes were descriptive of human sin, not a divine endorsement of racism and involuntary servitude. Honest Christianity rejects slavery as an offense to the Gospel and to God’s universal kingdom.

Hope in Exodus: In the slave cabins and hidden prayer meetings of the South, the Exodus story gave enslaved African Americans living hope. The Bible began to them “with the bondage of God’s people,” as Sojourner Truth noted: God heard the groaning of Israel in Egypt and “came down to deliver” them . Spirituals like “Go Down, Moses” expressed faith that God sees Black bondage and will one day say, “Let my people go.” Even amid chains and whips, enslaved mothers would teach children Exodus parallels — as Harriet Beecher Stowe later recognized, Uncle Tom was a figure Christlike in patience and sacrificial love. The prophets’ longing for a day when “each man will sit under his own vine and fig tree, with none to make him afraid” (Micah 4:4) became real vision for Black congregations. The promise “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (John 8:32) echoed in hymns and sermons. The escaped slave and famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass likewise drew on the Exodus motif: he spoke of “our Moses,” of God’s judgment on Pharaoh (slave masters), and even recalled how he read Moses’ serpent on the pole and longed for similar salvation. In his own Narrative he contrasts the religion of Christ with that of slaveholders, showing how slaves clung to the trueGospel in secret praise. As Douglass wrote in his later Fourth of July speech, the slaveholding religion “makes God a respecter of persons” and divides humanity into “tyrants and slaves” . Black preachers and communities pointed to Jesus and Moses to sustain them: Jesus freed Leviathan-ed sinner, and the suffering Christ understood their pain. In those humble cabin Bible-studies (as Winslow Homer captured in Sunday Morning in Virginia), faith became the crack in the wall of their prison, the sluice of hope in a dark age.

llustration: Winslow Homer’s “Sunday Morning in Virginia” (1877) shows enslaved family members gathered around a Bible. Despite brutal oppression, many slaves learned to read Scripture and sang spirituals, finding in the Moses story and Jesus’s words the promise of deliverance (Ex. 3:7–8; Luke 4:18). Frederick Douglass later contrasted this true Christianity with the “corrupt, slaveholding” mock-religion of his masters

As Black spirituality simmered beneath the surface, Northern and British revivalism kept the abolition flame alive. Preachers like Charles Finney thundered in upstate New York that slavery was not a benign institution but a “sin”demanding urgent repentance . Finney declared that anyone who persisted in slaveholding could not rightly join the church: “If I do not baptize slavery by some soft and Christian name, if I call it SIN… its perpetrators cannot be fit subjects for Christian communion and fellowship.” Garrisonian abolitionists took such convictions further. William Lloyd Garrison, founder of The Liberator, renounced politics (“No Union with Slaveholders”) and believed the Constitution itself was a pro-slavery pact. He famously proclaimed it a “covenant with death…an agreement with Hell,”refusing to support any government that protected slavery . In dramatic protest, Garrison read those words aloud and burned copies of the Fugitive Slave Act and even the Constitution on July 4, 1854 . “I will not equivocate, I will not excuse… I will be heard!” he proclaimed , signaling that no voice in Christendom should be silent on injustice. William Lloyd Garrison and the “radical abolitionists” he inspired saw the Gospel as irreconcilable with slavery – and many ministers and former slaveholders became fiery abolitionists.

Abolitionist women also wielded faith and Scripture. Harriet Beecher Stowe, daughter of minister Lyman Beecher, conceived Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a divinely inspired witness. She always insisted “God wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” awakening hundreds of thousands to the immorality of slavery . Sojourner Truth – herself an ex-slave converted to Methodism – traveled the land preaching and relating the slave’s plight to Scripture. In rallies she echoed Genesis’ cry and Isaiah’s vision of broken chains. At one Fourth of July oration (1851) she declared, “the promises of Scripture were all for the black people,” and reminded her audience that Abel’s blood cries out to heaven for justice . Frederick Douglass, who studied in secret by stealing his master’s books, became a fiery prophetic voice too. He republished his Narrative with an appendix that scorned the country’s Christianity: “I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding… Christianity of this land.” Douglass and others forced American Christians to look at the glaring contradiction between Gospel truth and slave law, pressuring churches to repent.

Biblical Foundations of Freedom and Equality: Abolitionists and Black Christians pointed to many scriptural principles that demanded justice. Galatians 3:28 taught that in Christ all people are one blood – there is no “slave” caste in God’s Kingdom. Exodus 3:7–8 is rehearsed at every reminder that God saw Israel’s slavery and promised, “I have come down to deliver them.” Isaiah 58 condemns superficial piety and declares that true fast and worship includes loosening the chains of injustice and letting the oppressed go free. Luke 4:18–19 quotes Isaiah to describe Jesus’ mission as proclaiming liberty to captives. St. Paul says bluntly, “Were you called while a slave? Do not be concerned about it; but if you can become free, avail yourself of the opportunity” (1 Cor. 7:21) – a theological jab at complacency. Jesus famously says, “If the Son makes you free, you will be free indeed” (John 8:36), applying ultimate spiritual freedom to every believer. Amos 5:24, a prophetic demand that “let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream,” rallied believers who saw the tearing of families and bloodshed in slave chases. These verses and others undergirded the case that slavery violated God’s intent for “justice, mercy, and faithfulness” (Micah 6:8) and betrayed the command to love one’s neighbor (Matt. 22:39), for Christ’s yoke is meant to be light, not to crush the oppressed.

A Nation Transformed: The Civil War and Emancipation came partly out of this moral and religious struggle. President Abraham Lincoln, a devout if self-educated Christian, often appealed to American ideals rooted in the Bible. In proclaiming freedom to the slaves, he echoed Exodus imagery: “Upon this act…may the angels of God have charge,” he said, invoking the great providential deliverance. After the war, Congress debated amending the Constitution to outlaw slavery altogether. The resulting 13th Amendment was more than a legal fix – it was a partial fulfillment of the Declaration’s dream that “all men are created equal, endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights”. Many Americans at the founding had seen that phrase as a reflection of biblical anthropology (Imago Dei) and the teaching that “God created man in His own image” (Gen. 1:27). In the 19th century, that principle undergirded abolitionist sentiment: the “rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” were seen as God-given, not to be ceded by any earthly power. When Lincoln pushed the 13th Amendment through Congress in 1865, he understood it as a step toward realizing the Nation’s “new birth of freedom.” Frederick Douglass and other black leaders argued that America would be hypocritical if it professed Christian and Enlightenment ideals yet kept millions as property. By abolishing slavery, the country at last legally embraced (however imperfectly) the moral truth that had long been told in Scripture: every human life has dignity and must be free.

Honest Lament and Redemptive Hope: The story of slavery in America is sobering. Christian people committed and tolerated terrible sins in God’s name. Yet history’s true verdict lies in the higher counter-witness of Scripture and in how some believers of the Second Great Awakening rose to meet the moment with courage and compassion. We acknowledge with grief that in antebellum America the “popular church” became, in Douglass’s words, “a huge, horrible, repulsive form” full of self-justification . But even amid lament we rejoice that Scripture’s ultimate vision prevailed: a new creation in Christ (Gal. 6:15) in which “there is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, male and female” (Gal. 3:28). The very rhetoric of equality in the founding documents found its engine in biblical moral teaching. As Mark Noll has observed, the Civil War was a “theological crisis” precisely because Americans of faith had failed to distinguish the Bible’s teaching on race from its record of racialized slavery . After abolition, systemic injustice persisted, but the prophetic voice of the Gospel (as Amos 5:24 declares) continued to call the nation toward God’s justice.

Today we continue to carry both lament and hope. We grieve that Christians so often fell short, yet celebrate how the trueChristianity of Christ – rooted in love, equality, and freedom – inspired a movement that reshaped our nation. The Scriptures promised “a kingdom that cannot be shaken” (Heb. 12:28), and in that higher kingdom we see the seed of America’s transformation. By the light of Scripture we recognize that all slavery is sin, and that the gospel leads people out of darkness into marvelous light. As heirs of this legacy, we must never stop praying, witnessing, and working for justice – for every enslaved heart, every oppressed soul, and every marginalized brother or sister. For the same God who split the sea and rose the Son up from the dead can liberate our nation and ours hearts too. We bind together the promise of Advent’s “new creation” with the humility of Good Friday, knowing that the blood of Abel has cried out but also that Christ’s blood has reconciled the nations. May the vision of Amos and Isaiah, of Jesus and Paul, continue to lead us to fullness of life and freedom for all.

References

Douglass, F. (1845). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office.

Douglass, F. (1852, July 5). What, to the slave, is the Fourth of July? (Speech, Rochester, NY).

Finney, C. G. (1852). Lectures on revivals of religion (Lecture XV). New York: A.S. Barnes.

Garrison, W. L. (1831, Jan. 1). Letter to the Public. The Liberator.

Noll, M. A. (2006). The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Rae, N. (2018, Feb. 23). How Christian slaveholders used the Bible to justify slavery. TIME. Retrieved from https://time.com/5171819/christianity-slavery-book-excerpt/

Stowe, H. B. (1852). Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Boston: John P. Jewett & Company.

Finkelman, P. (2000). Garrison’s Constitution: The Covenant with Death and How It Was Made. Prologue Magazine, 32(4). Retrieved from National Archives website.

Want to explore further?

Dig Deeper in to Civic Theology