What Archaeology Can — and Cannot — Tell Us About Babel

I saw it on Facebook.

Which, as a general rule, is a sentence that should make historians, pastors, and anyone who has ever wrestled with footnotes pause, take a breath, and maybe refill their coffee.

The post was confident. Bold. Sharply worded. It claimed that archaeologists have finally uncovered evidence that confirms the biblical account of the Tower of Babel. The pieces seemed to fit neatly. A massive ziggurat in Babylon. A unified law code. Ancient tablets speaking of multiple languages. A tidy conclusion followed close behind: history has caught up with the Bible at last.

It is an understandable impulse. Christians want Scripture vindicated. We want the stones to cry out. And sometimes, they do.

But history is not served by speed, and theology is not strengthened by overstatement. If we want to honor both Scripture and the past honestly, we need to slow down, define our terms, and let each discipline do the work it was meant to do.

So let’s walk carefully through the evidence. Not to diminish the Bible, but to understand it better. And then, like any good investigation, we will tell the rest of the story.

The World Genesis Assumes

Before we ever talk about towers, we need to remember something basic but often forgotten. Genesis is not written to modern readers. It was given to people who already lived in a world of cities, kings, temples, and empire-building ambition.

Genesis 1–11 moves quickly. Creation. Fall. Flood. Nations. It is not trying to be exhaustive. It is establishing a worldview. It explains how the world became the way it is and, more importantly, why humanity so consistently misuses what God gives.

By the time we reach Genesis 11, the text assumes settled populations, shared technology, and collective purpose. Humanity migrates east, finds a plain, and begins to build. Brick replaces stone. Mortar replaces mud. This is not primitive society. It is organized civilization.

That detail matters. Genesis is not narrating myth in the abstract. It is addressing the same kind of world archaeology later uncovers.

A Tower That Touched the Heavens

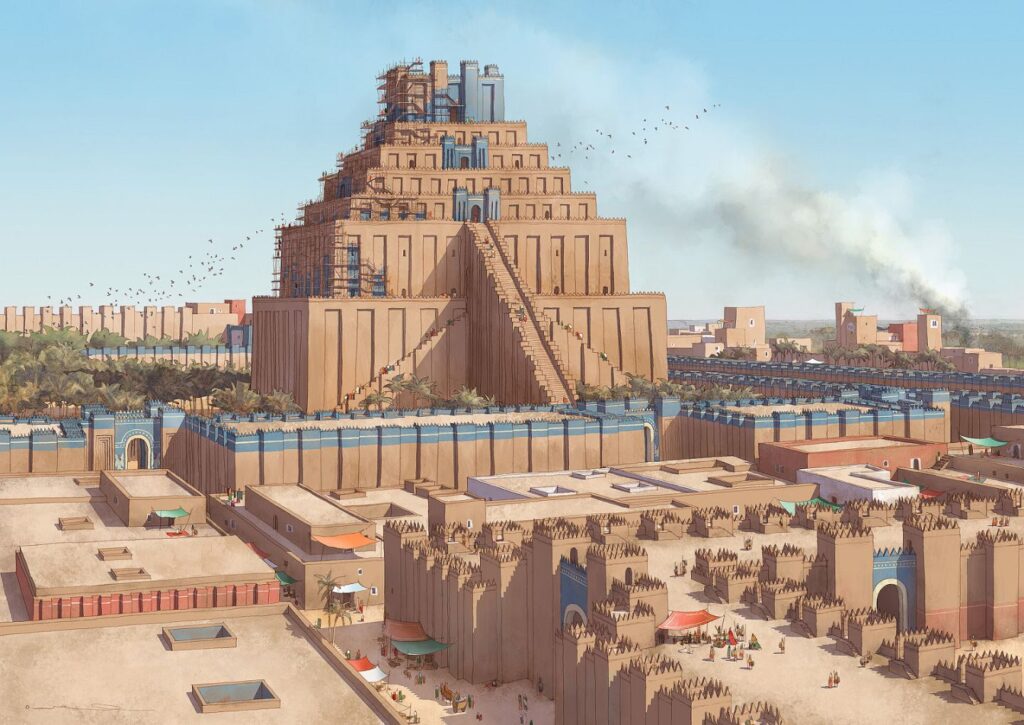

Excavations at Babylon have long identified the remains of a monumental stepped temple known as Etemenanki. Ancient texts call it “The House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth.” That is not poetic excess. It is a theological claim.

Ziggurats were not designed as places for congregational worship. They were cosmic symbols. Artificial mountains meant to bridge heaven and earth. Their stairways ascended upward toward a shrine where a god might descend. The message was unmistakable: this city stands at the center of the cosmos.

Babylonian kings boasted openly about this. Nebuchadnezzar II left inscriptions claiming he rebuilt Etemenanki so that its summit would rival the heavens. This is royal ideology, not metaphor.

Now pause and read Genesis 11:4 again: “Come, let us build for ourselves a city, and a tower whose top is in heaven.”

Suddenly the language sharpens. Genesis is not inventing an odd phrase. It is engaging a known concept. Archaeology helps us see what the builders thought they were doing.

What archaeology does not do is identify Etemenanki as the Tower of Babel. The structure as we know it belongs primarily to the second and first millennia BC, well after the period Genesis situates Babel. What Etemenanki represents is continuity of ambition, not a photographic match.

And that distinction is crucial.

What Genesis Is Actually Critiquing

The Bible is not impressed by scale. Scripture rarely pauses to marvel at human achievement unless it is framed by obedience. The tower at Babel is not condemned because it is tall, but because of what it represents.

The builders say, “Let us make a name for ourselves.” That phrase should ring alarm bells. Throughout Scripture, God promises to make His name great. Here, humanity takes that role for itself.

This is not about curiosity or engineering. It is about autonomy. Babel is the attempt to secure identity, unity, and permanence without reference to God. The tower is the symbol. The city is the system. The name is the goal.

Archaeology helps us understand the symbol. Scripture gives us the diagnosis.

Empire, Kingship, and the Illusion of Order

The Facebook post also appeals to the famous Code of Hammurabi as evidence of early empire, tying it to Nimrod’s kingdom in Genesis 10.

The Code of Hammurabi is indeed one of the most important artifacts from the ancient world. Carved in stone and publicly displayed, it represents centralized authority, legal uniformity, and divine sanction for kingship.

The stele’s relief shows Hammurabi receiving authority from Shamash, the god of justice. The message is clear: the king rules by divine appointment. The laws below regulate everything from theft to marriage to bodily injury.

This tells us something vital about the world Genesis describes. Empires did emerge. Kings did consolidate power. Law was used to unify diverse peoples under a single system.

But Hammurabi ruled around 1750 BC, centuries after the events Genesis 10–11 describes. His code does not confirm Nimrod, nor does it prove Babel. It does something else. It shows us where the trajectory of human ambition leads.

Genesis 10 presents the spread of nations. Genesis 11 interrupts that spread with a forced unity that resists God’s command to fill the earth. Genesis 12 then introduces Abraham, through whom God will bless all nations.

Empire is not redemption. It is a counterfeit unity enforced by power. The Code of Hammurabi shows how effective that counterfeit can look.

Babel and the Meaning of “Confusion”

Genesis 11:9 tells us the city was called Babel because the Lord “confused” the language of the people. In Hebrew, this is a deliberate wordplay on balal, meaning “to mix” or “to confuse.”

Historically, the name Babylon comes from the Akkadian Bab-ilu, “gate of the god(s).” That difference is not a problem. It is the point.

Scripture is not making a linguistic claim. It is making a theological judgment. What humans called the gateway to heaven, God names the place of confusion.

This is one of Scripture’s most effective rhetorical moves. It takes the empire’s proud self-description and turns it upside down. Babylon thought it was the axis of heaven and earth. God reveals it as the birthplace of fragmentation.

That pattern will repeat throughout Scripture.

Ancient Texts and Shared Memory

The post also appeals to ancient Mesopotamian literature, especially the Sumerian story Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. This text reflects concern about language diversity and divine involvement in human speech.

This matters. It tells us that ancient people noticed linguistic fragmentation and tried to explain it. They preserved memories of unity lost and communication strained.

But the theological frame is entirely different.

In Mesopotamian texts, language diversity is an inconvenience or a cosmic adjustment. It is not moral judgment. It is not restraint. It is not mercy.

Genesis reframes the same human reality through the character of God. Language division is not punishment for curiosity. It is restraint against self-destruction. It slows humanity down. It forces dispersion. It keeps any one culture from becoming godlike in power.

Archaeology gives us the question. Scripture gives us the answer.

What Archaeology Can and Cannot Do

Here is where we must be precise.

Archaeology does not prove the Tower of Babel the way it proves a city wall or a law code. It cannot reconstruct the moment God confused languages. It cannot identify a single ruin and say, “This is the tower.”

What archaeology does do is confirm the world Genesis presupposes. It shows us cities capable of massive projects. It shows us towers built to reach heaven. It shows us kings claiming divine authority. It shows us unified systems that promise order and meaning.

In other words, archaeology confirms that Genesis knows what it is talking about.

Scripture does not stand on trial before archaeology. Archaeology simply reminds us how well Scripture understands the human condition.

Babel in the Larger Biblical Story

Genesis 11 is not the end of the story. It is the setup.

Immediately after Babel, God calls Abram. Where Babel sought unity through human effort, God promises blessing through divine initiative. Where Babel tried to make a name, God promises to make Abram’s name great. Where Babel gathered people into a city, God sends Abram out in faith.

This is not accidental. Babel is the backdrop against which redemption begins.

And the story does not stop there.

At Pentecost in Acts 2, the division of languages is not erased, but redeemed. People hear the gospel in their own tongues. Unity does not come through sameness, but through shared allegiance to Christ.

In Revelation 7, a multitude from every nation, tribe, people, and language stands before the throne. Babel is not undone. It is fulfilled.

The Rest of the Story

So how should we tell this story?

Not by saying archaeology has “caught up” with the Bible. That framing puts Scripture in the dock and turns history into a courtroom witness. That is not how truth works.

We tell the story by saying this: archaeology shows us why Babel mattered. It shows us the kind of world Genesis was addressing and the ambitions it confronted. Scripture then interprets that world with divine clarity.

Babylon built towers and called them holy.

Genesis called them proud.

Babylon sought unity through empire.

Genesis warned that such unity would fracture.

Babylon named itself the gate of heaven.

God named it the birthplace of confusion.

That is not coincidence. That is revelation speaking into history.

Walk It Out

Babel is not ancient trivia. It is a mirror.

We still build towers. We still chase unity on our own terms. We still believe scale, technology, or policy can save us. We still try to make names for ourselves.

Genesis reminds us that God is not impressed by height. He is concerned with faithfulness. True unity does not come from bricks or systems, but from obedience and grace.

Archaeology does not weaken that message. It sharpens it.

And when we tell the story carefully, slowly, and truthfully, we honor both the Word of God and the world it addresses.

That is the rest of the story.

References

Alexander, R. J. (2008). From paradise to the promised land: An introduction to the Pentateuch (3rd ed.). Baker Academic.

Hallo, W. W., & Younger, K. L. (Eds.). (2003). The context of Scripture (Vols. 1–3). Brill.

Heidel, A. (1963). The Babylonian Genesis: The story of creation (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Hess, R. S. (1994). Studies in the personal names of Genesis 1–11. Eisenbrauns.

Hiebert, T. (1999). The Yahwist’s landscape: Nature and religion in early Israel. Oxford University Press.

Horsnell, M. (1999). The year-name system and the date of the first dynasty of Babylon. University of London Press.

Kramer, S. N. (1961). Sumerian mythology: A study of spiritual and literary achievement in the third millennium B.C. Harper & Brothers.

Lambert, W. G. (2013). Babylonian creation myths. Eisenbrauns.

Leick, G. (2003). Mesopotamia: The invention of the city. Penguin.

Matthews, V. H., Chavalas, M. W., & Walton, J. H. (2000). The IVP Bible background commentary: Old Testament. InterVarsity Press.

Nebuchadnezzar II. (6th century BC). Building inscriptions (translated excerpts in Hallo & Younger, 2003).

Roth, M. T. (1997). Law collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (2nd ed.). Scholars Press.

Sarna, N. M. (1989). Genesis: The traditional Hebrew text with the new JPS translation. Jewish Publication Society.

Steinkeller, P. (1999). On rulers, priests and sacred marriage: Tracing the evolution of early Sumerian kingship. In K. Watanabe (Ed.), Priests and officials in the ancient Near East (pp. 103–137). Winter.

Van de Mieroop, M. (2016). A history of the ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Walton, J. H. (2001). Ancient Near Eastern thought and the Old Testament. Baker Academic.

Walton, J. H. (2015). The lost world of Adam and Eve. IVP Academic.

Westermann, C. (1984). Genesis 1–11: A continental commentary. Fortress Press.

Younger, K. L. (1990). Ancient conquest accounts: A study in ancient Near Eastern and biblical history writing. JSOT Press.