This is part of an unexpected series:

- Part 1: The Spirit Tested: Texas A&M

- Part 2: Integrity Tested, Integrity Demanded

- Part 3: Cancel Culture Tested

- Part 4: Academic Freedom Tested

- Part 5: Leadership Tested

Introduction

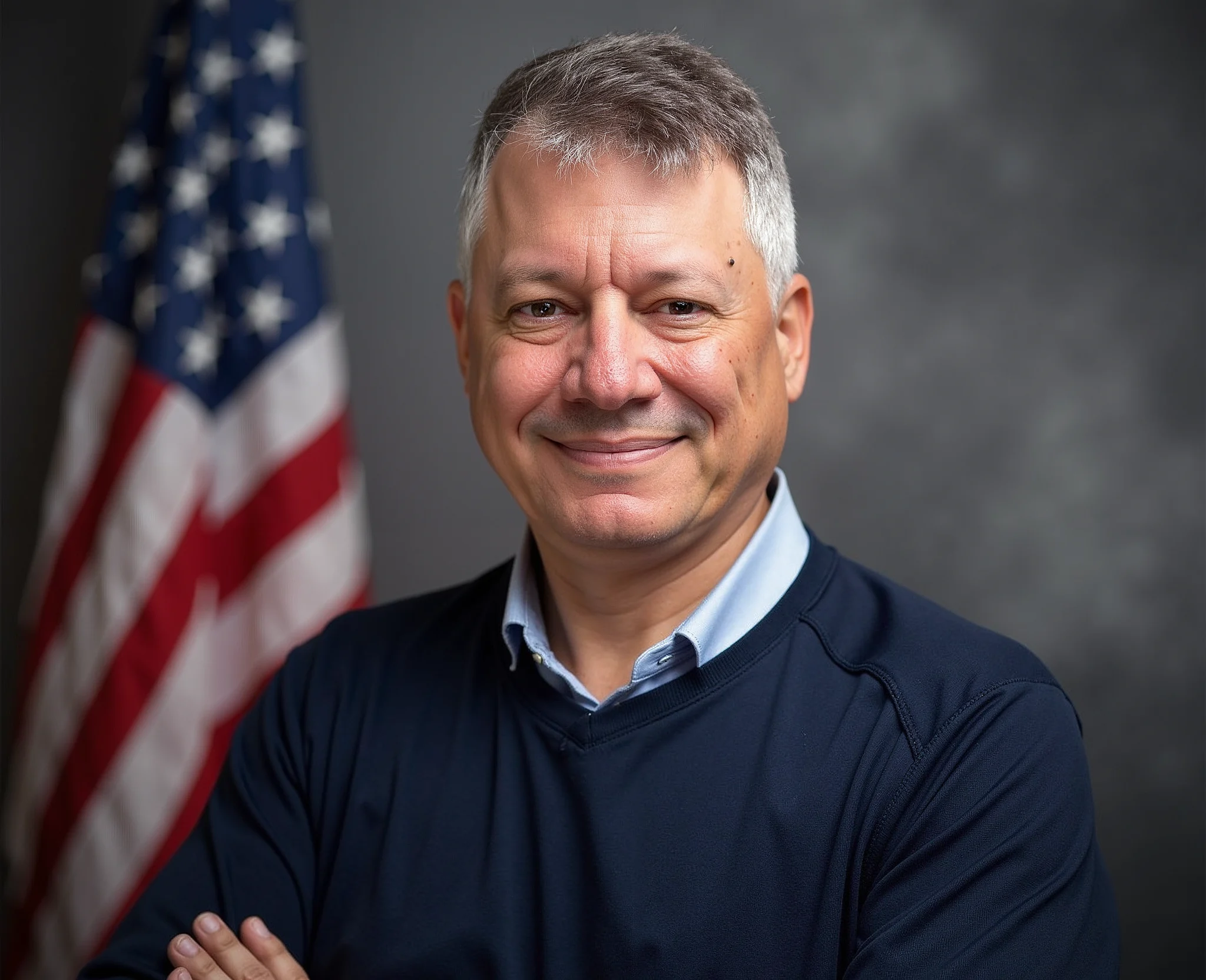

When General Mark Welsh III announced his resignation as president of Texas A&M University, the news sent ripples far beyond College Station. For Aggies, it marked the second time in as many years that their flagship university had lost a president in controversy. For Texans, it exposed once again the uneasy intersection of higher education, politics, and culture. And for Christians, it raised perennial questions about integrity, leadership, and the pressures of serving faithfully in a hostile age.

Welsh’s departure cannot be understood in isolation. It comes in the wake of the Kathy Banks controversy, the Kathleen McElroy hiring debacle, the ongoing national battles over diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), and the sharpening scrutiny of what is taught in America’s classrooms. His resignation capped months of escalating tension over a professor’s use of children’s literature to promote gender ideology, a conflict that quickly moved from one classroom in the summer semester to the office of the president, and eventually, to the halls of state politics.

To many, Welsh was the perfect Aggie president. A retired four-star general, former Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, and beloved dean of the Bush School of Government and Public Service, he embodied integrity, steady leadership, and a deep love for students. His calm voice and approachable presence earned him the respect of faculty, alumni, and cadets alike. His reputation was not that of a culture warrior, but of a shepherd, steady, measured, careful with words, always striving to unite rather than divide.

And yet, when the storm came, even a general found himself caught in the crossfire. Political leaders demanded action. Students demanded protection. Critics spread false claims about his loyalties. Bureaucratic processes slowed his hand, while social media accelerated outrage. The result was a presidency undone not by incompetence or corruption, but by the collision of university governance with the polarized politics of our age.

This article seeks to evaluate Welsh’s leadership with fairness and clarity: to honor his service, to acknowledge his missteps, and to consider what lessons Christian leaders might draw from his tenure and resignation.

The Broader A&M Leadership Crisis

To understand General Welsh’s resignation, it’s necessary to step back and look at the broader turbulence that has marked Texas A&M’s upper leadership in recent years. His departure did not occur in a vacuum. It followed a string of controversies that left Aggieland weary, skeptical, and watching closely every move from the top of the Administration Building.

Before Welsh, there was Kathy Banks. Appointed in 2021, her presidency was marred by the debacle surrounding the hiring of journalist Kathleen McElroy to lead the journalism program. What began as a celebrated announcement quickly unraveled into public controversy over her prior DEI statements and tenure expectations. The fallout forced A&M into the national spotlight, led to accusations of political interference, and ultimately resulted in Banks’s resignation in July 2023. The episode revealed how vulnerable the university had become to cultural and political crossfire.

Before Banks, President Michael Young’s tenure (2015–2020) ended under far less dramatic circumstances, but his resignation nonetheless marked another transition in a season of flux. Though his leadership was not consumed by cultural battles, his departure highlighted the broader instability in A&M’s executive ranks.

Layered on top of this was the appointment of Glenn Hegar as chancellor in July 2025, following John Sharp’s long service. Hegar, coming from the Texas Comptroller’s office, entered office as Welsh’s controversy was unfolding, placing him in the role of both supporter and stabilizer as the system tried to navigate yet another leadership storm.

Against this backdrop, Welsh inherited a presidency already under scrutiny. Aggies were weary of turnover. Faculty feared politicization. Politicians were emboldened to press their influence. And students, often the overlooked constituency in these clashes, were caught in the crosscurrents of shifting priorities and national narratives.

Thus, when the classroom confrontation over gender ideology surfaced, it became more than a localized dispute. It was the spark that touched tinder laid down by years of tension. Welsh’s handling of the situation, therefore, was judged not merely on its own merits but through the lens of Aggieland’s recent leadership crises.

His resignation, then, should be understood as the latest chapter in a much longer story, one in which Texas A&M, like many flagship universities, has struggled to balance academic freedom, political pressure, and cultural change while maintaining stability at the very top.

Welsh’s Leadership Strengths

General Mark Welsh came into the presidency of Texas A&M with a résumé few university leaders could match. A retired four-star general, he served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force from 2012 to 2016, overseeing more than 690,000 active-duty, Guard, Reserve, and civilian forces. His reputation was one of calm authority, steady judgment, and integrity under pressure. For Aggies, this wasn’t abstract: it was visible daily in his years as dean of the Bush School of Government and Public Service, where his personable leadership style had already earned deep respect.

1. Military heritage of integrity.

Welsh’s Air Force career instilled in him a sense of chain of command, decisiveness, and discipline that translated well to university life. He was no ivory-tower bureaucrat. Students often remarked on his approachable style, his willingness to listen, and his ability to lead without bluster. The Aggie values of respect, excellence, leadership, selfless service, and loyalty were not slogans to him; they were lived practices shaped in decades of command.

2. Student-first posture.

One of Welsh’s most consistent patterns, and a strength often overlooked, was his prioritization of students. During the controversy that engulfed his presidency, multiple students testified that he personally called them after they emailed him, ensuring they felt heard. In an era when university presidents are often caricatured as aloof fundraisers or political appointees, Welsh’s instinct was pastoral: he treated students as his flock. His farewell letter only reinforced this, thanking Aggies for giving the university “a pulse” and reminding them that respect for others is the “front door to a respected life.”

3. Collaborative leadership.

Welsh’s years at the Bush School were marked by bipartisan credibility. He created an environment where conservatives and liberals alike felt free to debate, rooted in the school’s namesake ethos of public service above partisanship. That credibility followed him into the presidency, where faculty noted his calm presence and ability to convene people from across the ideological spectrum.

4. Commitment to institutional integrity.

Even in the firestorm that cost him his position, Welsh took steps that reveal a methodical concern for governance. He convened deans, directed audits, and initiated reviews of curriculum standards. His instinct was not to capitulate to the loudest voices but to work through proper channels, a strength in principle, though one that later exposed him to charges of slowness or indecision.

In short, Welsh’s presidency was rooted in integrity, humility, and care for people. These qualities earned him the admiration of students and faculty alike, even as they proved insufficient to shield him from the storm that followed.

Welsh’s Leadership Weaknesses

For all his strengths, General Welsh’s presidency was not without vulnerabilities. In fact, the very qualities that made him respected, humility, process-mindedness, and care for students, also created weaknesses in a political and cultural moment that demanded speed, clarity, and narrative control.

1. Process opacity.

Welsh leaned heavily on Texas A&M’s internal systems: faculty governance, academic rules, and administrative audits. This instinct was commendable from a standpoint of institutional integrity, but it created the perception that he was moving too slowly or even avoiding decisive action. To outside observers, especially political leaders like Rep. Brian Harrison, it seemed as though Welsh was dragging his feet. In reality, he was following due process, but in a climate where outrage moves at the speed of social media, process alone looked like paralysis.

2. Mixed messaging.

The timeline of statements made matters worse. Early reports suggested Welsh had reassured faculty that “no one is being fired.” Days later, the professor in question was terminated. For critics, this was evidence of duplicity; for supporters, it was a sign he was caught between competing pressures. In truth, it reflected how quickly the situation evolved. Still, the inconsistency created mistrust, and once credibility is shaken in a crisis, every subsequent decision is interpreted through a lens of suspicion.

3. Narrative vacuum.

Welsh’s deliberate, understated style became a liability when Rep. Harrison released classroom recordings and phone transcripts to the public. The story quickly left A&M’s walls and entered the furnace of state politics and national culture wars. Welsh, by instinct and habit, refused to play the role of a political pugilist. He did not flood the airwaves with counter-narratives or rally public opinion. Instead, he kept his communication measured, private, and often late. That restraint, though admirable in normal times, created a vacuum into which others rushed with louder voices and harsher narratives.

4. Political fragility.

Ultimately, Welsh lacked the political cover to survive. Despite the support of many students, faculty, and even the chancellor, the cumulative pressure of legislators, activists, and public perception proved too great. His careful balancing act, respecting process, listening to students, disciplining faculty through channels, was interpreted by both sides as a weakness. To progressives, he had capitulated to political bullying; to conservatives, he had not moved quickly enough to purge ideology.

In the end, Welsh’s resignation was not the result of one fatal mistake but of a convergence of weaknesses: slow process in a fast-moving storm, mixed signals in a polarized age, and silence in a narrative war. His virtues as a leader, humility, restraint, and patience, collided with a cultural moment that rewards combativeness, clarity, and speed.

The “Obama’s DEI Guy” Smear

One of the more infuriating claims that circulated during the controversy was the label of General Welsh as “Obama’s DEI Guy.” The charge was simple but misleading: he served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force during the Obama administration; therefore, he must have been an architect of the Pentagon’s diversity, equity, and inclusion policies. From there, critics spun a narrative that painted him as a Trojan horse of progressive ideology at Texas A&M.

The reality is both more mundane and more honorable. Welsh was not a partisan appointee but a career military officer with decades of service under both Republican and Democratic presidents. He served under President Obama, yes — but also under President George W. Bush, and his tenure as Air Force Chief of Staff extended into the early months of the Trump administration. To reduce a four-star general’s career to a partisan caricature is not only inaccurate but dishonoring of his service.

What’s more, Welsh’s record at the Bush School of Government and Public Service should have dispelled such notions. He cultivated an environment where students of all political stripes, conservative, moderate, and progressive, could learn, debate, and serve together. He was known less for ideological agendas and more for his steady emphasis on service, respect, and excellence.

From a biblical perspective, the attack on Welsh illustrates the danger of false witness (Exod. 20:16). Labels can be powerful weapons, especially in our polarized environment, but they often obscure more than they reveal. To accuse a man of ideological partisanship simply because of the dates on his résumé is both careless and uncharitable. It trades truth for expedience, reducing complex realities into weaponized sound bites.

Welsh’s leadership was many things — methodical, humble, student-centered — but it was never partisan in the sense his critics claimed. The smear told us less about him and more about the cultural climate: a world where suspicion sells, truth is optional, and leaders can be caricatured overnight by the echo chambers of politics and media.

The Pressure Triangle: Bureaucracy, Politics, Critical Theory

Why did General Welsh’s presidency collapse so quickly? The answer lies not in one failure, but in the convergence of three forces — bureaucracy, politics, and cultural ideology — that pressed against him simultaneously. Each alone would have been manageable. Together, they formed a triangle of pressure that no president could withstand without extraordinary political capital.

1. Bureaucracy.

Texas A&M, like any large public university, operates through layers of process: academic rules, faculty oversight, and administrative audits. Welsh leaned into this structure. When concerns arose about classroom content, he responded by convening deans, reviewing catalog standards, and initiating procedural checks. This was entirely appropriate within the governance model of a major research institution. But bureaucracy is slow, deliberate, and inward-facing. By the time meetings were scheduled and memos circulated, the crisis had already escaped the campus and entered the public square.

2. Politics.

Enter Representative Brian Harrison. When recordings and transcripts surfaced, Harrison moved quickly, posting videos, releasing emails, and framing the issue as one of moral urgency. For him, this was not merely a local classroom matter — it was an opportunity to press influence over the state’s flagship university. Once the controversy reached the legislature, Welsh was caught in a tug-of-war he could not win. Faculty and staff looked for him to defend academic integrity. Legislators demanded decisive action and accountability. Any delay looked like weakness. Any action looked like capitulation.

3. Critical Theory.

Lurking behind both bureaucracy and politics was the deeper cultural current: critical theory and its derivatives. In this worldview, disagreement is harm, and dissent from progressive orthodoxy is reclassified as “hate speech.” That was precisely the framework at play in the classroom itself, where a professor equated a respectful student’s question with intolerable hostility. Once that framework shapes the narrative, traditional appeals to academic freedom or governance integrity sound tone-deaf. Welsh, trained in a culture of command and process, seemed ill-equipped to contest the ideological frame in public.

The result of the triangle.

Together, these forces left Welsh boxed in. His reliance on bureaucracy slowed his hand. Politics demanded speed and spectacle. Critical theory shaped the cultural lens through which every action was interpreted. The professor became a martyr to some, a villain to others. The student became a hero to some, a disruptor to others. And Welsh — the president trying to balance integrity, order, and prudence — became, in the end, expendable.

The tragedy is not that Welsh lacked integrity or care. The tragedy is that integrity and care were not enough. In a world where bureaucracy moves slowly, politics moves fast, and ideology moves hearts, the triangle of pressure closed in faster than one leader could adapt.

Biblical Leadership Lens

Evaluating President Welsh’s tenure cannot be done solely in political or procedural terms. As Christians, we must also ask: how does his leadership measure up to biblical models? Scripture gives us categories that help illuminate both his strengths and his struggles.

1. Nehemiah’s steadfastness.

When Nehemiah rebuilt Jerusalem’s wall, he faced ridicule, political sabotage, and pressure to abandon the work. His strength was focus — “I am doing a great work and cannot come down” (Neh. 6:3). Welsh demonstrated a similar spirit of integrity and steadiness. He refused to be baited into reactive statements. He worked through proper structures. He honored the process. In that sense, his posture reflected Nehemiah’s refusal to let external noise dictate his steps.

2. Pilate’s expedience.

But there is another comparison. Pilate, though personally convinced of Jesus’ innocence, yielded to the pressure of the crowd (John 19:12–16). His failure was not malice, but cowardice — the fear of man eclipsing the fear of God. Welsh’s resignation, though framed in humility and gratitude, inevitably raises the question: Was it resignation out of principle, or resignation under pressure? To many, his exit felt more like Pilate than Nehemiah, a good man worn down by forces larger than himself, yielding to political expedience rather than standing resolute to the end.

3. The shepherd’s balance.

Jesus described faithful leaders as shepherds who both protect and discipline (John 10:11–15). A shepherd defends the flock against wolves but also corrects wayward sheep. Welsh excelled at listening, protecting students, and ensuring they felt heard. Where he struggled was in drawing sharp boundaries of discipline, first with faculty whose classroom behavior crossed lines, then with politicians whose pressure overreached. His shepherding heart was evident; his shepherding staff seemed less ready at hand.

4. Proverbs’ wisdom.

Proverbs 29:25 warns, “The fear of man brings a snare, but he who trusts in Yahweh will be exalted.” Welsh’s leadership at its best reflected a man anchored in principle, slow to anger, and careful with words. But the snare of man’s approval — from faculty, from politicians, from students — hung constantly around his neck. In a polarized age, no leader can satisfy all constituencies, and Welsh’s attempts at balance left him vulnerable to attack from every side.

In biblical terms, then, Welsh was not a failed leader but a tested one. His example warns us that integrity and humility, while essential, must be paired with courage and clarity. The Nehemiah posture of steadfast focus must win out over the Pilate temptation of expedience. Only then can shepherds lead God’s people faithfully amid cultural storms.

Integration with Previous Articles

This article does not stand alone. It belongs within the broader arc of reflection that has shaped the Tested series. Each prior installment wrestled with a dimension of the same conflict — cultural upheaval, institutional strain, and the call to integrity in leadership. Welsh’s story brings those threads together.

In that piece, I argued that the battle at Texas A&M was not just about curriculum but about the very spirit of Aggieland. Would the university stand by its core values, or yield to the spirit of the age? Welsh’s resignation makes that question more urgent, not less. The spirit of Aggieland was visible in the farewell crowd singing The Spirit of Aggieland as Welsh descended the steps. Yet the spirit tested remains: will the next generation of leaders hold fast to truth when the winds blow stronger still?

That essay reflected on the difficulty of maintaining credibility when words and actions appear to diverge. Welsh’s presidency embodied that tension. His reassurances that “no one would be fired” were overtaken by later decisions to dismiss faculty. His process-driven patience was read as weakness. The test of integrity in leadership is not only doing the right thing, but being perceived as doing it — and in that crucible, Welsh bore scars.

Here, I argued that even conservatives can fall into the trap of using critical theory’s categories of harm and power. Welsh was squeezed by both sides of this phenomenon: progressives who weaponized “hate speech” to silence dissent, and conservatives who demanded immediate firings to prove ideological loyalty. In both cases, truth was secondary to optics. Welsh became the casualty of cancel culture from two directions at once.

Finally, I wrote that true academic freedom is anchored in truth, not ideology. Welsh’s presidency exposed how fragile that freedom has become. Professors claimed the right to insert ideology into children’s literature. Politicians claimed the right to dictate faculty dismissals. Welsh’s attempt to uphold institutional governance faltered under these competing claims, but the principle remains: without truth, academic freedom collapses into propaganda or politics.

Together, these four earlier reflections set the stage for this one. Welsh’s resignation was not an isolated failure but the convergence of every test described: spirit, integrity, cancel culture, and academic freedom.

Lessons for Christian Leaders

General Welsh’s resignation is more than a university story; it’s a leadership parable. Christian leaders today — whether in churches, ministries, nonprofits, or public service — can glean several lessons from his tenure and departure.

1. Process must be paired with courage.

Welsh modeled the importance of process, honoring institutional integrity and resisting the temptation to bypass governance. That instinct was right. But process without courage falters under pressure. Leaders must not only “do things the right way” but also project the courage to stand publicly for truth, even when misunderstood.

2. Communication clarity is leadership armor.

Crises thrive in the absence of clear communication. Welsh’s measured style left room for others to control the narrative. For Christian leaders, silence in the face of controversy is rarely neutral. In a world of fast-moving information, leaders must tell their story before others tell it for them. Paul’s letters to the early churches are a model here: transparent, timely, clarifying, always pointing back to truth.

3. Shepherding requires both compassion and discipline.

Welsh excelled at listening to students, but hesitated to draw firm boundaries with faculty or politicians. Shepherds must both protect and correct (John 10:11–15). To protect one part of the flock while neglecting another leaves all vulnerable. Biblical leadership calls for tenderness and toughness in equal measure.

4. Fear of man vs. fear of God.

Proverbs 29:25 warns that the fear of man is a snare. Welsh’s resignation, though dignified, illustrates the cost of yielding to external pressure. For Christian leaders, the challenge is to trust God’s sovereignty, not political winds. Faithfulness, not success, is the true measure — a truth Chuck Colson lived by and Welsh’s own farewell letter hinted at.

5. Faith over expedience.

The temptation of every leader is to calculate outcomes and protect position. Yet Scripture reminds us: “It is required of stewards that they be found faithful” (1 Cor. 4:2). Welsh’s story challenges us to resist expedience and embrace fidelity — to God, to truth, and to those we serve.

In sum, Welsh’s presidency teaches us that integrity and humility, though essential, are not enough. Leaders must also cultivate courage, clarity, and conviction. For those walking in Christ, these qualities flow not from self-preservation but from the Spirit’s power, enabling us to stand when others fall.

Farewell & Legacy

So, as I watched General Welsh and his wife walk down the stairs of the Administration Building, with applause and cheers echoing from thousands of students, faculty, and staff, I couldn’t help but think about the road that led here. It was a profoundly Aggie moment — spontaneous, heartfelt, steeped in tradition. Honestly, I was almost brought to tears when the crowd, softly but passionately, began to sing The Spirit of Aggieland. That song, which Aggies know by heart, became a benediction for a man who had served his nation and his university with dignity.

The farewell letter Welsh released earlier that day reflected the same humility he carried throughout his career. He thanked chancellors, regents, faculty, staff, and above all, students. “You make this university whole,” he wrote, “you give it a pulse.” He called Texas A&M “a shining city on a hill,” a place that welcomed his family, shaped his children, and inspired him daily. There was no bitterness in those words, no attempt to rewrite the controversy. Only gratitude, affection, and reverence for a university he clearly loved.

That is how many will remember him. Not as a coward undone by politics, nor as a villain guilty of ideological betrayal, but as a servant-leader who gave his best in an impossible climate. Welsh’s resignation was forced by circumstances larger than any one man — bureaucracy slow to act, politics quick to pounce, and cultural battles impossible to escape. Yet he chose to leave with grace, not rancor.

For Aggieland, his exit is both a loss and a legacy. It is a loss because yet another president departs amid controversy, deepening the sense of instability at the top. But it is legacy because his manner of departure, hand in hand with his wife, cheered by students, singing the Spirit of Aggieland, left an indelible image of leadership marked by humility and respect.

For Christians, Welsh’s farewell offers a final lesson. Hebrews 13:7 exhorts us: “Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God. Consider the outcome of their way of life, and imitate their faith.” Welsh’s outcome was not triumph in the worldly sense, but testimony in the spiritual sense: a reminder that faithfulness, gratitude, and humility matter more than victory in the culture wars.

In the end, Welsh will not be remembered as “Obama’s DEI guy” or as a pawn in partisan games. He will be remembered as an Aggie, a general, a dean, a president, and above all, a man who loved his students and served his university with honor. That is a legacy worth cherishing.