What the Nazareth Inscription Can—and Cannot—Tell Us About the Resurrection

I saw this on Facebook.

Which, as a general rule, is a sentence that should cause historians, pastors, and anyone who has ever footnoted a claim to pause, take a breath, and maybe refill their coffee.

The post was confident. Bold. Sharply worded. It claimed that Rome issued a death decree because of Jesus’ empty tomb, and that history “can’t explain it away.” The evidence? A marble inscription known as the Nazareth Inscription, now housed in the Louvre, warning that anyone who removed a body from a sealed tomb would face capital punishment.

At first glance, it’s a striking claim. And to be fair, it touches something real. The resurrection of Jesus was not preached as a private spiritual experience or a poetic metaphor. It was proclaimed as a public event, tied to a real tomb, in a real place, at a real moment in history. And from the very beginning, that claim caused trouble.

So I understand why a post like this resonates. Christians are tired of hearing that the resurrection is a fairy tale, a legend that grew over time, or a story meant only for personal comfort. The instinct behind the post is right. Something happened, and it mattered.

But as Paul Harvey used to say, “And now… the rest of the story.”

History, especially ancient history, is rarely as tidy as a viral paragraph. Stones do not speak in headlines. They whisper in context. And if we want to honor both the truth of the resurrection and the integrity of history, we need to slow down, look carefully, and ask what this Roman decree can tell us—and just as importantly, what it cannot.

That’s what this article is about.

Not debunking faith. Not hyping evidence. But walking carefully through a stone, a tomb, and the world that took both very seriously.

The Stone in the Louvre

What the Nazareth Inscription Actually Is

Before we decide what the Nazareth Inscription means, we need to be clear about what it is. History has a way of punishing us when we skip that step.

The Nazareth Inscription is a marble slab, roughly two feet tall, inscribed in Greek with what reads like a formal Roman legal decree. Today it sits in the collections of the Louvre Museum, where it is cataloged not as a Christian artifact, but as a piece of Roman epigraphy. In other words, this is not a church relic. It is a government warning, carved in stone.

The text itself is blunt. It forbids the disturbance of tombs and the removal of bodies, and it threatens severe punishment, even death, for those who violate graves “with wicked intent.” This is not about stealing grave goods. The concern is the body. Whoever commissioned this decree wanted that point to land hard.

The inscription entered modern scholarship in the late nineteenth century. In 1878, it was acquired by Wilhelm Froehner, a respected classical scholar and epigrapher working in France, who later donated it to the Louvre. Froehner reported that the stone came from Nazareth, which is how it received its now-famous name. That reported origin would later become a point of debate, but at the time, it was simply recorded as part of the artifact’s acquisition history.

A word about Froehner is worth saying here. He was not an apologist hunting for proof texts. He was a careful nineteenth-century antiquarian doing what scholars of his era commonly did: acquiring, cataloging, and preserving inscriptions before they disappeared into private hands or were lost altogether. There is no evidence that he saw this stone as explosive or even particularly unusual. He treated it as a Roman decree and moved on.

That restraint has proven instructive.

From a scholarly standpoint, the inscription is widely regarded as authentic. The Greek language fits the eastern Roman world. The letter forms align with early imperial usage. The legal tone matches other known Roman edicts. While scholars debate its precise date, most place it somewhere in the early Roman imperial period, broadly within the first century.

So at the most basic level, we can say this with confidence. The Nazareth Inscription is not a medieval forgery. It is not a Christian invention. It is not a legend that grew up around the Gospels. It is a real piece of Roman law, preserved in stone, addressing a problem Roman authorities took seriously.

That alone makes it worth our attention.

But stones, like texts, do not interpret themselves. Before we ask whether this decree has anything to do with Jesus or the resurrection, we need to ask a more modest question first. Why would Rome feel the need to say something like this at all?

That’s where things begin to get interesting.

Why This Decree Is Unusual (But Not Magic)

At this point, it’s tempting to lean forward in our chairs and say, “Aha.” A Roman decree. A death penalty. Tombs. Bodies. Surely this must be something extraordinary.

It is unusual. But it’s not magic. And learning to hold those two ideas together is part of thinking historically.

Rome did have laws about tombs. That part is not surprising. Graves were considered protected spaces across the empire. Disturbing them could violate family honor, civic order, and religious sensibilities. Grave robbing, especially the theft of valuables buried with the dead, was a known problem. Roman law addressed it regularly.

What makes the Nazareth Inscription stand out is not that it protects tombs, but how it does so.

First, the focus is not on property.

Most Roman burial laws are concerned with stolen goods, damaged monuments, or unauthorized reuse of burial space. This decree zeroes in on the removal of the body itself. The language is moral as much as legal. The offense is framed as wickedness, not merely theft. That is a narrower concern, and a more charged one.

Second, the severity of the penalty is striking.

Threatening death for tomb violation is not the Roman default. Fines, restitution, and local penalties were far more common. Capital punishment signals that whoever issued this decree believed the offense was not just disrespectful but socially dangerous. Rome did not escalate penalties unless it thought order itself was at stake.

Third, the tone feels preventative rather than routine.

This does not read like a response to a one-off crime. It reads like a warning meant to stop something from happening again. Rome was very good at this kind of governance. When it perceived a behavior as destabilizing, it didn’t wait for motives to be sorted out. It deterred the act itself, decisively and publicly.

At the same time, there are important things this inscription does not tell us.

It does not name a specific incident.

It does not mention a particular city, tomb, or individual.

It does not identify the emperor who authorized it.

And it does not tell us how widely it was posted or enforced.

That means we have to resist the urge to let the stone answer questions it was never carved to address. History is not impressed by our conclusions. It only gives us what it gives us.

So where does that leave us?

The Nazareth Inscription is unusual because it treats the removal of bodies from tombs as a grave threat to public order, worthy of the harshest deterrent Rome could apply. That tells us something about the kind of fears and pressures Roman authorities faced in parts of the empire.

What it does not do is tell us why, in this specific case, Rome felt compelled to act.

To answer that, we have to widen the lens. We have to ask what kinds of claims, rumors, or controversies could make an empty tomb more than a religious curiosity.

And for that, we need to listen to the sources that describe the world where this decree would have been read.

The Empty Tomb in the Gospels

A Public Problem, Not a Private Vision

When the New Testament introduces the resurrection, it does not do so quietly. There is no sense that this was meant to be a private spiritual insight, tucked safely away from public scrutiny. The Gospels present the resurrection as a claim that immediately collided with authorities, rumors, and competing explanations.

That is especially clear in the account preserved in the Gospel of Matthew.

Matthew tells us that after Jesus was buried, the chief priests and Pharisees went to Pilate with a concern. They remembered Jesus’ prediction that He would rise, and they asked for the tomb to be secured “lest His disciples come and steal Him away” and spread a worse deception than the first. A guard is posted. The tomb is sealed. In other words, the authorities themselves frame the problem in advance as one of body removal.

After the tomb is found empty, Matthew records what happens next. The guards report what they have seen, and a counter-narrative is immediately constructed. The explanation offered is not that Jesus survived the crucifixion, or that the women went to the wrong tomb, or that the disciples experienced visions. It is simple and concrete: “His disciples came by night and stole Him away while we were asleep.” Matthew then adds a telling detail, that this story “has been spread among the Jews to this day.”

That line is easy to read past, but it matters. Matthew is not inventing a tidy ending. He is acknowledging an ongoing public dispute. The resurrection proclamation did not go unchallenged. It was contested from the beginning, and the contest centered on what happened to the body.

The other New Testament writings assume the same landscape. In the book of Acts, resurrection preaching repeatedly provokes unrest, interrogation, and official concern. Roman authorities are rarely interested in sorting out theology, but they are very interested in crowds, accusations, and disorder. The resurrection message consistently creates all three.

Paul’s letters, written earlier than the Gospels, point in the same direction. When he insists in 1 Corinthians 15 that Jesus was buried and raised, and when he appeals to living eyewitnesses, he is not speaking in abstractions. He is grounding the claim in history that could, at least in principle, be checked. A resurrection that leaves a body behind would have been easy to silence. A resurrection tied to an empty tomb was not.

Taken together, the New Testament does something quietly important. It places the resurrection claim squarely in the realm of public knowledge and public controversy. Whatever one ultimately believes about the event itself, the texts assume that everyone involved agreed on at least one point: the tomb was empty, and that emptiness demanded an explanation.

That brings us closer to the world in which a Roman decree about bodies and tombs would make sense. Not as a theological response, but as an attempt to control a problem that had escaped the boundaries of private belief.

To understand just how sensitive that problem could be, we need to listen to a first-century voice outside the New Testament, someone who knew both Jewish burial customs and Roman anxiety from the inside.

Josephus and the World of Burial, Rumor, and Roman Anxiety

To appreciate why an empty tomb could become a public problem rather than a theological footnote, we need a guide to the first-century Jewish and Roman world who is not writing as a Christian. That guide is Flavius Josephus.

Josephus was a Jewish aristocrat, priest, and historian who lived through the turbulence of the first century. He wrote under Roman patronage, trying to explain Jewish life and history to a Greco-Roman audience. That makes him an especially valuable witness here. He is not defending the Gospels. He is describing the world they emerged from.

One of the things Josephus makes unmistakably clear is how seriously Jews took burial. In his writings, he notes that Jewish law required even those executed by the state to be buried before sundown. Bodies were not disposable. They were not props in political theater. Proper burial was a matter of obedience to the law of God and respect for the dead. Mishandling a body was not merely offensive. It was defiling.

That cultural reality matters. In a Jewish context, disturbing a tomb was not a niche crime. It struck at the heart of religious identity and communal order. A missing body would not simply raise questions. It would ignite outrage, speculation, and accusation.

Josephus also helps us see how Rome viewed situations like this. Throughout his histories, Roman officials appear less concerned with the finer points of belief and far more concerned with rumor, crowds, and unrest. Prophets, signs, and movements were dangerous not because of their theology, but because of their ability to mobilize people. Rome tolerated many beliefs. It did not tolerate instability.

Josephus records again and again that Roman responses escalated when stories spread faster than facts and when religious claims began to ripple through the population. In that kind of environment, authorities did not wait to determine who was right. They moved to suppress whatever behavior they believed was fueling disorder.

Put those two pieces together, and the picture sharpens. In a world where burial was sacred and rumor was volatile, allegations of body removal from a tomb were not a minor detail. They were a flashpoint. A claim that a body had been taken, whether framed as theft or resurrection, had the potential to disturb both religious sensibilities and civic peace.

Josephus does not mention Jesus’ empty tomb. He does not cite Roman decrees about graves. But he gives us something just as important. He shows us why bodies mattered, why stories mattered, and why Roman authority was always alert to anything that might turn belief into unrest.

Seen through that lens, a Roman warning carved in stone about disturbing tombs no longer feels abstract. It feels like something that belongs to this world.

Jewish and Pagan Pushback

The Body-Theft Story That Wouldn’t Die

One of the quiet tests of a historical claim is not how it begins, but how long its opponents feel the need to answer it. By that measure, the resurrection proclamation did not fade quickly. It provoked a response that had surprising staying power.

Matthew hints at this when he notes that the explanation about the disciples stealing the body was still being circulated “to this day.” That line opens a window into an ongoing public argument, not a settled dispute. And when we look beyond the New Testament, we find that the same basic charge continues to surface, long after the first witnesses were gone.

By the middle of the second century, early Christian writers are still responding to it. Justin Martyr, writing in his Dialogue with Trypho, refers to Jewish claims that Jesus’ followers took the body and deceived the public. Justin’s tone is defensive but revealing. He does not treat the accusation as novel. He treats it as familiar, something his readers would recognize.

A generation later, Tertullian alludes to similar mockery, including the suggestion that Jesus’ body was removed for mundane reasons, even jokingly attributed to a gardener protecting his produce. The humor cuts both ways. It shows ridicule, but it also shows that the debate still centered on the missing body, not on whether the tomb existed or whether Jesus had been executed.

By the late second and early third centuries, Origen is answering a pagan critic named Celsus. Celsus dismisses the resurrection as deception and fantasy, but again, the implied problem remains the same. Christians are accused of fabricating a story around a body that disappeared.

Even later Jewish tradition preserves echoes of this polemical instinct. References in the Babylonian Talmud, while compiled centuries after the events and treated with caution by historians, reflect a memory of Jesus framed as a deceiver whose followers led others astray. These texts are not first-century evidence, and they cannot be read as straightforward history. But they do show how Jewish counter-narratives developed. They deny the Christian claim not by conceding an empty tomb and explaining it away as insignificant, but by reinterpreting it as deception.

The pattern is what matters.

Across Jewish, pagan, and Christian sources, the debate keeps returning to the same pressure point. The body is gone. The explanation is contested. And the charge of theft or deceit refuses to disappear.

That persistence tells us something important. Whatever else one believes about the resurrection, the early argument was not fought on the ground of vague spirituality or private visions. It was fought over a tomb, a body, and competing stories about what happened to it.

By the time we reach the second and third centuries, Rome, Judaism, and Christianity are all responding in different ways to the same unresolved question. That is the historical backdrop against which a Roman decree about disturbing graves begins to feel less like an abstraction and more like a symptom of a deeper anxiety.

Now we are finally in a position to ask the question that started all of this. Where, if anywhere, does the Nazareth Inscription fit into this story?

So, Where Does the Nazareth Inscription Fit?

At this point, we can finally return to the stone itself, but now with better questions in hand.

If you read the Nazareth Inscription in isolation, it is simply a Roman warning about tomb violation. Severe, yes. Unusual, certainly. But opaque. Stones do not tell you why they were carved unless you already understand the world that carved them.

When you read the inscription within the world we have just traced, the picture sharpens.

Here is the most responsible way to frame the connection.

The Nazareth Inscription does not mention Jesus.

It does not name Christians.

It does not refer to Judea, Galilee, or Jerusalem.

It does not explain its own historical trigger.

Those limits matter. Any argument that ignores them is asking the stone to preach a sermon it never intended to deliver.

And yet, the inscription fits remarkably well with the kind of controversy the resurrection proclamation created.

Think about what we now know from the sources. The earliest Christian claim centered on a bodily resurrection tied to a specific tomb. The earliest rebuttal was not philosophical. It was procedural. Someone moved the body. That accusation circulated widely enough to require explanation, defense, and repetition for generations. Jewish burial customs made such a charge incendiary. Roman governance treated rumor-fueled unrest as a threat to order, not a matter for theological debate.

In that context, a Roman decree threatening death for removing bodies from tombs begins to look less abstract. It reads like an attempt to shut down a behavior at the center of a destabilizing dispute. Not because Rome cared about resurrection claims, but because Rome cared deeply about anything that turned belief into unrest.

This is where we need to be precise.

The Nazareth Inscription does not prove the resurrection.

It does not confirm the Gospel accounts.

It does not document a Roman investigation into Jesus’ tomb.

What it does is something subtler and, in some ways, more interesting.

It tells us that in the early imperial world, the removal of bodies from tombs was taken seriously enough to warrant the harshest possible deterrent. It tells us that authorities understood how explosive such claims could be. And it tells us that the kind of explanation Matthew records, the stolen body, was not the sort of thing Rome was content to leave to local rumor.

Put simply, the inscription functions like a pressure gauge. It does not tell us exactly where the pressure came from, but it tells us that the pressure was real.

And that is where many viral arguments go wrong. They rush from “this fits” to “this proves.” History almost never rewards that leap. But it does reward careful convergence. When independent sources, written for different reasons, begin to illuminate the same fault line, historians take notice.

The Nazareth Inscription belongs at that level. Not as a smoking gun, but as part of the background noise of an empire trying to keep order in a world where an empty tomb had become everyone’s business.

Before we draw conclusions, however, there is one more complication we need to face honestly. Stones come from somewhere. And where this stone likely came from affects how tightly we can connect it to the events in Judea.

That brings us to the question of location, marble, and why historians refuse to let us skip over either.

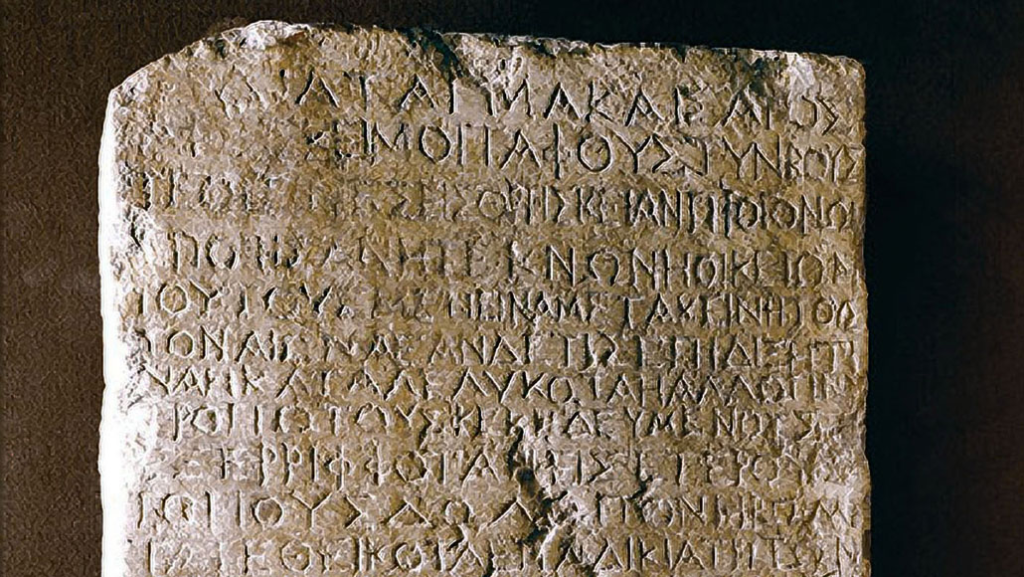

Why Location and Marble Still Matter

By now, some readers are probably wondering why scholars keep circling back to a detail that feels almost pedantic. If the decree came from Rome, and if Roman marbles were traded across the empire, why does it matter where this particular slab was quarried or first displayed?

The short answer is that historians care about where authority shows up, not just where it originates.

Imperial decrees did not appear everywhere at once. Rome governed through selective visibility. Laws were sent out, but they were carved in stone and posted where officials believed they needed to be seen. A marble inscription tells us not only what Rome said, but where someone thought it mattered enough to say it publicly.

That is why the question of provenance matters.

The Nazareth Inscription is traditionally associated with Nazareth because Wilhelm Froehner recorded that as its source when he acquired it in the nineteenth century. If the stone truly stood in or near Galilee, then it would be reasonable to ask whether local controversies, including resurrection claims, shaped its deployment.

But modern scientific analysis complicates that picture. Studies of the marble itself suggest it likely originated near Kos, an island in the Aegean Sea. That does not automatically tell us where the inscription was posted, but it does shift the balance of probability. Transporting heavy stone over long distances was possible, but it was not routine for functional legal notices. Stones tended to stay closer to the civic worlds that commissioned and displayed them.

And that civic world matters. Kos was a Greek-speaking city with its own burial customs, local disputes, and public spaces where imperial authority was made visible. If the inscription belonged there, historians are obligated to ask whether tomb violations, hero cult disputes, or other local concerns in the Aegean world better explain the decree’s presence than events in distant Judea.

This is not an attempt to explain the resurrection away. It is an attempt to keep history honest.

Roman marbles did travel, and stones were reused, repurposed, and relocated. But provenance is one of the few tools historians have to narrow possibilities rather than multiply them endlessly. A text without a place can mean almost anything. A text anchored, even loosely, to a place can mean fewer things, and those meanings are sharper.

So the responsible conclusion here is not “this has nothing to do with Jesus,” nor is it “this proves Rome reacted to the resurrection.” It is something more modest, and more durable.

The Nazareth Inscription tells us that Rome treated corpse removal as a serious threat in parts of the eastern empire. Where exactly that concern crystallized remains debated. What is not debated is that the issue itself was volatile enough to warrant imperial attention.

Stones, like history, rarely cooperate with our desire for tidy conclusions. They force us to weigh probabilities, not chase certainties. And when we do that patiently, we are left not with less meaning, but with a more trustworthy one.

With that final complication on the table, we can step back and ask the bigger question. When all of these sources are read together, what kind of pattern actually emerges?

The Pattern That Emerges

When All the Sources Are Read Together

When we finally step back from the details and read all of these sources side by side, something steady and coherent comes into view. Not a single, decisive piece of evidence that answers every question, but a pattern of convergence that history rarely produces by accident.

Start with the New Testament. The resurrection of Jesus is proclaimed early, publicly, and bodily. The tomb is known. The authorities are involved. And the earliest rebuttal is not denial of death or confusion about location, but the accusation that the body was removed. From the beginning, the debate turns on what happened to the corpse.

Add Josephus. He shows us a Jewish world in which burial was sacred and mishandling the dead was a serious offense, not a symbolic misstep. He also shows us a Roman world that was constantly alert to movements, rumors, and stories that could ignite unrest. Belief was not Rome’s concern. Stability was.

Then layer in Jewish and pagan polemic. Across generations, critics of Christianity keep returning to the same explanation. Deception. Theft. Fabrication. The accusation evolves in tone and detail, but the center of gravity remains the same. The body is gone, and Christians are accused of making something of it that should not be believed.

Finally, place the Nazareth Inscription into that world. Not as a proof text, but as a contextual signal. Here is Rome, warning in the strongest possible terms against removing bodies from tombs. The decree does not tell us why it was issued or where it was first displayed. But it tells us something important about what Rome feared. Corpse removal was not a private matter. It was a public threat.

Each source speaks with its own voice.

Each has its own agenda.

Each is written for a different audience.

And yet, they all illuminate the same fault line. Bodies matter. Tombs matter. Stories about missing bodies matter even more.

This is where historical reasoning earns its keep. No single source demands belief. But when independent witnesses converge on the same pressure point, historians take notice. The resurrection proclamation did not arise in a vacuum of myth-making or private spirituality. It emerged in a world primed to react, argue, deny, and legislate.

And that is the quiet strength of this pattern. It does not force a conclusion. It frames the question honestly.

The early Christian claim was not that Jesus lived on in memory or metaphor. It was that a tomb was empty, and that God had done something history could not ignore. Rome did not need to believe that claim to feel its impact. Judaism did not need to accept it to resist it. And Christians did not stop proclaiming it, even when the cost became clear.

Different sources. Different purposes. Same disturbance.

That is what the Nazareth Inscription ultimately contributes to the conversation. Not certainty, but context. Not proof, but pressure. And sometimes, in historical inquiry, that is exactly where the truth does its quiet work.

All that remains now is to return to where we began, and to ask what this means for how we read viral claims, ancient stones, and the resurrection itself.

Conclusion

And Now… the Rest of the Story

So let’s go back to where this began. A Facebook post. A bold claim. A stone that seemed to shout what Christians have always believed.

The instinct behind that post was not wrong. It sensed that the resurrection of Jesus was not a quiet, internal affair. It was a disruptive claim that entered history with force. It collided with authority. It provoked counter-stories. And it refused to go away.

Where the post ran ahead of the evidence is where most of us are tempted to run ahead of history itself.

The Nazareth Inscription does not tell us that Rome investigated Jesus’ tomb. It does not record an imperial panic over the resurrection. It does not prove that Caesar issued a decree because of Easter morning. Stones are stubbornly unwilling to make our arguments for us.

But the stone does tell us something important.

It tells us that in the early Roman world, the removal of bodies from tombs was taken seriously enough to warrant the harshest legal response imaginable. It tells us that authorities understood how destabilizing claims about missing bodies could be. It tells us that this was not the sort of controversy Rome left to theological debate or private opinion.

When you read the New Testament, Josephus, Jewish polemic, early Christian apologetics, and Roman law together, a consistent picture emerges. An empty tomb was not a curiosity. It was a problem. It demanded explanation. It generated accusation. And it forced institutions built on order to respond.

That matters for how we talk about the resurrection.

Christian faith does not rest on viral claims or clever connections. It rests on a historical proclamation that entered a real world of burial customs, political anxiety, and human resistance. The resurrection does not need exaggeration to be compelling. It is already strong enough to provoke denial, legislation, and centuries of debate.

So yes, history doesn’t issue death decrees over fairy tales.

But history also doesn’t hand us neat conclusions tied up in stone. It gives us context. Pressure points. Converging witnesses. And then it asks us to decide whether the explanation that best accounts for all of that is deception… or resurrection.

That is the rest of the story.

And it is still worth telling, carefully, patiently, and with confidence that the truth can bear the weight of honest history.

References

Primary Ancient Sources

Josephus, F. (1987). The Jewish War (G. A. Williamson, Trans.; rev. ed.). Penguin Classics. (Original work ca. AD 75)

Josephus, F. (1987). The Antiquities of the Jews (L. H. Feldman, Trans.). Harvard University Press. (Original work ca. AD 93)

Justin Martyr. (2003). Dialogue with Trypho (T. B. Falls, Trans.). Catholic University of America Press. (Original work ca. AD 155)

Origen. (1954). Against Celsus (H. Chadwick, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work ca. AD 248)

Tertullian. (1959). Apology and De Spectaculis (T. R. Glover, Trans.). Harvard University Press. (Original works ca. AD 197–200)

The Babylonian Talmud. (2005). Sanhedrin (I. Epstein, Ed.). Soncino Press. (Compiled ca. AD 500; cited with historical caution)

New Testament Texts

The Holy Bible, Legacy Standard Bible. (2021). The Lockman Foundation.

(Primary citations: Matthew 27:62–66; 28:11–15; Acts; 1 Corinthians 15:3–8)

Archaeology and the Nazareth Inscription

Bruce, F. F. (1980). Jesus and Christian origins outside the New Testament. Eerdmans.

McRay, J. (1991). Archaeology and the New Testament. Baker Academic.

Habermas, G. R., & Licona, M. R. (2004). The case for the resurrection of Jesus. Kregel.

Cook, J. G. (2011). Roman attitudes toward Christians: From Claudius to Hadrian. Mohr Siebeck.

Roman Law, Burial Practices, and Historical Context

Sherwin-White, A. N. (1963). Roman society and Roman law in the New Testament. Oxford University Press.

Mason, S. (2003). Josephus and the New Testament (2nd ed.). Hendrickson.

Feldman, L. H. (1998). Josephus’ interpretation of the Bible. University of California Press.

Evans, C. A. (2008). Jesus and His world: The archaeological evidence. Westminster John Knox Press.

Stanton, G. (2001). The Gospels and Jesus (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Resurrection Studies and Historical Synthesis

Wright, N. T. (2003). The resurrection of the Son of God. Fortress Press.

Meier, J. P. (1991). A marginal Jew: Rethinking the historical Jesus (Vol. 1). Yale University Press.

Marble Provenance and Archaeometry

Harrell, J. A. (2012). Classical marble: Geochemistry, technology, trade. Oxford University Press.

Lazzarini, L. (2004). Marble provenance studies: A review. Archaeometry, 46(4), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00191.x

Ancient sources are cited in standard English translations. Rabbinic material is referenced cautiously as later tradition reflecting polemical memory rather than direct first-century testimony.