Introduction: The Illusion of Neutrality

Every few years, the debate reignites: should the Ten Commandments be displayed in public schools? Advocates see them as the foundation of morality and law; opponents cry “indoctrination” and “unconstitutional.” Courtrooms have ruled, legislatures have debated, and parents have argued, but beneath the surface, a deeper issue lurks.

The question isn’t whether schools should teach religion. The question is which religion they already teach.

What Is Religion?

Whenever the Ten Commandments and public education debate resurfaces, one question sits at the root of the issue: What do we mean by “religion”? If we define it too narrowly, as only church services, hymnbooks, and sacred creeds, we miss the deeper reality. Religion is bigger than ritual. It is about the ultimate reality.

- Biblically, religion is devotion and worship. It is the heart’s highest allegiance, either to the true God (Deut. 6:4–5) or to idols (Rom. 1:25). Everyone worships; the only difference is what or whom we worship.

- Philosophically, religion is a comprehensive worldview that answers life’s central questions: Where did we come from? Why are we here? How should we live? Where are we going? Whether the answer is “created by God” or “random chance,” it functions religiously because it frames ultimate meaning.

- Legally, the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized this broader definition. In Torcaso v. Watkins (1961), the Court listed secular humanism among “religions” for legal purposes because it provides answers to ultimate questions.

This matters because it explodes the myth of neutrality. When public schools say, “We can’t teach the Bible, that’s religious,” but then turn around and teach naturalism, humanism, or critical theory as unquestionable truth, they are not being neutral. They are establishing a different religion: the religion of secularism.

An Illustration

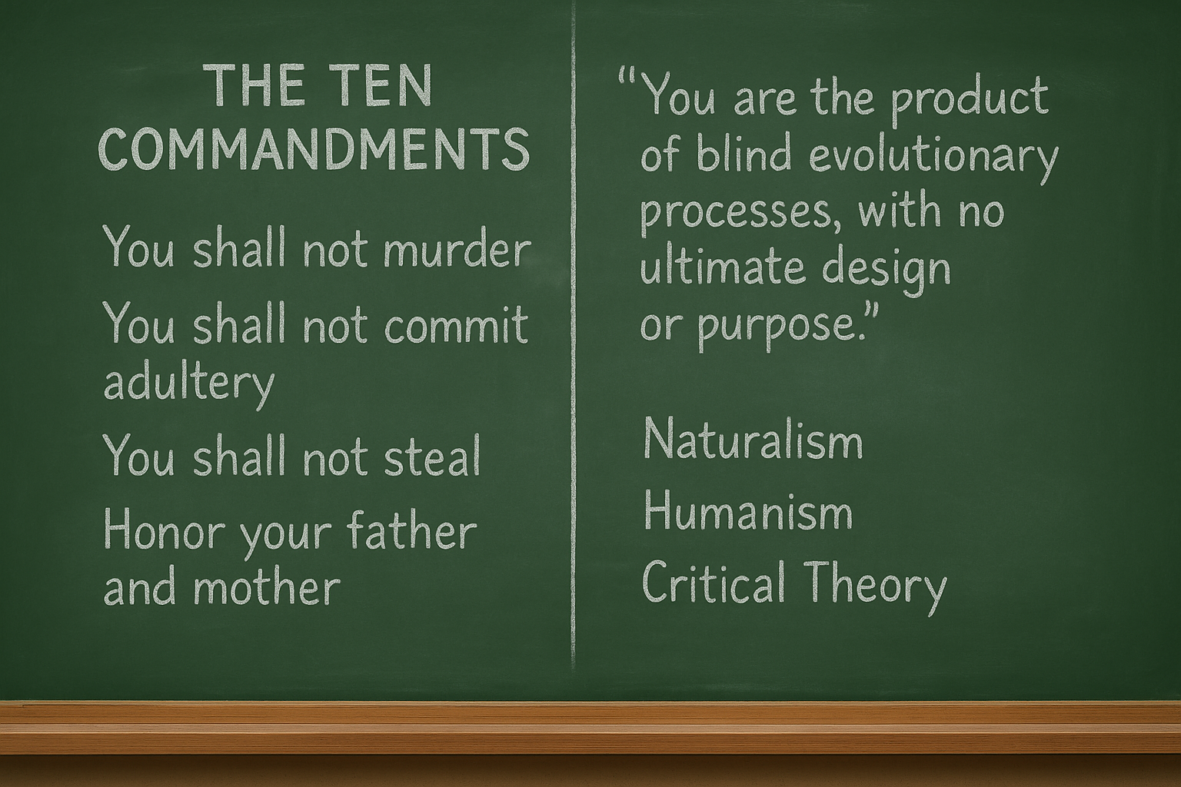

Imagine two classrooms.

- In one, a teacher posts the Ten Commandments on the wall: “You shall not murder… You shall not steal… Honor your father and mother.” The purpose is moral guidance, yet courts strike it down as unconstitutional religious indoctrination.

- In the other, a teacher lectures on human origins: “You are the product of blind evolutionary processes, with no ultimate design or purpose.” Students are told this is science, not worldview, even though it makes sweeping claims about origin, meaning, and destiny.

Both classrooms are teaching answers to the deepest questions of life. The first is labeled “religious,” the second “neutral.” But in reality, both are religious in nature, because both catechize students into a worldview. The only difference is which “god” is enthroned at the front of the classroom: the God who made us, or the god of secular autonomy.

As the theologian G.K. Chesterton once quipped, “When men choose not to believe in God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing. They then become capable of believing in anything.” Education is never a vacuum; it always orients students toward some view of reality, morality, and destiny. The only real question is: Which faith system is forming the next generation?

The Constitutional Debate

The next layer of the argument is constitutional. Advocates for removing the Ten Commandments from public schools often appeal to the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

But here is the crucial question: What did the framers mean by “establishment of religion”?

1. Original Meaning

The Establishment Clause was drafted in a context where the memory of state churches loomed large.

- In England, the Anglican Church was the official religion; taxes funded clergy; dissenters were fined or barred from office.

- The Founders wanted no such arrangement in America. The clause was meant to prevent Congress from creating a national church or coercing citizens into one sect.

It did not mean stripping religion from public life. In fact, many early states maintained their own religious influences well into the 19th century, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 (passed under the Confederation Congress and reaffirmed by the First Congress) declared:

“Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

2. The Shift in Interpretation

For much of American history, Bible reading and prayer were common in schools. The shift came in the mid-20th century when the Supreme Court applied the Establishment Clause to states through the 14th Amendment (Everson v. Board of Education, 1947). The Court began to speak of a “wall of separation between church and state”, a phrase borrowed from Jefferson’s private letter, not the Constitution itself.

By 1962–63, school-sponsored prayer and Bible reading were struck down (Engel v. Vitale; Abington v. Schempp). In Stone v. Graham (1980), the Court ruled that even posting the Ten Commandments in classrooms had “no secular purpose” and was therefore unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, in Van Orden v. Perry (2005), the Court allowed a Ten Commandments monument at the Texas State Capitol, because it was part of a larger historical display. Context mattered: in civic spaces, religion could be heritage; in classrooms, it was deemed indoctrination.

3. The Inconsistency

Here lies the tension. A monument in front of the courthouse is constitutional if framed as history. But a plaque on a classroom wall is unconstitutional because children might take it seriously.

This logic reveals an assumption: that religion in civic heritage is tolerable, but religion in moral formation is dangerous. Yet that was the very opposite of the Founders’ vision. Washington, Adams, and others insisted that religion and morality were essential to form citizens capable of liberty.

4. Worldview Clash

So, the constitutional debate is not only about law, it is about worldview. Courts are not being neutral when they exclude the Bible from education. They are privileging one worldview (secularism) over another (Judeo-Christian heritage). In the name of “non-establishment,” they have effectively established secularism as the state faith of the classroom.

Education, Indoctrination, or Critical Thinking?

The classroom is where lofty constitutional theory becomes lived reality. And here we face a crucial distinction: Is education about indoctrination or critical thinking?

1. Indoctrination Defined

Indoctrination is not simply “teaching.” Indoctrination is teaching in such a way that shuts down questions, discourages comparison, and presents one system as the only acceptable truth. It trains conformity, not discernment.

2. Critical Thinking Defined

Critical thinking, by contrast, exposes students to ideas, teaches them to weigh evidence, compare worldviews, and evaluate truth claims. It equips them to discern, rather than dictate what they must believe. True education must foster this kind of intellectual maturity.

3. The Classroom Double Standard

- When teachers present naturalistic evolution as fact, “You are here because of unguided processes, with no higher purpose”, that is treated as scientific neutrality. Students are not encouraged to test or compare it against other frameworks; they are expected to accept it.

- When schools present critical theory as the lens through which all history and society must be interpreted, students are not told, “This is one possible view.” They are taught, “This is the truth of oppression and liberation.”

That is indoctrination.

Yet if a teacher were to say, “The Ten Commandments shaped Western law, and Christianity offers one account of origin, morality, and destiny,” suddenly the system panics: “That’s indoctrination!”

4. The Real Issue

The inconsistency reveals the deeper problem: public schools have not escaped religion. They have simply replaced biblical categories with secular ones and labeled them “neutral.” But neutrality is a myth. Every classroom disciples hearts and minds toward some ultimate loyalty.

5. Biblical and Historical Reflection

- Biblically, Proverbs 1:7 declares that “the fear of Yahweh is the beginning of knowledge.” Excluding Him doesn’t make a classroom neutral; it makes it skewed.

- Historically, early American education was explicitly moral and religious. The purpose was to form citizens capable of virtue. By today’s standards, nearly every colonial school would be guilty of “indoctrination”, yet the fruit of that education gave us a generation capable of building the world’s most enduring republic.

👉 The choice before us is not whether we will indoctrinate, but which worldview will be taught uncritically, and which will be silenced in the name of neutrality.

Worldview vs. Worldview

At bottom, education is never value-free. It always transmits a worldview, a way of seeing reality and living within it. To claim that one system is “religion” while another is “neutral” simply disguises the fact that both are answering the same ultimate questions.

1. The Four Questions Every Worldview Must Answer

Philosophers often note that all belief systems, religious or secular, answer at least four basic questions:

- Origin: Where did we come from?

- Meaning: Why are we here?

- Morality: How should we live?

- Destiny: Where are we going?

2. Comparing the Claims

| Question | Biblical Worldview | Secular Humanism / Naturalism |

| Origin | Created by God, in His image (Gen. 1:1, 27). | Result of unguided natural processes, matter plus time plus chance. |

| Meaning | Life has purpose: to glorify God and enjoy Him forever (Isa. 43:7; 1 Cor. 10:31). | No ultimate meaning, purpose is self-defined, or survival of the fittest. |

| Morality | God’s Word defines right and wrong (Exod. 20; Matt. 22:37–40). | Morality is human-made, relative to culture or individual preference. |

| Destiny | Eternal accountability before God: judgment or salvation (Heb. 9:27; John 3:16). | No ultimate destiny beyond death; extinction or nothingness. |

3. The Classroom Reality

When schools ban the Ten Commandments but teach secular frameworks, they are not removing religion; they are replacing one religion with another. Both systems shape identity, morality, and destiny. Both require faith in an ultimate claim: either faith in the Creator God, or faith in a self-contained, godless universe.

4. Logical Implication

This means the debate over the Ten Commandments is not about whether schools should teach religion, but which religion they will teach. Will it be the Judeo-Christian heritage that shaped law, liberty, and civic virtue? Or the modern secular creed that insists man is the measure of all things?

👉 By setting these worldviews side by side, the double standard becomes clear: Secularism has been enthroned as the state religion of the classroom, even while claiming neutrality.

Bringing It All Together

The debate over the Ten Commandments in schools is often framed as a question of law: Does the Establishment Clause forbid it? But when we step back, it is more than legal, it is historical, philosophical, and deeply spiritual.

1. Biblically

Scripture teaches that all education is discipleship.

- Parents are charged with passing on truth (Deut. 6:6–7).

- The fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge (Prov. 1:7).

- Neutrality is a myth: to exclude God is already to enthrone another god.

2. Historically

The Founders did not envision a secular public square. They rejected a state church, but they affirmed the indispensability of religion and morality for liberty. Washington called them “indispensable supports.” Adams said the Constitution was written “only for a moral and religious people.” The Northwest Ordinance explicitly tied schools to “religion, morality, and knowledge.”

The 20th-century shift to strict secularism was not a continuity with the founding vision; it was a departure.

3. Constitutionally

The Establishment Clause was meant to prevent coercion by a national church, not to expunge biblical morality from education. The current interpretation has created a double standard: religious frameworks are censored, secular frameworks are enthroned, and this is mislabeled “neutrality.”

4. Logically

All education teaches a worldview.

- To teach evolution as an unquestionable fact is to answer the question of origin.

- To teach morality as culturally relative is to answer the question of ethics.

- To teach history through Marxist or critical theory categories is to answer the question of meaning.

Secularism is not the absence of religion; it is its own religion, offering its own catechism.

5. The Real Question

Thus, the real debate is not whether schools will teach religion, but which religion they will teach. Will it be the biblical worldview that shaped Western liberty, or the secular worldview that denies transcendence? Will it be a heritage that grounds virtue in God’s law, or an ideology that makes man the measure of all things?

Conclusion: A Call to Honesty

The fight over the Ten Commandments in classrooms is not merely about wall plaques; it is about worldview honesty. To exclude the Judeo-Christian worldview while enthroning secularism is not neutrality; it is establishment.

As Christians, we must remember that the ultimate responsibility for discipleship does not belong to the state but to the home and the church. Yet as citizens, we can and must insist on intellectual honesty: if schools claim to teach critical thinking, they must expose students to the biblical worldview alongside others, not silence it.

The Founders knew that liberty could not survive without religion and morality. The Bible declares that wisdom begins with the fear of the Lord. And logic itself demands that all worldviews be examined on equal terms.

👉 Until we face that truth, we will continue to call indoctrination “neutrality” and call neutrality “indoctrination.” The question remains before us, plain and urgent: Which faith will form the next generation?