What Scripture, Shared Memory, and the Evidence Actually Tell Us About the Flood

I saw this on Facebook.

Which, as a general rule, is a sentence that should cause historians, pastors, and anyone who has ever footnoted a claim to pause, take a breath, and maybe refill their coffee.

The post was confident. Bold. Sharply worded. It claimed that archaeology has uncovered something no global myth should ever show: the same flood story preserved everywhere. Clay tablets from Mesopotamia describing a catastrophic flood. A man warned to build a massive boat. Animals preserved. Birds released to find dry land. Then the big conclusion. Over two hundred flood stories from cultures across the world. Collapsing civilizations. Archaeology, finally, confirming the Bible.

It is easy to see why a post like that spreads. It feels like long overdue vindication. For believers who have grown tired of hearing Scripture dismissed as legend or myth, there is a quiet satisfaction in seeing science and history lined up on the same side. It feels like the ground itself is speaking up.

And to be fair, parts of the claim are true. There really are ancient flood tablets from Mesopotamia. They really do describe a catastrophic flood, a chosen survivor, a constructed vessel, and the preservation of life. Flood traditions really do appear in cultures scattered across the globe. Archaeology really does preserve memory.

But this is the moment where clarity matters more than enthusiasm.

Because when claims like this move too fast, they often end up flattening the very story they are trying to defend. Archaeology does not work the way Facebook posts suggest it does. History does not speak in slogans. And Scripture does not need exaggerated numbers or overstated conclusions to stand firm.

So before we declare victory or dismiss the claim outright, we need to slow down and ask better questions.

What does Genesis actually say about the flood?

What do the ancient tablets really describe?

Why does flood memory appear in so many cultures?

And what can archaeology legitimately tell us, and where does it reach its limits?

The goal here is not to debunk faith or to baptize every artifact we find. It is to tell the story carefully. To let Scripture speak first. To let evidence say what it can say, no more and no less. And to see whether the world archaeology uncovers actually looks like the world Genesis describes.

Because the most compelling case for the Bible has never been loud certainty. It has always been quiet coherence.

And that is where the rest of the story begins.

What Genesis Actually Claims

Before we bring archaeology into the room, we need to be clear about what Scripture itself is saying. Not what we assume it says. Not what we wish it said in an argument. What it actually claims.

Genesis 6–9 presents the Flood as a real, catastrophic judgment that reshapes the world and resets humanity’s trajectory. The language is sober. The tone is moral. The reason is explicit. Human violence had filled the earth. Corruption was not localized. Wickedness was not contained. The problem was not one bad city or one failed civilization. It was humanity as a whole.

That matters.

Genesis does not describe the Flood as a seasonal disaster or an unfortunate act of nature. It is portrayed as a deliberate act of divine judgment paired with deliberate divine preservation. God announces judgment. God instructs Noah. God preserves life through the ark. And after the waters recede, God establishes a covenant that governs the future of the world.

This is not myth language. It is covenant language.

The scope of the Flood in Genesis is global, not because the text is trying to impress us with scale, but because the moral problem it addresses is global. The text does not linger on mechanics. We are not given engineering diagrams or hydrological explanations. Genesis is not interested in satisfying modern scientific curiosity. It is interested in telling us why the world had to be judged and why the world was allowed to continue.

And just as important as the Flood itself is what comes immediately after.

Genesis 10 and 11 are not footnotes. They are the interpretive key.

After the Flood, humanity does not remain scattered randomly. Genesis presents a structured account of nations, families, and peoples. The Table of Nations in Genesis 10 is Scripture’s way of telling us that the world we now inhabit, divided by language and culture, still shares a common ancestry. This is theology doing anthropology before anthropology had a name.

Then comes Babel.

Genesis 11 explains why humanity, though united by origin and memory, becomes divided by language and culture. The confusion of tongues is not about God being threatened by architecture. It is about God restraining unified rebellion. The result is dispersion, not amnesia. Humanity spreads across the earth carrying shared history, shared trauma, and shared memory.

That sequence matters for everything that follows.

If the Flood occurred before Babel, then every people group carries some memory of it. If Babel fractured language and culture, then those memories would naturally diverge. Details would fade. Meanings would shift. Stories would localize. The core catastrophe would remain.

Genesis anticipates exactly that kind of world.

So when we later encounter flood traditions scattered across cultures, Genesis has already given us a framework to understand why similarity and difference coexist. Shared origin explains the overlap. Cultural dispersion explains the distortion.

This is why archaeology does not stand over Scripture as a judge. Scripture stands as the interpretive lens through which archaeology makes sense.

Before we ask whether ancient tablets or global traditions “confirm” the Bible, we need to see that the Bible already expects the kind of evidence we find. Genesis does not require perfect preservation of memory. It predicts fragmentation.

Which means the real question is not whether the world remembers a flood. It is whether the pattern of memory we see looks like the aftermath of judgment followed by dispersion.

That is where archaeology finally enters the conversation.

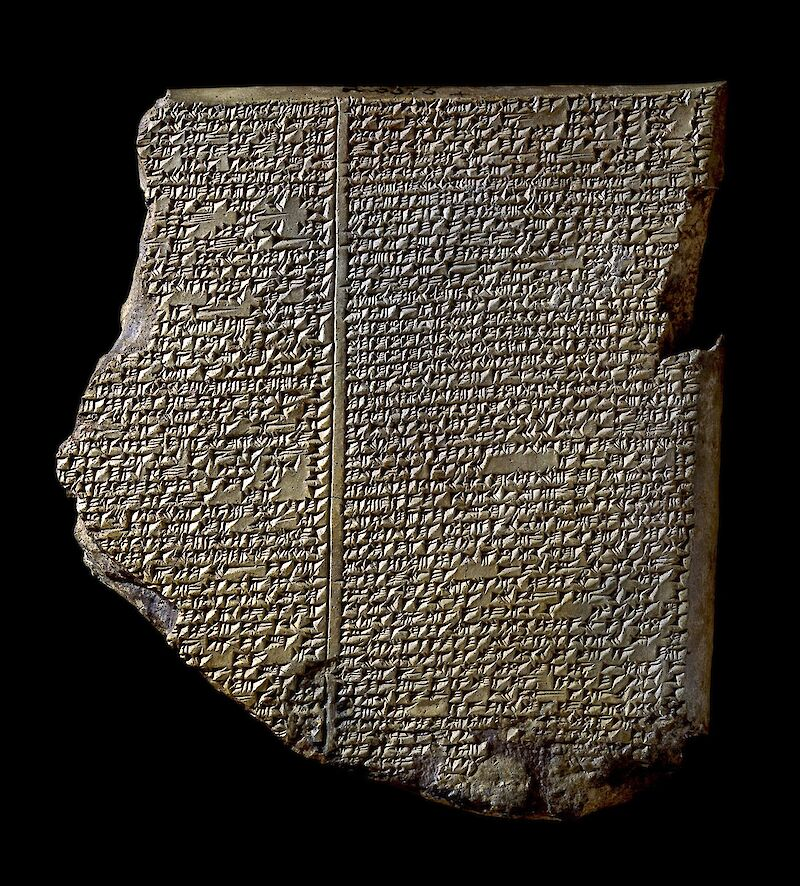

The Tablets That Refuse to Go Away

When people talk about archaeology and the flood, this is usually where the conversation begins. And for good reason.

Long before Genesis was copied onto scrolls or bound into a Bible, stories about a catastrophic flood were already being told in the ancient Near East. Not whispered. Not hinted at. Written down. Preserved in clay.

Among the most well-known are the flood accounts embedded in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Atrahasis Epic. These tablets come from Mesopotamia and are commonly dated to the early second millennium BCE, with roots in even older oral traditions. They describe a world-ending flood sent by the gods, a man warned in advance, the construction of a massive boat, the preservation of animals, the release of birds to find dry land, and a sacrifice offered after the waters recede.

Those parallels are not accidental, and they are not superficial.

Anyone who has actually read these texts knows they track the structure of Genesis 6–9 in ways that are difficult to ignore. This is not a vague “there was a flood once” similarity. It is a shared narrative framework. Warning. Vessel. Survival. Renewal.

And this is where many popular treatments go wrong.

Some rush to say Genesis copied these stories. Others rush to say these stories prove Genesis. Both miss the point.

The real question is not who borrowed from whom. The real question is why these stories exist at all, and why they are so similar at the level of structure while so different at the level of meaning.

Because the differences matter just as much as the parallels.

In the Mesopotamian accounts, the gods are divided, irritated, and inconsistent. Humanity is destroyed because it is noisy or inconvenient. One god warns the hero in secret. Another regrets the destruction after the fact. The flood happens, but it has no moral center. It is a disaster, not a judgment. Survival feels accidental. Mercy feels unstable.

Genesis tells a different story using familiar scaffolding.

In Genesis, there is no divine argument. There is no secret betrayal among gods. There is one righteous God who judges human violence and preserves life intentionally. Noah is not spared because he is clever or lucky, but because he is righteous. The flood is not an inconvenience. It is a response to moral corruption. And when the waters recede, God does not regret being caught off guard. He establishes a covenant.

Same memory. Different theology.

This is why the presence of these tablets does not weaken the biblical account. It sharpens it.

If Genesis were inventing a story from scratch, it would not land so comfortably in the ancient world’s memory. And if it were merely copying mythology, it would not stand apart so clearly in moral clarity and theological coherence.

What we are seeing in these tablets is not competition. It is preservation and distortion. A shared catastrophe remembered through different theological lenses.

And that is exactly what Genesis 10 and 11 prepare us to expect.

The closer a culture remains to the geographic and historical center of dispersion, the more intact the memory tends to be. The farther that memory travels, the more it fragments. The flood remains. The meaning shifts.

So the tablets matter. They matter a great deal. But not because they “prove” the Bible.

They matter because they show that the flood was already part of humanity’s remembered past, long before Israel ever told its version of the story. And they show that Genesis is not late myth-making, but early meaning-keeping.

The tablets preserve the echo.

Genesis preserves the reason.

And once we understand that distinction, we are finally ready to talk about flood stories beyond Mesopotamia, and why the world remembers more than skeptics often expect.

Why the World Remembers a Flood

Once we step outside Mesopotamia, the conversation often accelerates too quickly. Lists get longer. Numbers get bigger. Claims get louder. And the story gets thinner.

It is true that flood traditions appear in cultures scattered across the world. Versions of a great inundation show up in parts of Asia, the Americas, Oceania, and Europe. Some are brief. Some are elaborate. Some preserve striking similarities. Others barely resemble Genesis at all.

That mix is precisely the point.

What these traditions do not show is a world independently inventing the same story hundreds of times. What they do show is a shared memory carried outward, stretched across geography and time, and refracted through culture, language, and theology.

This is where Genesis 10 and 11 stop being background material and start doing explanatory work.

If humanity disperses from a common origin after a catastrophic event, then every people group carries some memory of that event. But memory is not static. It compresses. It adapts. It sheds details that no longer feel essential. Moral clarity fades. Symbolism grows. Geography reshapes the story.

A global event does not stay global in storytelling. It becomes local.

Mountains replace horizons. Rivers replace oceans. Familiar animals replace unfamiliar ones. The catastrophe remains, but it is retold in ways that make sense to a new environment and a new culture.

This is not evidence against historicity. It is evidence of human memory doing what it always does.

The mistake many modern readers make is assuming that true history should be preserved with perfect consistency across cultures. That expectation belongs to the age of printing presses and digital storage, not to oral societies. In oral cultures, what survives is not precision but significance. The question is not whether every detail is retained, but whether the core experience remains recognizable.

And it does.

Across cultures, the recurring elements are striking: an overwhelming flood, divine involvement, human survival, and a reset of the world. What changes is the explanation. The farther the memory travels from its origin, the more the theology erodes. Judgment becomes accident. Mercy becomes luck. The covenant disappears.

Genesis stands out not because it is louder, but because it is clearer.

It preserves the flood as moral history, not mythic spectacle. It remembers not just that water came, but why it came. And it anchors that memory in covenant, not chaos.

So when we encounter flood traditions around the world, the question is not whether they all independently confirm the Bible. The question is whether their similarities and differences make sense within the biblical framework.

They do.

Babel explains why humanity shares memory without sharing language. Dispersion explains why stories localize. Time explains why details fade. Theology explains why meaning fractures.

What would be strange is a world with no flood memory at all.

Instead, we find a world that cannot quite forget, even when it no longer agrees on why the waters rose.

That is not coincidence.

It is the kind of fractured remembrance we would expect from a family that scattered, carrying a shared trauma into every corner of the earth.

A Collapse, a Climate Event, and a Category Mistake

At this point, many modern arguments pivot to what is often called the 4.2 kiloyear event. It sounds technical, authoritative, and decisive. And it is real. But it is also frequently asked to carry more explanatory weight than it can bear.

Roughly around 2200 BCE, a number of early civilizations experienced significant stress. Archaeologists see evidence of prolonged drought, reduced agricultural output, political fragmentation, and in some regions, the abandonment of urban centers. The Akkadian Empire weakens. Parts of the Old Kingdom in Egypt struggle. The Indus Valley shows signs of reorganization. Trade networks thin. Monument building slows.

This was not imaginary. Something changed.

But here is where clarity matters.

The 4.2 kiloyear event describes a climate-driven stress period, not a global catastrophe. It was not synchronous everywhere. It was not uniform in effect. And it was not defined by flooding, but largely by aridity. Drought, not inundation, is the dominant signal in the data.

Cities were not swept away. They were slowly vacated.

Walls were not breached. Granaries ran dry.

This matters because the event is often pressed into service as an explanation for flood memory, and that simply does not work. A drought-driven collapse cannot account for global traditions of overwhelming water. Nor does the timing align well with the biblical chronology of the Flood, which Genesis places well before the rise and fall of early Bronze Age states.

What the 4.2 kiloyear event does explain is something else entirely.

It shows how fragile early civilizations were. How dependent they were on stable climate patterns. How quickly centralized systems could fracture when environmental conditions shifted. It reminds us that the post-Flood world was not a steady climb toward progress, but a vulnerable experiment in human organization.

In other words, it explains why ancient societies struggled. It does not explain why humanity remembers a flood.

This is a category mistake that appears often in popular treatments. When an event is dramatic and well-documented, there is a temptation to let it explain everything. But not every disruption leaves the same kind of memory. Drought leaves famine stories. Invasion leaves war stories. Floods leave flood stories.

The widespread memory of overwhelming water belongs to a different category of experience.

So the 4.2 kiloyear event should not be dismissed. It belongs in the conversation. It just does not belong at the center of the flood discussion. Treating it as the source of flood memory confuses stress with catastrophe and correlation with cause.

Ironically, placing it in its proper place actually strengthens the biblical framework. It shows that long after the Flood, the world was still unstable. Climate shocks still mattered. Human systems still failed. Genesis never promises otherwise.

The Flood explains why humanity was reset.

Events like the 4.2 kiloyear disruption explain why civilization remained fragile.

They are related, but they are not the same story.

And once we stop asking climate collapse to explain flood memory, we can finally turn to what the earth itself records about water, burial, and scale.

What the Earth Remembers

At some point in every flood conversation, we end up looking down.

Stories and tablets preserve memory, but the ground beneath our feet preserves something else. Not narrative. Not theology. Evidence.

Geology does not tell stories. It records processes. Layers. Deposits. Erosion. Burial. And when we look at those patterns honestly, without demanding that they say more than they can, a few things become difficult to ignore.

Much of the earth’s surface is covered in sedimentary rock. By definition, sedimentary layers are formed by the movement and deposition of material, most often by water. These layers extend not just across regions, but across continents. They stack. They repeat. They preserve fossils, sometimes in remarkable condition.

What is striking is not merely that water was involved. It is the scale and energy implied by the deposits.

Marine fossils appear at high elevations. Vast fossil graveyards show organisms buried rapidly, often without signs of prolonged decay or scavenging. Some fossils cross multiple sedimentary layers, suggesting burial occurred faster than those layers could have formed under slow, steady conditions. Large erosion surfaces appear where enormous amounts of material seem to have been removed before new layers were laid down.

Geologists debate how to interpret these features. That debate is real and ongoing. But the data itself is not imaginary. The earth bears marks of massive water movement, rapid burial, and large-scale erosion.

What geology does not do is tell us why these things happened.

Science is descriptive. It observes what is there and proposes models to explain it. Different models can sometimes account for the same data. That is not a failure of science. It is how science works. But it does mean that the data itself does not carry meaning. Interpretation does.

Genesis does not compete with geology at this level. It addresses a different question.

Geology can tell us that water moved sediment on a massive scale.

Scripture tells us why the world was judged and preserved.

This is where many conversations derail. Some insist geology must explicitly name the Flood to be useful. Others insist geology must exclude it to remain credible. Both demands misunderstand the nature of the discipline.

The biblical account of the Flood predicts a world that would look disturbed. Reshaped. Scarred. It does not promise a neat signature neatly labeled for modern observers. Catastrophe leaves complexity, not simplicity.

So when we look at the geological record and see evidence consistent with large-scale, high-energy water processes, we are not required to shout “proof.” But we are also not required to pretend the fit is accidental.

The ground remembers that something immense happened.

It does not remember the reason.

That task belongs to Scripture.

And once we allow geology to say what it can say, without forcing it to say what it cannot, we are free to return to the deeper question. Not whether the Flood left scars, but why it matters that it did.

Why This Conversation Matters More Than We Think

At this point, it would be easy to step back, tally up the evidence, and declare a win. Tablets, traditions, geology. Case closed.

But that impulse is exactly what keeps producing fragile arguments and disappointed believers.

Because the deepest issue here is not whether the Bible can survive archaeology. It can. The issue is what we think faith needs in order to feel secure.

Overstated claims usually do not come from arrogance. They come from anxiety. From years of hearing Scripture dismissed as myth. From the quiet fear that if we cannot point to something concrete, something measurable, something viral, then faith might lose ground.

So when a Facebook post promises that archaeology has finally confirmed everything, it scratches a real itch.

The problem is that shortcuts always cost more than they save.

When claims are inflated, thoughtful readers notice. When numbers are exaggerated, credibility erodes. When complex evidence is flattened into slogans, Scripture ends up looking weaker, not stronger. Not because it cannot stand up to scrutiny, but because it was never meant to be propped up that way.

The Bible does not present itself as a collection of artifacts waiting to be verified. It presents itself as God’s interpretation of history. It tells us what events mean, not just that they happened.

That distinction matters for discipleship.

If faith depends on the next archaeological discovery, it will always feel provisional. But if faith rests on the coherence of Scripture’s account of the world, then archaeology becomes what it should be: a conversation partner, not a crutch.

What is striking, when we slow down, is how often archaeology keeps stumbling into Scripture’s world. Not proving it in a laboratory sense, but finding itself at home in the same landscape. A world where catastrophe happened. Where memory fractured. Where humanity scattered. Where meaning eroded faster than events.

That kind of fit does not need hype.

It needs patience.

The Flood narrative is not fragile. It does not need exaggerated numbers or sweeping claims to survive. It needs to be told carefully, in full, with all its theological weight intact.

And when it is, the result is not triumphalism. It is confidence. Quiet, grounded confidence. The kind that can say, “Here is what we know, here is what we don’t, and here is why Scripture still makes sense of the whole.”

That kind of faith does not panic when evidence is complex.

It listens.

Which brings us back, one last time, to where we started.

The Rest of the Story

So let’s return to the Facebook post.

It wasn’t wrong to notice the flood tablets.

It wasn’t wrong to point out global flood traditions.

It wasn’t wrong to sense that archaeology keeps brushing up against the biblical story.

What it missed was the patience the story deserves.

Archaeology does not shout. It preserves. It fragments. It leaves us pieces and asks us to interpret them carefully. When we demand that it deliver final verdicts, we ask it to be something it was never meant to be. When we let it speak within its limits, it becomes something far more interesting.

It becomes a witness.

The ancient tablets witness to a remembered catastrophe.

Global traditions witness to a shared human trauma.

Geology witnesses to a world shaped by immense forces.

None of them explain why the waters came. None of them tell us what the event meant. None of them preserve the moral center of the story.

That is where Scripture speaks.

Genesis does not compete with archaeology. It interprets the same world archaeology uncovers. It explains why memory exists but fractures. Why cultures remember water but lose meaning. Why humanity carries echoes of judgment without clarity about covenant.

The Flood, as Genesis presents it, is not a myth waiting to be debunked or a science experiment waiting to be confirmed. It is a theological account of why the world is both preserved and broken. Why judgment did not end the story. And why mercy did not erase consequences.

When we slow down and tell the story carefully, something important happens.

We no longer need exaggerated numbers to feel confident.

We no longer need archaeology to carry theological weight it cannot bear.

We no longer need to fear complexity.

Instead, we are free to say something simpler and truer.

The world remembers a flood because something enormous happened.

The stories differ because humanity scattered and memory fractured.

The ground bears scars because catastrophe reshaped the earth.

And Scripture stands, not because it was finally proven, but because it continues to make sense of all of it.

That is the rest of the story.

Not loud.

Not rushed.

Just steady.

And steady is enough.