Part 2 of Civic Theology: How the Bible Shaped America’s Founding and Freedom

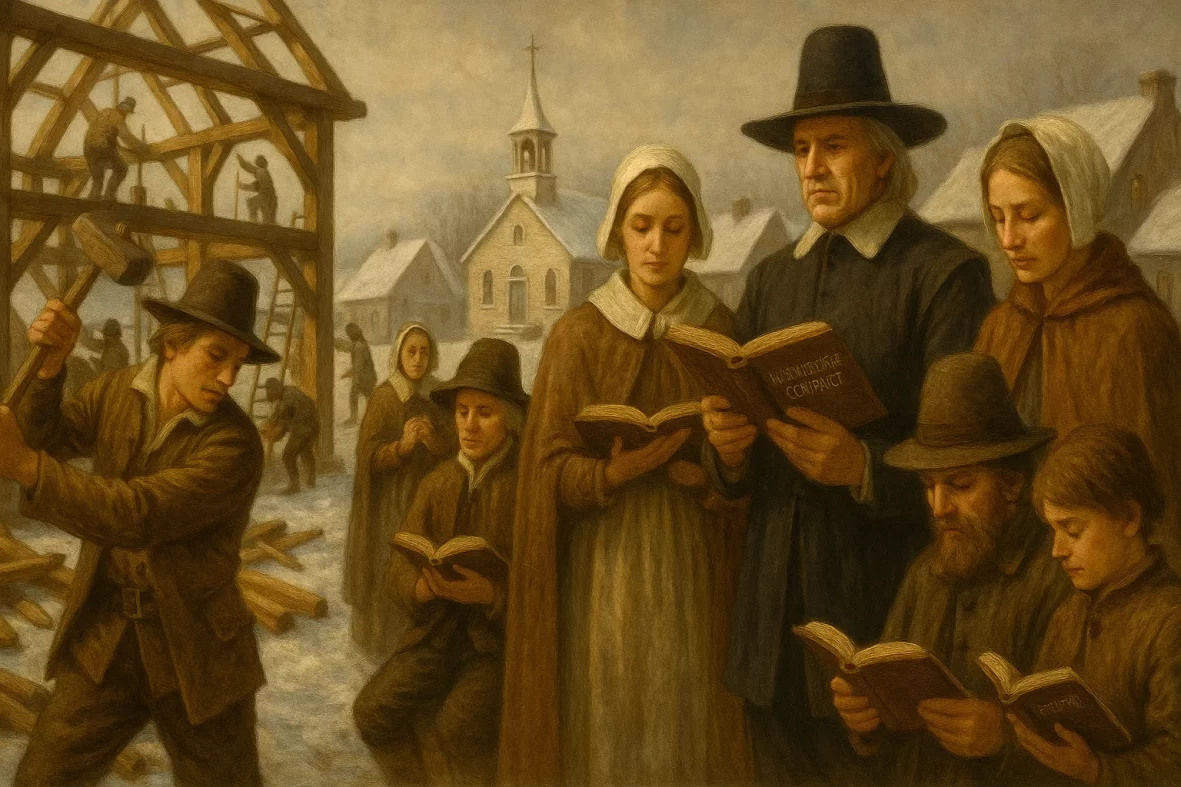

In the bitter cold of December 1620, a ragged band of Pilgrims huddled on the deck of the Mayflower, praying that God would preserve them through a treacherous Atlantic storm and into an unknown wilderness. Far from mere adventurers, these English Separatists believed they were on a divine mission: they were establishing a “plantation” under God’s eyes and by God’s covenant. Their compact aboard ship made this explicit: “Having undertaken for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith…to plant the First Colony…[we] do…mutually covenant and combine ourselves together in a Civil Body Politic” . This solemn pledge bound them not only to one another but to their sovereign Lord. In effect, the Mayflower Compact was America’s first covenant, a civil and spiritual bond set explicitly “in the presence of God”.

The Pilgrims’ vision was steeped in Scripture. They saw themselves as a new Israel, heirs of the Abrahamic covenant. God’s promise to Abraham – “I will establish my covenant between me and thee and thy seed…for an everlasting covenant” – echoed in their hearts as they huddled on the New England shore. To them, this promise now had a new chapter: a covenant people begotten not by physical blood alone, but by faith and obedience in a Promised Land of America. Later Puritan leaders would hark back to these texts. John Winthrop, aboard the Arbella in 1630, spoke of choosing life over death with Moses’ voice on his lips, citing Deuteronomy 30:19: “there is now set before us life and death, good and evil…to keep His commandments…and the articles of our covenant with Him, that we may live and be multiplied” . The Puritans believed these ancient words applied to their own settlement: if they obeyed God’s covenant-law, He would bless and multiply them; if they turned aside, they would invite judgment.

This covenantal outlook infused every facet of New England life. John Witte Jr. observes that Puritan divines considered the idea of covenant “the marrow of Puritan divinity” – even the “marrow” of their community . In seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay, the covenant was no mere theological abstraction but an organizing principle. As one Puritan minister proclaimed in 1624, “We are by nature covenant creatures…bound together by covenants innumerable and…bound by covenant to our God…Blest be the ties that bind us.” . In other words, God had fashioned human society itself as a web of sacred agreements. Each church-member’s promise to walk in Christ’s ways was a covenant; each town’s agreement to order itself according to God’s Word was a covenant; even the king’s authority was understood as delegated under God’s covenant-law. As later Puritan leaders taught, “all authority, rightly understood, was derived from God, and all rulers…were merely His agents”, charged with enforcing divine law in the world . In the Puritan mind, civil law had to mirror biblical law; moral order flowed from God’s will. As one analysis puts it, divine law was “the animating force for positive law” in New England, “the principal source of human liberty” and the necessary boundary that kept freedom from becoming license.

Covenants of Community:

Plymouth and Boston

From Plymouth Rock to Boston’s Common, Puritanism meant covenant in practice. The very first charter – the Mayflower Compact – opened “In the name of God, Amen” , and declared that the new colony would enact just and equal laws “for the general good” by mutual consent. In framing government as a solemn bond before God, the Pilgrims explicitly echoed the language of Biblical covenants. They “covenanted and combined ourselves together in a Civil Body Politic” – a concrete act of collective faith. As the Religious Freedom Institute notes, this was no Enlightenment social contract, but a theological one: the key word was literally “covenant,” drawn from the Bible and the Separatist tradition . These early settlers gathered not just for trade or land, but for God’s glory. William Bradford’s record of the Compact shows them stating boldly that they undertook the voyage “for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith” – a phrase almost lifted from Isaiah or Psalms, not Hobbes or Rousseau.

Less than a decade later, John Winthrop carried this vision further. In his famous “Model of Christian Charity” sermon (1630), delivered before reaching New England’s shores, Winthrop painted an epic mission for his people. Citing the biblical distinction of Israel as a “holy nation,” he urged his flock to become “as a city upon a hill” under God . They were onstage for the watching world: “The eyes of all people are upon us,” he warned, so that if they broke faith, “we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world” . His imagery could hardly be plainer – New England was God’s marquee display of redeemed society, meant to shine His light.

Winthrop’s sermon was saturated with covenant theology. He finished by quoting Moses on the plains of Moab, where God told Israel: “Behold, I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing…choose life, that thou and thy seed may live” . Winthrop applied this challenge to Massachusetts Bay: as he admonished, they must love God, keep His commandments, and honor the “articles of our covenant” if they would receive blessing in the new land. If instead they broke that covenant – by greedily pursuing their own pleasure or worshiping other gods – Winthrop warned, God would turn away: “we shall surely perish” . Such stark terms show how intimately Puritans tied their future to covenant faithfulness. Winthrop cast the colonial venture in overtly biblical colors – it was a New Israel, bound by covenant to a covenant-keeping God.

Even beyond sermons and charters, colonial institutions echoed covenantal ideas. Congregational churches drew up written covenants that each member signed. One typical covenant (Salem, 1629) began: “We Covenant with the Lord and one with another…to walk together in all His ways, according as He is pleased to reveal Himself unto us in His blessed Word of truth.” . These church covenants explicitly bound believers together under Scripture. Another clause avowed, “We avouch the Lord to be our God, and ourselves to be His people” – language straight from Leviticus. In short, each Plymouth or Boston church was a self-governing “body politic” of saved souls, each member binding himself to the others and to God in the solemn presence of the Word and the church. Non-compliance could mean removal from membership, which in Puritan society meant loss of civil rights too. Thus ecclesiastical covenants reinforced the civic covenants: both spheres operated under God’s law and mutual accountability.

Law codes, too, wore Scripture’s imprint. In 1641 Massachusetts codified the Body of Liberties, its first legal code. While promoting many rights, it was explicit that law should reflect “the Word of God.” For example, capital offenses in Massachusetts often came from Old Testament prescriptions . The General Court itself, on several occasions, instructed committees to frame laws “agreeable to the Word of God, which might be the fundamentals of this Commonwealth” . In practice, this meant blue laws against Sabbath-breaking, swearing, and immorality – all enforced by church courts. Puritan judges and magistrates often preached that English common law was meaningless if it strayed from divine law. As an Acton Institute study notes, Puritans saw positive (civil) law as animated by divine standards; “divine law was the principal source of human liberty” in their view . In short, the civic order was nothing less than God’s commonwealth on earth.

What held this theocratic society together was the notion of mutual obligation. Each town and church was essentially a covenant among brethren under God. Everyone was accountable to everyone else. If an individual sinned, it could bring communal shame. If the community prospered, it was a sign of divine favor. Jonathan Edwards, preaching after the great 1727 New England earthquake, made this explicit: disasters and blessings were national signs tied to covenant faithfulness . In one sermon he warned his parish that “if a nation or people are very corrupt and remain obstinate…God will not suffer a people that grow very corrupt…to go unpunished in this world” . In Edwards’ federal theology, God often lets wicked individuals flourish, but as a people He only deals in earthly rewards and punishments. The glib lesson: New England must repent, or risk God’s withdrawal. At the same time, Edwards reminded them of God’s mercy: as long as they honored their covenant, they would enjoy divine protection and “temporal blessings” like fertility and peace . In short, corporate blessing and curse – a core theme of Deuteronomy – underpinned New England’s political and spiritual life.

Puritan preachers thus used Old Testament patterns constantly. They spoke of themselves as God’s “holy nation” (quoting Exodus 19:6), and regularly cited Micah 6:8, the prophet’s challenge to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God. In fact, later writers noted that this one verse was “the essence of the law, the spiritual side of it” . To Puritans, Micah’s call was not optional piety but civic duty. A godly community must be marked by charity, righteousness, and humility before God. The Boston and Cambridge leaders aimed to weave these virtues into every ordinance, every sermon, and every act of daily life. In their ideal, a child learned Micah 6:8 at the family dinner table and saw it reflected in the town meeting’s resolve to clothe widows and punish oppressors alike. By walking “humbly” with God (Micah 6:8), the whole community proved its covenant fidelity.

City on a Hill:

Covenant and American Destiny

This Puritan vision – a covenant community under God – left an indelible mark on America’s civic theology. As historian Perry Miller once noted, unlike other nations that “grew up by chance,” New England had “a recorded past – a written and articulate beginning” in its charters and sermons . Winthrop’s sermon and other texts became touchstones for later generations seeking America’s purpose. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Americans frequently invoked that “city on a hill.” President Kennedy quoted Winthrop when he came to Boston, and President Reagan later dubbed the country itself “a shining city upon a hill.” Stout observes that we still live in “a world formed largely by the Puritans and [Edwards],” because Americans have long understood their nation in covenantal terms . The idea that America has a divine mission – to be a light of liberty or to spread democracy – owes much to the Puritan impulse.

Even beyond the pulpit, American leaders echoed Puritan imagery. In the Civil War era, Abraham Lincoln looked to Israel for inspiration. He spoke of the Union’s cause as more than “national independence…something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world” . In Trenton, he referred humbly to “the Almighty” and described Americans as “his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle” . Lincoln’s language – carrying Moses’ mantle, being an instrument of God – shows the lingering spirit of Puritan covenant theology in American public life.

Likewise, the very idea of being “one nation under God” in the Pledge or having an “in God We Trust” on coins reflects the old conviction that the United States was under a divine mandate. As one scholar puts it, founding Americans read the Bible’s stories of covenant peoples and applied them to themselves . They may not have imposed Puritan laws on a secular republic, but their inherited worldview made them receptive to the notion that liberty itself is a trust from heaven. The Constitution’s appeal to “Nature and Nature’s God,” the Declaration’s “Creator,” and even Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (“under God, this nation shall have a new birth of freedom”) all resonate with that Puritan sense of history under providence.

In short, the Puritan covenant community planted the seed of American civil religion. Every Massachusetts meetinghouse and Plymouth pulpit was, in effect, preaching that this New World settlement was a colony of heaven. Their Biblical vision was one of mutual accountability (Romans 14:13; “lest we be judged…each shall give account”), just government (“render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” and also God’s law), and collective destiny (“they shall be a nation to the Lord,” Exodus 19:6). These beliefs did not vanish when the republic was born; rather, they shaped the young country’s story. Today, we still hear echoes of Winthrop’s covenant when Americans talk of a “shining city,” a “nation of laws under God,” or a people “chosen” for liberty’s sake.

Walking Humbly Together

We might summarize: Puritan New England was, above all, a covenant community – a people who believed their civic life was bound by sacred promises. As John Witte Jr. concludes, covenant law in New England expanded to embrace almost every sphere of life . The Pilgrims’ Compact, the Bay Psalm Book, the Body of Liberties, Winthrop’s sermon, and the endless sermons at Faneuil Hall all testified to a single truth: history was going on under God’s supervision, and Americans were participants in God’s covenant plan. They believed that God’s blessing depended on obedience (Jer. 11:3‑5; Deut. 28) – a doctrine taken so seriously that Jonathan Edwards preached earthquakes as covenantal warnings . They held that a people united by faith could do great things: by “the love among [them]…the world may know they are a people that believe on [God]” (John 13:35), as one New England clergyman paraphrased.

And so the Puritan picture of America endures: a nation under God, with a moral commission. It is a theme of blessing if we keep covenant, and judgment if we forget it. To “walk humbly with God” (Micah 6:8) – to obey justice, love mercy, and walk humbly – was for the Puritans the key to civic virtue . These pilgrims in spirit believed their country’s fate hung on this divine principle, and their idea of covenant-shaped commonwealth still calls each generation to the same choice of life or death, blessing or curse . In our time, remembering their covenant may not make us a theocracy, but it reminds us of a foundational truth: America’s identity was born in a Bible open to the sky, under which a covenant people vowed to make her blessings of liberty overflow.

References: All quotations and historical facts above are drawn from primary Puritan sources and scholarly studies. For example, John Winthrop’s original 1630 sermon is available at the Gilder Lehrman Institute , and William Bradford’s journal printed the Mayflower Compact . Scholarly works documenting Puritan covenant theology include Witte’s “Covenant and Community in Puritan Thought” and Stout’s “The Puritans and Edwards.” Contemporary analyses (e.g. Patterson & Blessing on the Compact , Acton Institute on Puritan political ideas ) and Spurgeon’s exposition of Micah 6:8 show the continuity of these themes. (For brevity we have cited them in the text as shown above. A full APA-style list of all referenced works follows.)

Reference List

- Gilder Lehrman Institute. (2012). A Model of Christian Charity (John Winthrop, 1630) . Retrieved from https://www.gilderlehrman.org

- Patterson, E., & Blessing, R. (2021, Nov. 11). America’s Theological Social Contract: The Mayflower Compact . Religious Freedom Institute. https://religiousfreedominstitute.org

- Spurgeon, C. H. (1889). Micah’s Message for Today (Commentary on Micah 6:8) . In Spurgeon’s Verse Expositions of the Bible (Vol. 36). (Available at StudyLight.org)

- Stout, H. S. (1985). The Puritans and Edwards. Christian History Magazine, 8. (Republished online by CHI)

- Witte, J. (1987). Blest be the ties that bind: Covenant and community in Puritan thought. Emory Law Journal, 36, 579–615 .

- “Covenants of New England (1629–1639).” (n.d.). A Puritan’s Mind. Retrieved [access date], from https://apuritansmind.com/creeds-and-confessions/covenants-of-new-england/

- Smith, S. A. M., & Smith, B. A. (2025, Jan. 6). The Puritan as Governor: With the Consent of the Governed. Religion & Liberty Online (Acton Institute) .

- Strand, P. (2024, July 3). America’s ‘Explicit Covenant with God’: How a nation pledged to God can save a world or lose it. CBN News.

- Van Engen, A. (2020). How America became “a city upon a hill”: The rise and fall of Perry Miller. Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, 41(1).

- Soloveichik, M. Y. (2021, Feb. 1). Lincoln’s Almost Chosen People. First Things.

Want to explore further?

Dig Deeper into Civic Theology