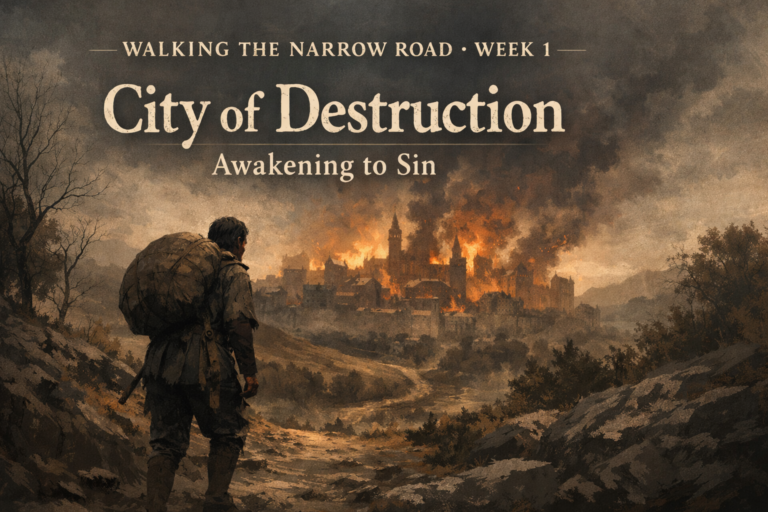

Why the Christian Life Has Always Been a Journey

This is part of the Walking the Narrow Road Road: A Year with The Pilgrim’s Progress

I’ve noticed something about the stories we return to again and again.

We are drawn to journeys.

From the quiet comfort of the Shire in The Hobbit, to the long and costly road that winds through Middle-earth in The Lord of the Rings, we understand almost instinctively that something important happens only after someone leaves home. The same pull shows up in the halls of Hogwarts in Harry Potter, and in the courage of ordinary kids facing extraordinary darkness in Stranger Things. Different worlds. Different dangers. The same pattern.

Someone steps out. Something is lost. Something is learned. No one comes back unchanged.

We don’t love these stories because they are easy. I think we love them because they tell the truth. Growth costs something. Courage isn’t discovered in comfort. Loyalty is tested under pressure. Evil is real, and it must be faced rather than ignored. The road shapes the traveler.

What’s striking to me is how natural this feels. No one has to teach us to recognize the power of a journey. We already know it. We sense that the most meaningful changes in life don’t happen all at once. They unfold slowly, through movement, resistance, choice, and endurance. Becoming who we are meant to be usually requires walking through things we would never choose on our own.

That instinct points to something deeper.

Our love for journey stories isn’t accidental. It reflects the way we experience life itself. We are always moving through seasons, decisions, losses, callings, and hopes. Even when we try to stand still, life keeps carrying us forward. We are shaped by the paths we take and the ones we refuse.

And yet, if I’m honest, this is where the tension shows up. We love journeys in stories, but we resist them in real life. We want transformation without process. Growth without discomfort. Faith without cost. We prefer arrival to obedience, answers to trust, clarity to courage.

Stories remind us that this isn’t how things actually work.

They train our hearts to accept a truth we might otherwise avoid. The road matters. The walking matters. Who we become along the way matters.

And that raises a question worth sitting with before we take another step.

If we love journeys so much in story, what does it mean that Scripture describes life with God the same way?

We Were Made for Pilgrimage

When Scripture speaks about life with God, it doesn’t reach first for the language of arrival. It reaches for the language of journey.

That matters.

From the opening pages of the Bible, God’s people are described as people on the move. Abraham is called to leave what is familiar without being given a detailed map. He is promised a land, but he spends his life living in tents. Hebrews tells us plainly that he was looking for a city whose architect and builder is God, a place he never fully reached in his lifetime.

That pattern repeats itself again and again. Israel is redeemed from slavery, but redemption does not drop them straight into rest. It leads them into wilderness. The Psalms give voice to travelers climbing toward worship, step by step, song by song. Even when God’s people are settled in the land, exile returns them to the posture of waiting, longing, and hoping for restoration.

By the time we reach the New Testament, the language hasn’t changed. Believers are called strangers and exiles. Jesus does not invite people merely to agree with Him. He calls them to follow Him. His invitations are directional. “Come after Me.” “Take up your cross.” “Walk while you have the light.”

What often goes unnoticed is how literally this played out in the early church.

Much of the New Testament was written by a man who spent his life on the road. Paul carried the gospel across the Roman world, traveling thousands of miles on the vast network of Roman roads. Those roads were engineered for empire, control, and military power. God repurposed them for redemption.

Paul’s letters were shaped by movement. Churches were planted along trade routes. Doctrine traveled by foot, by ship, and by suffering. The gospel advanced not through comfort, but through obedience that kept walking, even when the road led to prison, persecution, or exhaustion.

Christianity did not spread because believers stayed put and waited for clarity. It spread because they trusted God enough to move.

The Bible does not describe the Christian life as a moment to be preserved, but a road to be walked.

That challenges us, because we often want faith to be something we possess rather than something that carries us forward. We want assurance without obedience, comfort without trust, growth without the slow work of endurance. Scripture gently, and sometimes sharply, refuses that vision. Faith is alive. And living things move.

Even the narrowness of the road Jesus describes makes sense in this light. Narrow roads require attention. They demand commitment. You can’t drift on them. You have to walk deliberately, eyes up, steps measured, trusting that the path has been marked by Someone who knows the way.

What I find striking is that Scripture never treats this pilgrim identity as optional or advanced. It’s not reserved for spiritual elites. It’s the normal shape of life with God in a world that is not yet what it will be. To belong to Him is to be on the way somewhere.

This reframes how we understand both struggle and hope. Difficulty does not mean we have stepped off the road. Often it means we are on it. Waiting does not mean failure. It means we are between promise and fulfillment. Faithfulness is not measured by how quickly we arrive, but by whether we keep walking.

When Scripture calls us pilgrims, it is not diminishing the present. It is giving it meaning. Every step matters because it is part of a larger journey God Himself has set in motion.

And that leads us to something even more important.

The Christian journey is not first about our movement toward God. It is about God’s movement toward us.

The Greatest Journey of All

Before we talk any more about our walking, we need to lift our eyes.

Because the Christian journey does not begin with our movement toward God. It begins with God’s movement toward us.

That is the story the Bible is telling from beginning to end.

Scripture opens with God creating, ordering, and dwelling with His creation. When that fellowship is shattered by sin, the story does not turn into humanity’s long search for a hidden God. God goes looking. He calls. He covers. He promises. Even east of Eden, the journey of redemption has already begun.

From there, the pattern is consistent. God moves toward His people again and again. He comes to Abraham with a promise. He comes to Israel in power and mercy. He goes with them in cloud and fire. He sends prophets when they wander. He remains faithful even when His people are not.

And then, in the fullness of time, God does something that reshapes every road that follows.

He comes Himself.

The incarnation is not an idea. It is movement. God steps into human history, into time and flesh and weakness. Jesus does not shout salvation from a distance. He walks among us. He eats, teaches, heals, suffers, and obeys all the way to the cross. Redemption unfolds through steps taken in dust and blood, not abstractions spoken from heaven.

The cross itself stands at the center of the road. It is the place where God’s journey toward us reaches its deepest point. Judgment and mercy meet. Sin is dealt with. The way forward is opened.

And the story does not end there.

The resurrection is God’s declaration that the journey is going somewhere. New creation has begun, even if it is not yet complete. The risen Christ sends His followers back onto the road, not aimlessly, but with purpose. The church is born not as a settled institution, but as a people on mission, moving outward with the good news of what God has done.

This is why it matters that we frame our lives as pilgrimage.

Our walking is not an attempt to reach God on our own strength. It is a response to a God who has already come to us, who has already made a way, and who has already promised an end to the journey that is more solid and more glorious than anything we can see now.

When Scripture speaks of hope, it is not wishful thinking. It is confidence rooted in God’s completed work and future promise. We walk toward a destination God Himself has secured. We move forward because the road has already been opened.

This changes how we understand obedience. We are not earning arrival. We are living in light of it. We are not wandering in uncertainty. We are following a path marked by grace, even when it passes through hardship.

And it also explains why the Christian life feels unfinished.

We live between what Christ has accomplished and what He will one day complete. We walk in a world that still groans, even as we carry within us the hope of restoration. Pilgrimage is not a sign that something is wrong. It is the shape of faith in the space between promise and fulfillment.

Which brings us to the question at the heart of this series.

If God has written redemption as a journey, how are we meant to walk it faithfully?

That is where a pastor in prison, writing with Scripture in his bones, becomes a helpful guide.

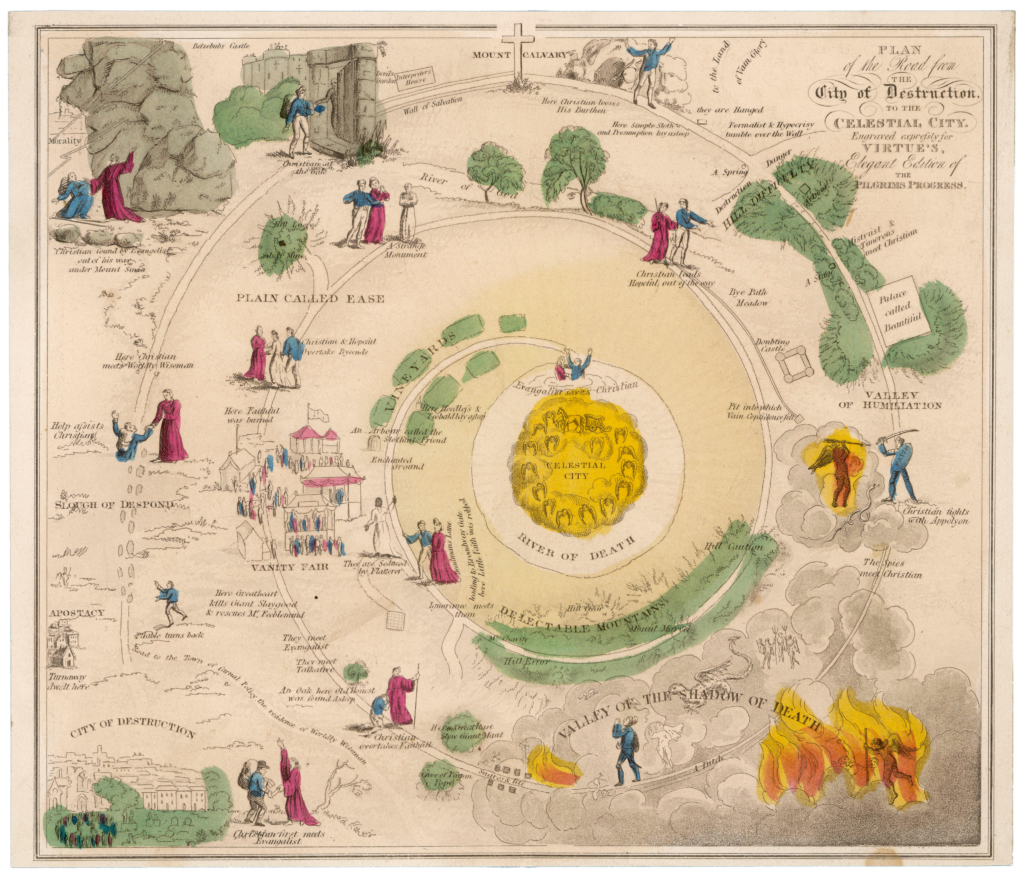

Why The Pilgrim’s Progress Exists

This is where John Bunyan steps onto the road with us.

The Pilgrim’s Progress did not come from a study lined with books and quiet hours. It came from a prison cell. Bunyan wrote as a pastor who had been silenced by the state for preaching without permission, separated from his family, and forced to reckon daily with what faithfulness truly costs. He could have gone free if he promised to stop preaching. He refused. Not out of stubbornness, but out of conscience bound to Scripture.

That matters, because Bunyan did not imagine the Christian life as a tidy progression of victories. He knew fear. He knew doubt. He knew the weight of a tender conscience and the exhaustion of long obedience under pressure. When he describes a man reading a book and collapsing under a burden, he is not being poetic. He is being honest.

Bunyan was not trying to invent theology through story. He was translating Scripture into a form that ordinary believers could carry with them. He wrote for people who did not have libraries, formal education, or social power. People who had to walk their faith out in public, under suspicion, sometimes under threat. His allegory gave them language for experiences they already knew but struggled to name.

That is why The Pilgrim’s Progress is so saturated with Scripture. Bunyan did not quote the Bible to decorate his story. He thought in biblical categories. His imagination was shaped by the Word, so when he told a story, Scripture came out naturally, the way blood flows from a wound. He expected the Bible to govern the journey, explain the dangers, and define the hope.

It is also why Bunyan chose allegory.

Allegory allows truth to be recognized before it is fully explained. It gives form to fear, conviction, temptation, despair, and perseverance. Instead of telling the reader what doubt feels like, Bunyan lets them sink into it. Instead of defining false teaching, he lets it speak. Instead of arguing for perseverance, he shows the cost of not enduring.

This was pastoral wisdom. Bunyan understood that believers are often formed more deeply by what they can see and feel than by what they can merely recite. Story trains discernment. It teaches us to recognize danger, truth, and grace when we encounter them in real life.

But it is important to be clear about what Bunyan is and is not doing.

He is not offering a replacement for Scripture. He is offering a companion under Scripture. The Bible tells us what is true. Bunyan helps us recognize what that truth looks like when it meets fear, pressure, confusion, and hope on the road.

That is why this book has endured. Not because it is clever, but because it is faithful. Not because it entertains, but because it tells the truth about the Christian life as it is actually lived.

Bunyan wrote for pilgrims who needed courage to keep walking.

And that is why, centuries later, his voice still helps us listen more carefully to Scripture and more honestly to our own hearts.

Why This Book Has Endured

One of the quiet tests of a book’s worth is not how widely it is praised, but when it is reached for.

The Pilgrim’s Progress has endured because people have turned to it in moments when optimism was thin and clarity was hard to find.

During the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln kept a copy of Bunyan’s work in his personal library. This was not a season for sentimental reading. The nation was divided. The cost of leadership was heavy. Death was constant. Lincoln did not turn to Bunyan for escape. He turned to him because the book told the truth about suffering, conscience, perseverance, and hope beyond the immediate horizon.

Bunyan’s pilgrims understood burden. They understood endurance. They understood walking forward without easy answers. That mattered to a leader carrying the weight of a fractured nation.

The same is true in the life of the church.

Charles H. Spurgeon, one of the greatest preachers of the nineteenth century, spoke often of his love for Bunyan. He urged his students to read The Pilgrim’s Progress until they were steeped in its language and soaked in Scripture. Spurgeon famously said that if you pricked Bunyan, he would bleed Bible. That was not exaggeration. It was recognition.

What Spurgeon admired was not Bunyan’s imagination alone, but his saturation in the Word of God. Bunyan did not merely know Scripture. Scripture had shaped how he saw the world. That is why his allegory never drifts into fantasy detached from reality. It remains tethered to truth, anchored in the gospel, and oriented toward hope.

This is why the book has lasted across centuries, cultures, and crises.

It has been read by prisoners and presidents, pastors and ordinary believers, people with formal education and people without it. It has survived not because it flatters the reader, but because it names the road honestly. It tells the truth about sin without despair, about suffering without sentimentality, and about hope without denial.

Books that endure do so because they help us live faithfully when life does not cooperate.

The Pilgrim’s Progress has done that for generations, not by offering shortcuts, but by reminding readers that the road God sets before His people, however narrow, always leads somewhere real.

And that brings us to you, the reader, standing at the beginning of this year-long walk.

Trail Guide: Before You Begin the Walk

Before you step onto this road, it helps to know the terrain.

This is not a straight path, and it is not a gentle one all the way through. Some stretches will feel clear and steady. Others will feel slow, uneven, or surprisingly heavy. There will be moments of relief and moments of resistance. That is normal for this road. It has always been so.

Early on, you should expect conviction before comfort. Scripture often awakens us before it reassures us. Some weeks may press on your conscience. Others may surface old fears, doubts, or weariness you thought you had already passed. These are not signs that something has gone wrong. They are signs that the journey is doing its work.

You should also expect that progress here is measured in faithfulness, not speed. We are not racing through scenes or collecting spiritual insights. We are walking slowly enough for Scripture to shape our instincts, our loves, and our endurance. Some weeks will feel demanding. Others will feel like rest. Both are part of the path God has marked.

As you walk, keep your posture simple.

Read slowly.

Pay attention.

Resist the urge to resolve everything immediately.

Pilgrimage is not about mastering the road. It is about learning to trust the One who laid it out.

You will notice along the way that Christian stumbles. He hesitates. He misunderstands. He sometimes chooses poorly. The story does not hide that. It also does not abandon him. This journey honors perseverance under grace, not flawless performance. That is the kind of faith Scripture commends, and the kind this road is meant to form.

You do not need to see the entire route to begin. God has never required that of His people. He has always met them one step at a time, providing light enough for the next stretch and strength enough for the day.

This first week is about orientation. About understanding the kind of journey Scripture says we are on and the kind of guide Bunyan will be along the way. Next week, the City of Destruction will come into view, and the weight of reality will be hard to ignore. That is not cruelty. It is mercy. Awakening always comes before rescue.

So before you start walking, take a breath.

Pack humility.

Carry patience.

Keep your eyes lifted toward the hope ahead.

The trailhead is here.

The road has been walked before.

And the God who marked it is faithful to meet His people along the way.

Selah.

Walk it out.